Spock : “… I have noted that the healthy release of emotion is frequently very unhealthy for those closest to you.”

Star Trek, “Plato’s Stepchildren” (s3ep10), Stardate 5784.2

Meditation, specifically mindfulness meditation, is touted as a stress-relief exercise. Busy people believe that if they can block out the time to meditate for X minutes a day, or when stressed, this will make more happy and productive. It has been all the rage in Silicon Valley too.

But it doesn’t work.

It will calm your mind while you are sitting, but as soon as you are back to work, your blood pressure will quickly rise again. Old habits will quickly resurface. Self-help, in short, does not help.

How do I know this?

I tried the same trick in my late 20’s. My first child was born, and I was working at Amazon (yes, that Amazon) for a few years in a technical support role. The environment was stressful, demanding, constantly on the move, the on-call rotation gave little time to decompress because something was always broken,1 and I had to drive into work at all hours of the night to try and fix it.

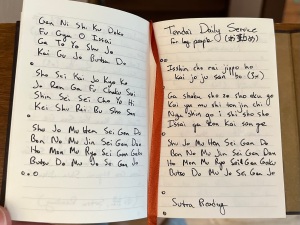

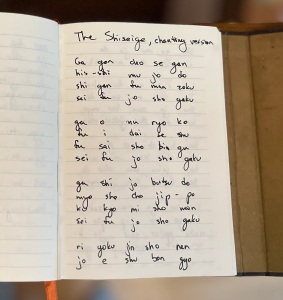

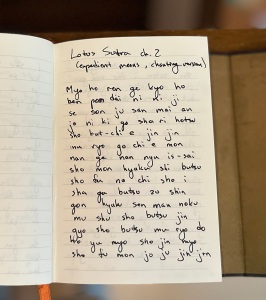

Since I had recently converted to Buddhism at the time, and listened to a lot of Ajahn Brahm dharma talks, I wanted to try meditation. We had a spare office that no one used, so I would go in there once or twice a day, turn off the lights, dutifully sit, chant certain Buddhist mantras, meditate for 20 minutes or more, and then return to work.

As soon as I was back at my desk, the stress would rise all over again. I kept at the meditation for months, almost a year, before I finally gave up.

The stress, constant sense of inadequacy measuring myself to hyper-competitive co-workers who graduated from Stanford, unrealistic work performance goals, fear of losing my job, and so on simply didn’t go away until I QUIT MY JOB AND TOOK A LESS DEMANDING ONE.2

It took me years as a Buddhist to finally realize that stress-relief is not what mindfulness meditation was intended for.

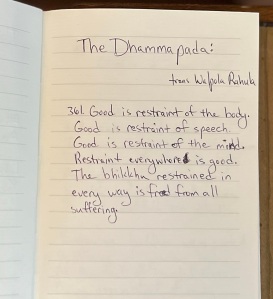

Mindfulness meditation is a tool to develop insight, not stress relief. It is necessary in the early stages of meditation to quiet the chatter in the mind, but that is just the first stage. It is to remove barriers to insight by develop a focused mind, and a quiet mind, a mind that can perceive things in a more balanced way. Consider this quote from the Buddha in a very early text, the Dhammapada:

Translation by Soma Thera from https://www.accesstoinsight.org/tipitaka/kn/dhp/dhp.25.budd.html

- There is no meditative concentration for him who lacks insight, and no insight for him who lacks meditative concentration. He in whom are found both meditative concentration and insight, indeed, is close to Nibbana.

- The monk who has retired to a solitary abode and calmed his mind, who comprehends the Dhamma with insight, in him there arises a delight that transcends all human delights.

…- Control of the senses, contentment, restraint according to the code of monastic discipline — these form the basis of holy life here for the wise monk.

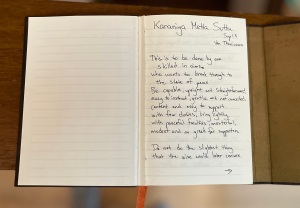

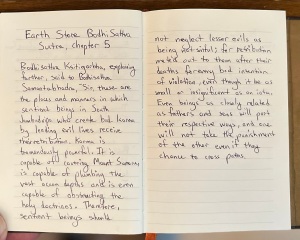

The emphasis is on focus, insight, and contemplation NOT relaxation or stress-relief. Mindfulness meditation has been repackaged and sold to naive Westerners with false promises. Meditation really does provide excellent benefits, but it has to be done as part of a much larger, holistic lifestyle change and with wholesome intentions. This is the “holy life” as described by the Buddha: a life of wholesome, guilt-free conduct, goodwill towards others, and a desire to pursue the Dharma (the teachings of the Buddha).

First, one should take up the Five Precepts of Buddhism. As we see in verse 374 above, the Buddha openly encourages that we curb our worst behaviors first as a foundation for other Buddhist practice. One will gain no lasting benefit from meditation until this is done. Full stop.

Second, one must approach meditation with the mindset of a monk. It is not necessary for lay-people to give up everything and go live in the woods. Buddhism accommodates both the “house-holder” lifestyle and that of a true renunciant (a.k.a. a monk or nun). But both the renunciant and the house-holder are expected to live a life of moderation and restraint.3 Easier said than done (speaking as a gamer and foodie), but it’s a goal to sincerely aspire to.

Speaking of restraint, one should always guard one’s speech. A long time ago, a Buddhist minister I admired once told me that speech was like toothpaste: once it was out of the tube, you couldn’t put it back. One has to learn to carefully monitor what one says both in person and online (and yes, at work). Again, easier said than done, but the alternative will only make your life miserable.

Finally, when such good foundations are established, meditation will help you learn more about yourself, and the world around you.4 It’s incredibly helpful, and life-changing when carried to fruition. I have my own little private insights that have stayed with me through the years, and I hope you will find yours too.

Namu Amida Butsu

Namu Shakamuni Butsu

P.S. if you feel the need to calm yourself right away, try something much simpler. You can recite the nembutsu, the Heart Sutra, a mantra, whatever. Try that for a minute, and see if that works. It is a band-aid fix though, and you still need to approach things from a holisitic standpoint, or you will gain no long-term benefit. Alternatively, just go for a walk.

1 Years later, the sound of a pager going off still triggers me a little bit. No joke.

2 Another ex-Amazonian who had joined the same company years earlier confided in me that after leaving Amazon, he drank himself stupid for months to decompress. I noticed that I was still on a hair-trigger for months after leaving Amazon, and it took me a while to unlearn those habits too. My wife noted that my posture improved after leaving, and that I grumbled about work less. Some jobs are simply not worth staying in.

3 The Buddha was pretty flexible about what exactly this meant, citing whatever cultural standards applied at the time as a benchmark. In short, a lot of it is rooted in common courtesy and good sense. If you cannot act toward others using common courtesy, meditation ain’t gonna fix your issue.

4 You may learn that your whole problem is that your job sucks, for example, and that the burn-out is not worth the money. Of course, if you’re a single mom caring for three kids, you have a lot fewer options available to you, and in such cases I recommend the nembutsu as a starting point.

You must be logged in to post a comment.