I alluded in recent posts about my visits to the temple of Sanjūsangendō (三十三間堂, San-ju-san-gen-do) in Kyoto, Japan, but I’ve never really talked about it.

My experiences with Sanjusangendo go all the way back to our first trip to Japan together in 2005. My wife (whose Japanese) and I had married the previous year,1 and we came to Japan to meet the extended family, but also take in many sites. That first trip through Kyoto was a whirlwind, and I have very fuzzy memories of most of it. I couldn’t remember much about Sanjusangendo, and since we couldn’t take photos, I had very little to remind me either.

And yet, something about Sanjusangendo drew us back in recent years. My late mother-in-law really liked Sanjusangendo, and my wife wanted visit again for her mother’s sake, and now with 20 years of experience in Buddhism, the temple made a lot more sense to me. The fact that it’s a Tendai temple (and I like Tendai Buddhism) was icing on the cake. My wife was really inspired by it too, so the following year we visited it again.

…. so, what is Sanjusangendo?

Sanjusangendo is a Buddhist temple, which venerates the bodhisattva Kannon, also known as Avalokiteshvara, Guan-yin, etc. It was founded in the 12th century by the infamous warlord Taira no Kiyomori as a way to impress Emperor Go-Shirakawa (tl;dr it didn’t work). What makes Sanjusangendo so famous is two things:

- It’s very long, narrow main hall (本堂, hondō). This is different than most temples which have a more square-shaped main hall. The hondō of Sanjusangendo is a very long rectangle, but there’s a reason for this. The featured photo above is something I took in 2023, and shows the scale of the building. The website also has a nice photo.

- The temple’s main attraction is the 1,000 statues of Kannon bodhisattva, centering around a much larger statue of Kannon. These statues are lined up in rows along the main hall, and in front of them are other statues featuring various gods and other divine beings protecting the temple. More on that below.

Since Sanjusangendo doesn’t allow photography inside the main hall,2 you should check out the official website instead. You can see the main hall, and the row upon row of Kannons here. The official website also has photos of each figure.

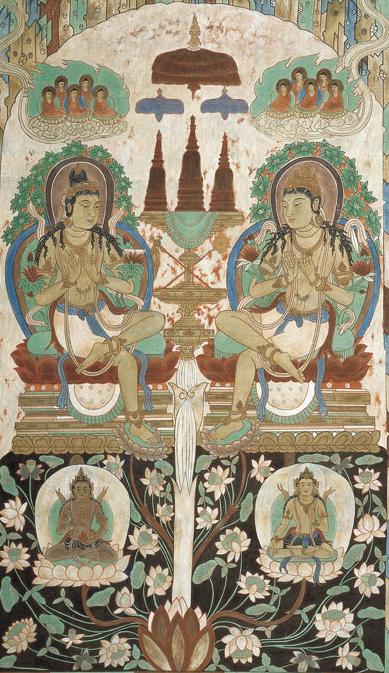

The main figure of devotion, as i said above, is the bodhisattva Kannon, but since Kannon has many forms, this form is the 1,000-armed Kannon called Senju Kannon (千手観音). This form of Kannon isn’t limited to Japanese Buddhism; I have seen this form expressed at Vietnamese Buddhist temples as well. The idea is that Kannon, according to the Lotus Sutra, uses many different means and methods to help people, and the 1,000 arms, each holding different objects, symbolizes the diverse ways that Kannon helps others.

You can see a photo of the 1,000-armed Kannon here.

Something you might also note is that the Kannon statue has 11 heads. Just as the 1,000 arms show Kannon’s efforts to help all beings in a variety of ways, the 11 heads show Kannon’s vigilance in watching out over people.

Not shown in the photos is a small display which teaches a particular mantra associated with the 1,000-armed Kannon:

| Language | Mantra Pronunciation |

|---|---|

| Sanskrit | Oṃ vajra-dharma hrīḥ svāhā |

| Japanese, katakana script3 | オン サラバ ダルマ キリ ソワカ |

| Romaji | On saraba daruma kiri sowaka |

You can recite this mantra in Japanese or Sanskrit. I am unclear what the translation is, but I’ve been told before that translating mantras is kind of pointless, like giving answers to a Zen koan. So, I left out the translation.

Anyhow, flanking the great big statue of Kannon on either side are 10 rows of smaller, standing statues of Kannon, each with 1,000 arms, which you can see here. The website says that of the one-thousand statues, they were built over time: 124 were from the late Heian period (12th century) and the rest were constructed during the Kamakura period (13th-15th century). There are a total of 1,000 statues, each one slightly different, but generally the same form.

Finally, in front of these statues is a series of mythical figures. Some are originally from India, and traveled the Silk Road, gradually transforming into what we see today. Others are more native Japanese deities who’ve also become Buddhist guardians. You can see the full catalog here.

To give an example of the eclectic nature of these figures, one figure is a Buddhist guardian deity named Vajrapani (Naraenkengō 那羅延堅固 in Japanese), whose imagery was influenced by the Greek hero Herakles at a time when places like Bactria and Gandhara were still part of the Greek world.

On the other hand, you can also see the famous figures of Raijin and Fūjin who are Thunder and Wind gods respectively. As far as I know, these are native deities and did not originate from the Silk Road.

The quality of the artwork is really excellent. When you see any of these figures, Kannon, Vajrapani, Raijin, etc, the life-like quality is really impressive. And, like many examples of Buddhist art, they are full of symbolism and visual meaning beyond words. They impress and inspire those who see them. Since I have now seen Sanjusangendo three times, I found that it continues to impress me every time I see it.

Speaking from experience, Sanjusangendo is a place that requires some context to really appreciate. If you are unfamiliar with Kannon and why they have one-thousand arms, or with the strange but beautiful figures guarding the front row, then some of it will feel like a mystery. It’s a beautiful mystery, but still a mystery. But, hopefully after reading this, you will get a chance to see it someday and really get a feel for why this place is special.

As someone who has an affinity for Kannon since I first became a Buddhist, it is a special place for me. 😊

Edit: fixed a number of typos. Three-day weekend drowsiness. 😅

P.S. Again, apologies for the lack of photos. I know sometimes foreigners will take photos anyway (I have seen people do this), despite the signs clearly saying “photography prohibited”, but I don’t want to be one of those tourists. So, if you want to see more, check out the excellent website.

1 Twenty-year anniversary as of early 2024. 🎉

2 A lot of temples in Japan do this. I don’t fully understand why, and it is frankly a little frustrating.

3 Katakana script is often used to write foreign-imported words in Japanese, as opposed to hiragana script. Since mantras are originally derived from Sanskrit, using katakana makes sense in this context. Sometimes katakana is also used for visual impact (like in manga), so that might explain things too. NHK has a nice website explaining how to read katakana.

You must be logged in to post a comment.