Hello Everyone,

I recently finished two related books this week: the Xuan-zang book I wrote about before and a new book by Richard Foltz titled Religions of the Silk Road: Premodern Patterns of Globalization. The latter book was fairly short, but it was well-written and I finished it in about 4 days. I highly recommend it.

One of the reasons why I enjoyed these books so much is that they helped explain an important question about Buddhist history: how did Buddhism go from India to China?

Anyone who’s studied a little history about Buddhism knows it travelled the Silk Road from India to China, where it flourished and influenced other East Asian countries (Korea, Japan, Vietnam, etc). But this glosses over a lot. So these two books helped explain what exactly happened, and historical research was actually kind of surprising.

Different kingdoms and people “ruled” the Silk Road at different points of time, but many of them had a common “Iranian” origin. This is not the same as the modern country of Iran, but rather a common ancestry, which included such people as the Persians, the Sogdians, the Parthians and the Indo-Aryans such as Siddhartha Gautama. They had a common ancestry, spoke related Iranian-languages, and had common religious traditions that helped influence the new religions they encountered.1

What Is the Silk Road?

The Silk Road was actually a network of trade routes that connected China with India, Persia and beyond Persia to the Near East. There were multiple routes, not a single road, and it was not common for a single merchant to travel the entire length. Instead, merchants would often use a “relay system” to bring goods to a major city along the road and trade there. The same goods might be carried by another merchant elsewhere, and so on.

For example, between Indian and China there were three major roads, two passing through Central Asia: the “north” road which was longer but somewhat safer and passed north of the Taklamakan Desert, and the shorter “southern” road which was quicker but was riskier due to mountains, flooding rivers and the Desert. Xuan-zang, in his famous journey, took the northern route from China to India, and was relatively safe, but on his return, he took the southern route and nearly drowned twice, lost his elephant and many important items he brought back from India. Meanwhile, in the ancient city of Palmyra in Syria, mummies have been found wrapped in Chinese silk.

Anyhow, the constant trade back and forth also brought other people who were not in business. Monks, priests and people seeking their fortune would sometimes accompany merchant caravans. Cities and kingdoms on the Road often welcomed such people because they helped connect them with important cultures like Persia, India and China, and would help improve their prestige. With greater prestige and culture, such a kingdom might prosper over rivals.

Why Did Buddhism Spread Along the Silk Road?

The original reason was probably trade. Rulers along the Silk Road would patronize traveling monks by building monasteries and establishing new Buddhist communities. This would help generate donations for the local economy, and enhance the culture and prestige of the city helping the economy further. For example, at the city of Balkh (now Afghanistan), Xuan-zang found 100 monasteries and a 3000 monks there in the 7th Century.

In reality, the local population probably didn’t convert to Buddhism en masse, but instead it may have blended with existing religious traditions. Further, as Buddhism declined, later religions such as Nestorian Christianity, Manichaeism and Islam spread the same way. It was a recurring pattern: whoever controlled the trade influenced the religious tendencies of the region.

What Kind of Buddhism Did They Spread

Three schools of Buddhism, out of the original 18, that spread along the Silk Road were:

- Mahasangikas – Who tended to downplay the importance of the enlightened arhats, and emphasize intuition. They helped build the famous giant statues at Bamiyan, now destroyed.

- Dharmaguptakas – Who elevated the importance of the Buddha, such that only he was worthy of offerings, and not the monks. They were the most important school early on, but gradually declined. The Agama Sutta in the Chinese Canon (equivalent to the Pali Canon in Theravada) is partly from Dharmaguptaka sources, as well as the Chinese monastic code of discipline.

- Sarvastivadins – Who believed that past, present and future all existed simultaneously and were thus considered heretical according to the 3rd Council of Buddhism. Otherwise they were similar to other schools. Much of the Agama Sutta above derives from Sarvastivadin sources as well.

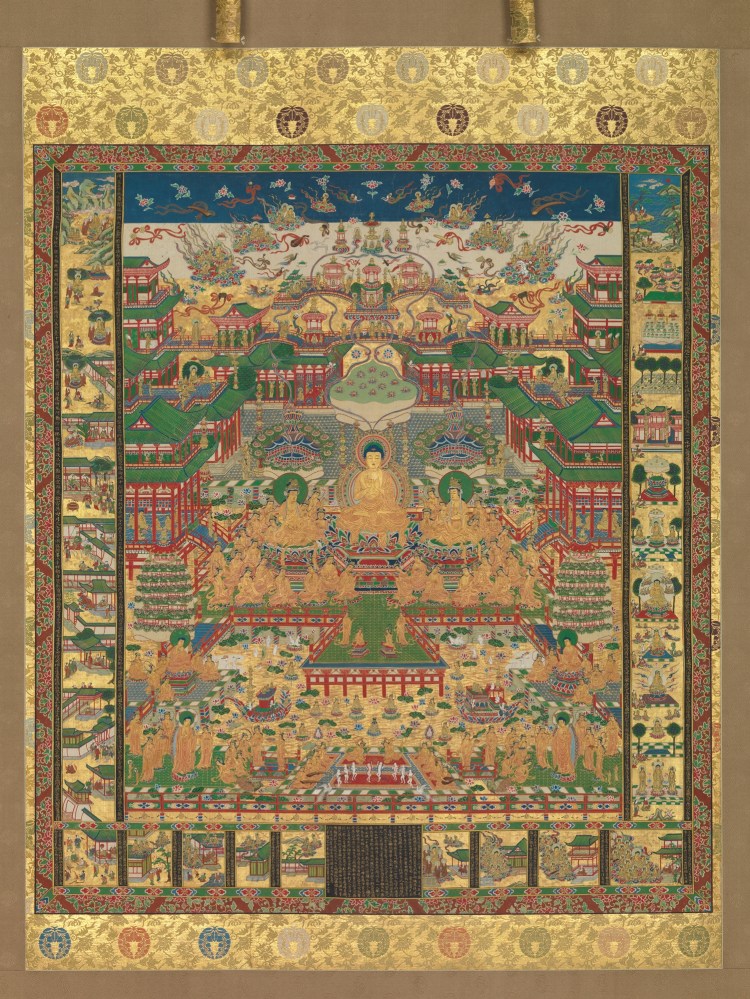

Finally of course was Mahayana Buddhism, which is what we see now in East Asian Buddhism. Mahayana Buddhism was not a distinct school at this time, but had members from each of the various Indian schools, interacted closely with them, and was thus influenced by them. Mahayana Buddhism and its “bodhisattva practices” was a kind of extra-curricular activity monks and nuns could participate in, on top of their usual monastic discipline.

Research shows that much of imagery and sutras used in Mahayana Buddhism may have been composed outside of India in Central Asia. Iranian culture already had a diverse pool of beliefs and imagery, including but not limited to Zoroastrianism, and this may have helped shape what we now know as East Asian Buddhism. More on that in another post.

Who Spread Buddhism?

There were four major peoples that help spread Buddhism along the Silk Road, three of whom were ethnically Iranian:

- The Bactrians, who blended Indian Buddhism with Greek culture.

- The Kushans, who learned form Bactrians and spread it further.

- The Sogdians, master traders and translators

- The Parthians, the last and most powerful group who brought many texts and translators to China.

Buddhism began to spread from India to the Greco-Iranian kingdom of Bactria first. It was close to Kashmir, which was a major center of Buddhist learning, and the Bactrian kings were tolerant of all religious traditions. The people and language were a mix of Greek setters, Indian and Bactrian (Iranian). The Bactrian language even used Greek letters. As an example of diversity and tolerance, King Menandros patronized Buddhism, though he was not a follower. His dialogues are preserved in a Buddhist text called the Questions of King Menander.

But the Bactrian kingdom didn’t last long, and was soon conquered by an Iranian people called the Sakas, then the Kushans. The Kushans are possibly a mixed-ethnic group (Iranian and Tocharian) who revived the Greco-Bactrian culture and helped spread Buddhism further than before. It was under the Kushan Empire that Buddhist statues, which resembled Greek statues in some ways, began to appear. This is the “Gandhara-style” of Buddhist art, named after a famous region of the Kushan Empire.

King Kanishka of the Kushan Empire, was considered a great patron of Buddhism, though he wasn’t a follower (he patronized Greek gods and Hindu deities as well). He organized a new Buddhist council in Kashmir to rewrite old Buddhist texts from obscure local “Prakrit” dialects into more standard Sanskrit, for example. Kanishka also helped build monasteries and communities throughout his empire. He is often called the “Second King Ashoka” for this reason.

But the group that helped spread Buddhism the most wasn’t the Kushans, it was the Sogdians. The Sogdians were a small Iranian people who lived around modern Uzbekistan and Tajikistan, and were master translators and traders.

Their location along the Silk Road meant that they interacted with many different cultures, and thus they were able to carry ideas and goods to other major cultures easily. After Buddhism, the Sogdians helped spread other religions such as Nestorian Christianity and Manichaeism as well as Islam. The Sogdians frequently translated texts from one language to another: for example Prakrit to Bactrian, Aramaic to Turkish, Parthian to Chinese, etc. Ironically the Sogdians did not translate much Buddhist texts into their own language until much later (mainly from Chinese) and this may help explain why Buddhism didn’t take root in Sogdian culture. There were definitely examples of devout Sogdian monks and communities but not wide-scale devotion.

Finally, the last major group to bring Buddhism to China were the Parthians. The Parthians were another major Iranian group that eventually conquered the Kushans and establaished the Parthian Empire. it was during this time that Buddhism probably spread the furthest into Central Asia. For example in the famous city of Merv (now in Turkmenistan), researchers have found extensive Buddhist texts from the 1st-5th centuries and Buddhist communities in Shash (modern Tashkent) show that Buddhism had spread northwest of India before it turned east toward China.

The Parthians also contributed many famous translators into Chinese.2 The most famous was An Shigao (安世高) who translated a lot of basic Buddhists texts along with his student An Xuan (安玄). The surname ān (安) was frequently used for Parthians at the time. Some of these texts are still used in the East-Asian (and Western) Buddhist canon.

Why Did Buddhism Decline on the Silk Road?

As mentioned earlier, whoever controlled the trade of the Silk Road influenced religion there. After Buddhism was established, newer religions such as Nestorian Christianity and Manichaeism gradually dominated. The Persian merchants patronized both religions, as well as the state religion of Zoroastrianism and soon the Silk Road became very religiously diverse.

The final religion to appear was Islam. By the time that Islam reached Central Asia, Arab traders dominated the trade, and local kings and merchants found it advantageous to convert in order to build closer ties. In the countryside and the remote steppes, people tended to follow Nestorian Christianity and Buddhism for much longer, but in the cities, Islam and Arab culture were the new rising star and people tended to convert. Buddhism was already declining in India, so there wasn’t much incentive to maintain cultural ties with the Buddhist world. People simply lost interest.

Foltz’s book shows how the history of “Islamic conquest” at this time was often greatly exaggerated too. Writings at the time depicting local kings and warlords conquering other lands in the name of Islam were often a cover to simply expand control of trade, not religion. Research shows that the “convert or die” policies of these kings were often unsuccessful and limited in scope. What actually persuaded Central Asian people to convert to Islam were oftentimes charismatic Sufi preachers who helped fulfill the role of “shaman” that previous religions had done generations earlier. To this day, Islam in Central Asia is often syncretic and blends elements of earlier religions with canonical Islam. Meanwhile, the Nestorian Church ironically survived in the heart of the Islamic world in the form of the Syriac Church in northern Iraq and other places.

Between the change in economy, decline of Buddhism in India and role Sufi preachers played in spreading the new dynamic faith, Buddhism naturally declined and faded entirely as did Nestorianism and Manichaeism.

Conclusion

The Iranian peoples of Central Asia were critical to bringing Buddhism out of India to Central Asia, China and now the modern world. We wouldn’t have things like Zen and Pure Land Buddhism if it weren’t for the Sogdians, Kushans and Parthians among others. Ironically many of these cultures no longer exist, yet their legacy lives on in many others.

The books mentioned at the beginning of this post were a lot of fun to read and I can’t recommend them enough for those interested in Buddhist history.

P.S. another blog repost, but with many fixed and updated links.

1 Even the modern Islamic Republic of Iran is just the latest in a very long series of dynasties and rulers that stretches back to the earliest civilizations of Man. See for example the Safavid Dynasty and Achaemenid Dynasty.

2 Other famous translators were not Parthian though: Lokaksema was Kushan while Kumarajiva had ancestry from both Kashmir and Kucha, another major Buddhist center at the time.

You must be logged in to post a comment.