The Lotus Sutra, one of the most important sutras of Mahayana Buddhism, is the size of an epic novel, and thus much too large to recite cover to cover. Even reciting a single chapter can be daunting because each chapter contains a large narrative section, and one or more verse sections that recap the narrative.

For this reason, certain verse sections have become popular for chanting because they get to the heart of the Lotus Sutra and convey its essential teachings, in a manageable size.

Popular examples (among others) include the Kannon Sutra, the verse section of chapter 16, and the opening section of chapter 2. Both are actively recited in Nichiren and Tendai sect home services. Today we will focus on the big verse section at the end of chapter 16, called the jigagé (自我偈) in Japanese.

Chapter 16 of the Lotus Sutra is the big reveal of the sutra: Shakyamuni Buddha is not just a historical figure that lived in 5th century India, and member of the warrior-caste Shakya clan, but is also, on another level, a timeless Buddha that has pretty much existed since a remote, incalculable past:

Since I attained Buddhahood the number of kalpas [aeons] that have passed is an immeasurable hundreds, thousands, ten thousands, millions, trillions, asamkhyas [in other words, a mind-boggling amount of time]. Constantly I have preached the Law [a.k.a. the Dharma], teaching, converting countless millions of living beings, causing them to enter the Buddha way, all this for immeasurable kalpas.

Translation by Burton Watson

I believe this part of an important theme not just in the Lotus Sutra but Mahayana Buddhism in general: the Dharma is a timeless, eternal law of reality and the various Buddhas simply embody it. The Dharma is what matters, not one particular Buddha or another. You can see hints of this in older Buddhist sutras such as the Vakkali Sutta (SN 22.87) in the Pali Canon, but I believe that Mahayana Buddhism took it to its logical conclusion.

Later in the same verse section is the famous lines:

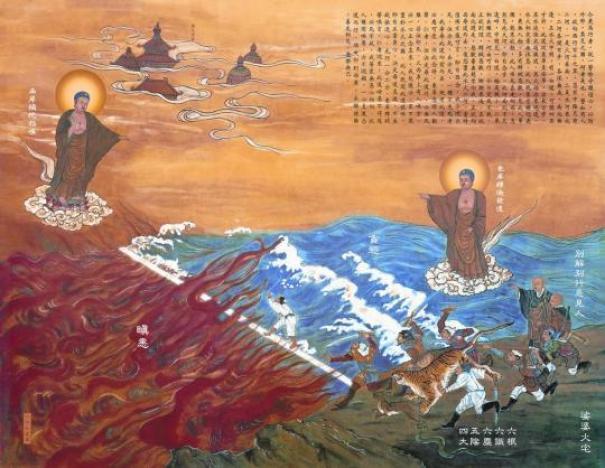

My pure land is not destroyed, yet the multitude see it as consumed in fire, with anxiety, fear and other sufferings filling it everywhere….But those who practice meritorious ways, who are gentle, peaceful, honest and upright, all of them will see me here in person, preaching the Law [a.k.a. The Dharma]

Translation by Burton Watson

To me, this reinforces that even in the worst, most desolate times, the Dharma is always there, and anyone who seeks it sincerely will find it even when others cannot see it. I’ve talked about this passage often in the Nirvana Day posts I’ve made in the past, among other places.

Anyhow, let’s move on now to the liturgy itself.

Liturgical Language

Because this is a chant used in Japanese Nichiren and Tendai traditions, among others, I am posting it as-is in Japanese, more specifically Sino-Japanese: the original Classical Chinese that it was recorded in, but with historical Japanese pronunciation. You are welcome to recite in English, or any other language, there is no restriction.

For this liturgical text, I relied on a few sources, plus I double-checked the spellings using physical sutra books I have at home. I am fairly certain it’s accurate.

Also, I formatted the text similar to how it is formatted in real service books.

Translation

I decided not to post the translation side-by-side with the text, the way I do with the Heart Sutra and such. This is due to formatting reasons on the blog, plus also length of the text makes this more difficult. I may revise this later.

For now, I highly recommend checking out a modern translation here by the excellent Dr Burton Watson. The Buddhist Text Translation Society also has an excellent translation here. The chant below is the first narrative section that goes all the way to the first verse section.

Disclaimer and Legal Info

I hereby release this into the public domain. Please use it as you see fit, but if you attribute it to this site, greatly appreciated. Also, please bear in mind this is an amateur work, and should not be taken too seriously.

Dedication

I dedicate this effort to all sentient beings everywhere. May all beings be well, and may they all attain perfect peace.

Namu Shakamuni Buddha

The Lotus Sutra sixteenth chapter, verse section

Preamble

| Classical Chinese | Japanese Romanization |

|---|---|

| 妙法蓮華経 如来寿量品 第十六 | Myo ho ren ge kyo nyo rai ju ryo hon dai ju roku |

Verse Section

| Classical Chinese | Japanese Romanization |

|---|---|

| 自我得仏来 所経諸劫数 無量百千万 億載阿僧祇 | Ji ga toku butsu rai sho kyo sho kos-shu mu ryo hyaku sen man oku sai a so gi |

| 常説法教化 無数億衆生 令入於仏道 爾来無量劫 | jo sep-po kyo ke mu shu oku shu jo ryo nyu o butsu do ni rai mu ryo ko |

| 為度衆生故 方便現涅槃 而実不滅度 常住此説法 | i do shu jo ko ho ben gen ne han ni jitsu fu metsu do jo ju shi sep-po |

| 我常住於此 以諸神通力 令顛倒衆生 雖近而不見 | ga jo ju o shi i sho jin zu riki ryo ten do shu jo sui gon ni fu ken |

| 衆見我滅度 広供養舎利 咸皆懐恋慕 而生渇仰心 | shu ken ga metsu do ko ku yo sha ri gen kai e ren bo ni sho katsu go shin |

| 衆生既信伏 質直意柔軟 一心欲見仏 不自惜身命 | shu jo ki shin buku shichi jiki i nyu nan is-shin yoku ken butsu fu ji shaku shin myo |

| 時我及衆僧 倶出霊鷲山 我時語衆生 常在此不滅 | ji ga gyu shu so ku shutsu ryo ju sen ga ji go shu jo jo zai shi fu metsu |

| 以方便力故 現有滅不滅 余国有衆生 恭敬信楽者 | i ho ben riki ko gen u metsu fu metsu yo koku u shu jo ku gyo shin gyo sha |

| 我復於彼中 為説無上法 汝等不聞此 但謂我滅度 | ga bu o hi chu i setsu mu jo ho nyo to fu mon shi tan ni ga metsu do |

| 我見諸衆生 没在於苦海 故不為現身 令其生渇仰 | ga ken sho shu jo motsu zai o ku kai ko fu i gen shin ryo go sho katsu go |

| 因其心恋慕 乃出為説法 神通力如是 於阿僧祇劫 | in go shin ren bo nai shitsu i sep-po jin zu riki nyo ze o a so gi ko |

| 常在霊鷲山 及余諸住処 衆生見劫尽 大火所焼時 | jo zai ryo ju sen gyu yo sho ju sho shu jo ken ko jin dai ka sho sho ji |

| 我此土安穏 天人常充満 園林諸堂閣 種種宝荘厳 | ga shi do an non ten nin jo ju man on rin sho do kaku shu ju ho sho gon |

| 宝樹多花果 衆生所遊楽 諸天撃天鼓 常作衆伎楽 | ho ju ta ke ka shu jo sho yu raku sho ten kyaku ten ku jo sa shu gi gaku |

| 雨曼陀羅華 散仏及大衆 我浄土不毀 而衆見焼尽 | u man da ra ke san butsu gyu dai shu ga jo do fu ki ni shu ken sho jin |

| 憂怖諸苦悩 如是悉充満 是諸罪衆生 以悪業因縁 | u fu sho ku no nyo ze shitsu ju man ze sho zai shu jo i aku go in nen |

| 過阿僧祇劫 不聞三宝名 諸有修功徳 柔和質直者 | ka a so gi ko fu mon san bo myo sho u shu ku doku nyu wa shichi jiki sha |

| 則皆見我身 在此而説法 或時為此衆 説仏寿無量 | sok-kai ken ga shin zai shi ni sep-po waku ji i shi shu setsu butsu ju mu ryo |

| 久乃見仏者 為説仏難値 我智力如是 慧光照無量 | ku nai ken bus-sha i setsu butsu nan chi ga chi riki nyo ze e ko sho mu ryo |

| 寿命無数劫 久修業所得 汝等有智者 勿於此生疑 | ju myo mu shu ko ku shu go sho toku nyo to u chi sha mot-to shi sho gi |

| 当断令永尽 仏語実不虚 如医善方便 為治狂子故 | to dan ryo yo jin butsu go jip-pu ko nyo i zen ho ben i ji o shi ko |

| 実在而言死 無能説虚妄 我亦為世父 救諸苦患者 | jitsu zai ni gon shi mu no sek-ko mo ga yaku i se bu ku sho ku gen sha |

| 為凡夫顛倒 実在而言滅 以常見我故 而生憍恣心 | i bon bu ten do jitsu zai ni gon metsu i jo ken ga ko ni sho kyo shi shin |

| 放逸著五欲 墮於悪道中 我常知衆生 行道不行道 | ho itsu jaku go yoku da o aku do chu ga jo chi shu jo gyo do fu gyo do |

| 随応所可度 為説種種法 毎自作是念 以何令衆生 | zui o sho ka do i ses-shu ju ho mai ji sa ze nen i ga ryo shu jo |

| 得入無上道 速成就仏身 | toku nyu mu jo do soku jo ju bus-shin |

P.S. I’ve been posting a lot of Japanese-Buddhist liturgy from various sources, and this is the last one I will post for a while. The ones I have posted so far on the blog cover the most common sutra chants, so anyone curious to get started in a tradition (or rediscover a tradition) should hopefully find what they need. Good luck!

You must be logged in to post a comment.