Long, long ago, I wrote about the struggles in the Late Roman Republic between its version of progressives versus conservatives. The Roman Republic did not have political parties as we would know them, but the factions and disagreements on how to solve changing political issues did exist in its Senate, much as happens in the modern world.

But that’s not something limited to ancient Rome.

In the late 6th century CE Japan was still limited to a small kingdom called Yamato (大和) which had conquered most of its rival kingdoms. At this time, the ruler of Yamato was still little more than a “chieftain” of the largest territory called an ō-kimi (大君) meaning “big king”, not even emperor (tennō, 天皇) as they are called now. Further, the authority of the king depended on powerful clans who had strong influence on the government.

For example, during Emperor Yōmei’s short and problematic reign there rose a power struggle between two opposing factions, the Soga (蘇我) clan, and the Mononobe (物部), and during the interregnum after he died. One one side of the struggle was a reform faaction that wanted to modernize the government based on the based on Sui-Dynasty Chinese government models, away from the older, clan-based kingship. This faction included:

- Prince Shotoku – a man who needs no introduction to historians

- Soga no Umako – head of the once powerful Soga clan, who had ties to the Korean peninsula

If the Soga were a progressive, reform faction wanting to modernize the country using the latest imported culture from China, the Mononobe were the exact opposite. The Mononobe Clan was a conservative, traditional clan that distrusted the new imported Chinese culture, and especially the foreign-imported religion of Buddhism. They supported the more native Shinto traditions, and were on the more xenophobic side of the political spectrum. Their current head, Mononobe no Moriya, actively skirmished with Soga no Umako during Yomei’s reign.

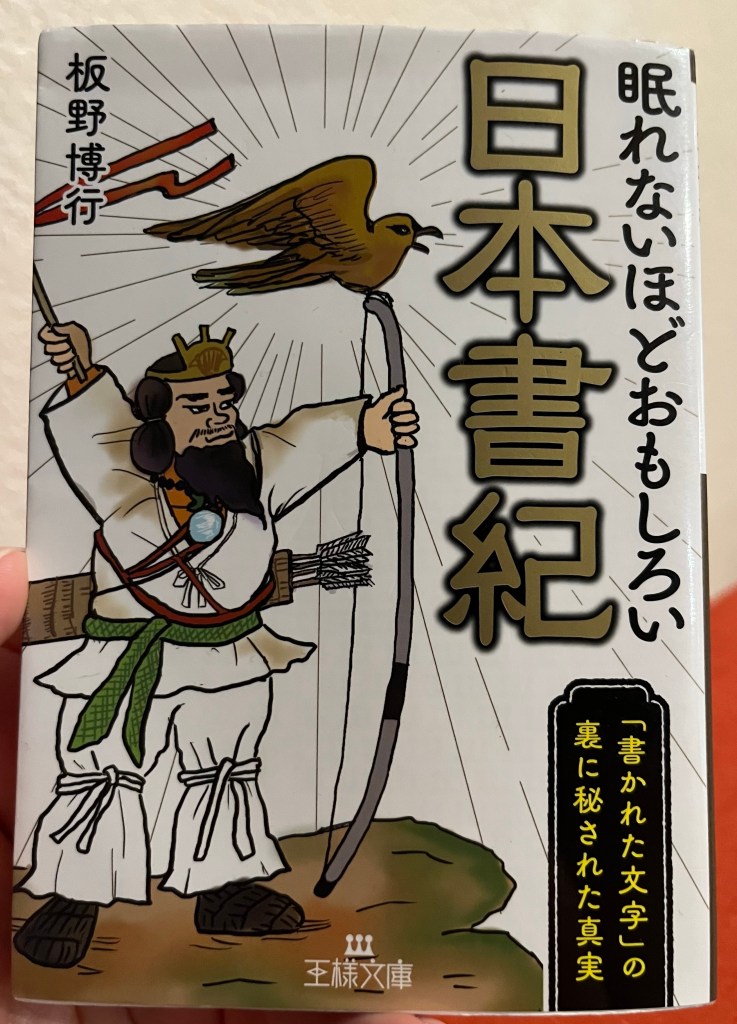

According to a historical text from the time, the Nihon Shoki (also discussed here and here), these conflicts came to a head in the year 587 after Emperor died, and a successor had to be chosen. In Japanese this is called the Teibi Conflict (teibi no ran, 丁未の乱) of 587. The Soga Clan and Prince Shotoku supported one successor, the Mononobe, the other. During the battle for succession, Mononobe no Moriya attacked Buddhist temples, and burned some of the images (often imported from the Korean kingdom of Baekje).

Finally, the battle came to a head at Mount Shigi (shigisan, 信貴山) in July of 587. The Soga lost multiple engagements at first and retreated. Then, according to tradition, Prince Shotoku, who was related to the Imperial family, fashioned a sacred branch of sumac, prayed to the Four Heavenly Kings (四天王) of Buddhism,1 promising to build a temple if they could help him trounce the Mononobe.

The subsequent battle was a complete rout for the Mononobe clan, and their leader Moriya was shot with an arrow. The rest was history: Shitenno-ji Temple, one of the oldest in Japan.

Under the reign of Empress Suiko, one of the few, powerful female monarchs in Japanese history,2 Japan further prospered under the triad of Suiko, Soga no Umako and Prince Shotoku, her advisors. Prince Shotoku in particular was said to have introduced:

- Japan’s first ever Buddhist-influenced constitution: the Seventeen-article Constitution (jūshichijō kenpō, 十七条憲法 ). It’s not a modern, legal document, but it was meant to provide a spiritual framework for governing the country.3

- Reorganized the bureaucracy into a meritocratic system based on the Chinese model, the Twelve Level Cap and Rank System (kan’i jūnikai, 冠位十二階).

- The first use of the title “Emperor” (tennō, 天皇), when Prince Shotoku addressed the Emperor of China from the “Emperor” of Japan. This was a bit of a diplomatic coup by placing Japan as a co-equal to Imperial China.

What I always find interesting about this period of Japanese history was the overtly progressive nature and forward-thinking of the government at the time, not to mention a powerful female sovereign, and how it triumphed over conservative, xenophobic thinking. Of course, by today’s standards, it doesn’t seem that progressive, and some of these reforms eventually petered out,4 or were abandoned for various reasons, but some aspects persisted up until modern times. It is also the subject of various manga over the years.

But also, what I really like about this period is that the old order wasn’t totally destroyed either. The two sides eventually just learned to co-exist for many generations (e.g. the Nara and Heian periods of Japanese history). It wasn’t a smooth transition, but the forces of history marched on nonetheless.

P.S. Fun fact, one of the supporters of the conservative Mononobe faction was a small clan called the Nakatomi. Later, the Nakatomi would become the Fujiwara, and would eventually dominate political life in Japan. History is weird.

P.P.S. Featured photo is one of many pagodas (Buddhist stupa) promulgated by Shotoku, this one in Kyoto.

1 In Sanskrit, these were the Caturmahārājakayikas or Caturmahārāja. For example, if you visit Todaiji, you see some of the Four Guardian Kings around the giant statue of the Buddha, plus many other, older temples. I liked their adaptation in Roger Zelazny’s “Lord of Light” as well.

2 There were other Empresses who reigned as well, some powerful, but many remained as temporary regents until someone else could assume the throne.

3 The modern constitution of Japan adopted in 1947, at the instigation of US Occupation Forces, is ironically significantly more progressive and modern than the US Constitution. To be fair, they were written almost 200 years apart, but the Japanese Constitution explicitly grants suffrage to women and abolishes slavery. Even now, with its amendments, the US Constitution grants neither. In college, I met the lady (a US army secretary at the time) who helped write the clause on women’s suffrage. She was a very fascinating person, though she’s probably passed away by now.

4 Many generations later, this was still largely true: powerful clans ruled many parts of Japan outside the capital, gradually evolving into a feudal system over the centuries, until the Meiji Restoration of 1868,

You must be logged in to post a comment.