“…tin-plated, overbearing, swaggering dictator with delusions of godhood.”

Scotty, “Trouble with Troubles” (s2ep15), Stardate: 4523.3

Thinking of the story of Taira no Kiyomori, among other things today.

“…tin-plated, overbearing, swaggering dictator with delusions of godhood.”

Scotty, “Trouble with Troubles” (s2ep15), Stardate: 4523.3

Thinking of the story of Taira no Kiyomori, among other things today.

Season three of Star Trek has one of my most favorite, albeit silliest episodes in the entire series: The Savage Curtain. The episode starts off with a bang: Abraham Lincoln (played by Lee Bergere) floating in space on his trademark chair.

From there, the Enterprise crew and in particular Kirk and Spock are confronted by some of “histories worst villains” as well as an encounter with Spock’s idol, Surak (played by Barry Atwater), father of Vulcan philosophy.

The rock aliens who force the “good” historical figures to combat the “evil” historical figures want to compare and contrast their philosophical ideas against one another to see which is better.

The premise might seem a bit silly, but it is a fascinating contrast of ideas:1

Although Surak loses his life in the combat, he has some really great quotes in this episode that I think are worth sharing:2

The face of war has never changed. Surely it is more logical to heal than to kill.

Surak of Vulcan, “The Savage Curtain” (s3ep23), stardate 5906.5

and also:

I am pleased to see that we have differences. May we together become greater than the sum of both of us.

Surak of Vulcan, “The Savage Curtain” (s3ep22), stardate 5906.4

Lincoln’s performance throughout the episode is great as he embodies the great American president as we want him to be: gentle, but tough when needed. One can’t help but compare this to Bill and Ted’s Excellent Adventure, even if they are completely different movies, because Abraham Lincoln is such a beloved figure.

At the very end of the episode, there is a subtle dialogue worth sharing:

KIRK: They seemed so real. And to me, especially Mister Lincoln. I feel I actually met Lincoln.

Source: http://www.chakoteya.net/StarTrek/77.htm

SPOCK: Yes, and Surak. Perhaps in a sense they were real, Captain. Since they were created out of our own thoughts, how could they be anything but what we expected them to be?

In fact, I think there’s something very Buddhist about this. The inhabitants of the planet didn’t necessarily create historically accurate versions of Lincoln, Surak, etc, but what we wanted them to be in our minds. In a sense, we create our own gods and idols through our hopes and aspirations (for good or for ill). This isn’t always bad, but it does show how unwittingly we bend the world around us to fit our beliefs and views.

Anyhow, The Savage Curtain is such a fun, surreal episode, and a fascinating contrast of ideas and people in history, and how they interact. These ideas and philosophies are timeless in many ways, and crop up over and over again in history, but by pitting a bunch of historical figures in space against once another, it takes on a whole new dimension of weird, silly, fun.

Also:

P.S. Many reviews point out that The Savage Curtain borrows elements from older, venerable episodes, and thus judge it an inferior episode. I can’t disagree that it borrows a lot of elements, but I like to think it is a capstone to several previous “moral tale” episodes. The action sequences aren’t quite as good, but I don’t think that was the point. It was battle of ideas, not sticks.

P.P.S. I bet you could take all 8 characters, including Kirk and Spock, in the battle and somehow arrange them into a classic D&D alignment chart. The rock aliens of Excalbia would probably be true-neutral.

1 I wish “Zorra” (Carol Daniels) and “Genghis Khan” (Nathan Jung) had dialogue, as it would have been interesting to have more contrasting goals and aspirations.

2 More on witnessing war.

Kang: “Only a fool fights in a burning house.”

Star Trek, “Day of the Dove” (s3ep11), stardate unknown

Ever since … recent events, I’ve been thinking about this quote a lot.

This also reminded of a passage from the Analects of Confucius:

[8:13] The Master said: “Be of unwavering good faith and love learning. Be steadfast unto death in pursuit of the good Way.1 Do not enter a state which is in peril, nor reside in one which people have rebelled. When the Way prevails in the world, show yourself. When it does not, then hide. When the Way prevails in your own state, to be poor and obscure is a disgrace. But when the Way does not prevail in your own state, to be rich and honored is a disgrace.”

Translation by Dr Charles Muller

The Analects is a compilation of Confucius’s (a.k.a. “the Master”, or “Master Kong”, etc) teachings by his disciples, completed around the 1st or 2nd century BCE. This particular passage does a nice job of summarizes Confucius’s general teachings: at all times a “gentleman” (jūn zǐ, 君子) should always stick to their principles regardless of the conditions of the world.

There are times where one openly expresses their views and strives to do what’s right, where one can share their talents for public good. But there are also times when one should bide their time, avoid getting entangled, and focus inward. Whatever is necessary to maintain one’s integrity at all times. Better to be broke but maintain integrity, than to compromise personal values for the sake of gain.

In Confucius’s time the central state of the Zhou Dynasty kingship was breaking down, and the different nobles governing each fiefdom were either breaking away and declaring themselves kings, or being overthrown by their own ministers who would in turn assert authority. It was a cutthroat time in Chinese history, and Confucius wanted no part in it.

One cannot help but find parallels even today.

P.S. Featured photo is of Kang the Klingon from the Stat Trek episode “Day of the Dove”, played by the brilliant Michael Ansara.

1 When Confucius speaks of the “Way” (daò, 道) he is using a common Chinese religious term for things like righteousness, justice, stability, and so on. The Taoist usage of the term is similar, and draws from the same “cultural well” even if nuances differ.

Author’s note: I wrote this a couple months ago, but have been so backed up, I am finally posting it now. It was not intended to relate to current events. Just Star Trek nerdism, and me philosophizing.

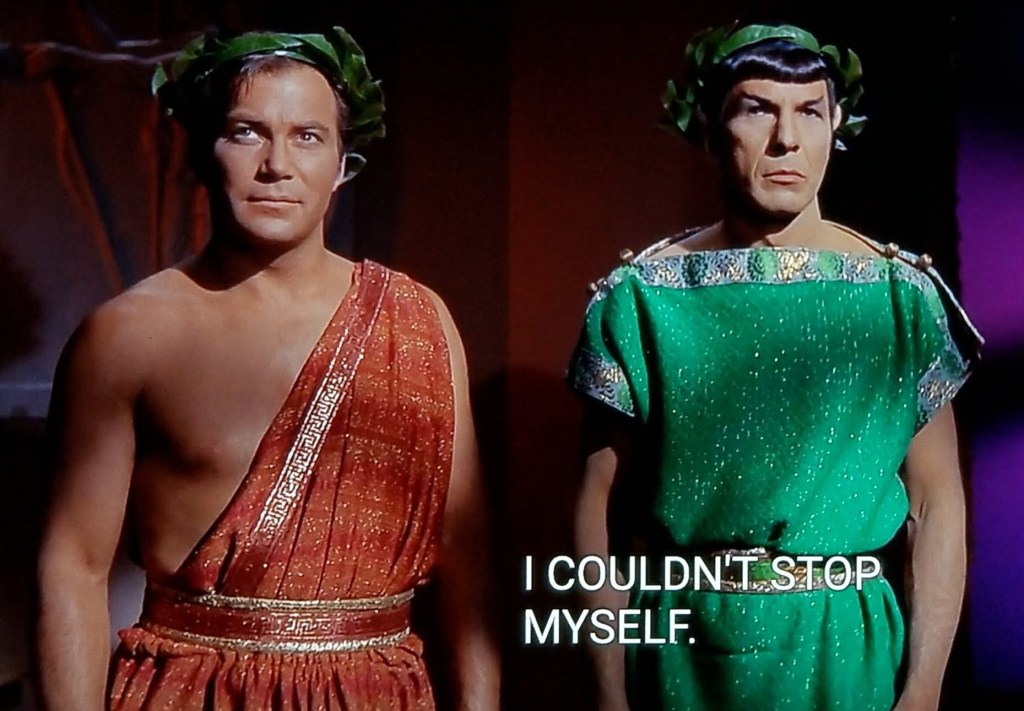

The third-season episode of Star Trek titled Plato’s Children is often criticized as one of the worst episodes of the series. It actually has a really interesting premise, but suffers from poor execution.1

The Enterprise comes to planet populated by a self-styled republic,2 modeled after ancient Greek poleis, comprised of aliens who each have tremendous psychic powers. They live in great comfort, and spend their days pursuing whatever they want, but members of this republic have become so lazy, and have atrophied so much that they can’t manage even basic first-aid. When the leader suffers from a cut, he fails to do anything about it until it becomes seriously infected.

Further, one member of the community suffers from dwarfism, and no psychokinetic powers, and the other members of the republic bully him for entertainment and menial tasks. Michael Dunn’s performance as the “dwarf” character was excellent by the way. The same members also torment the Enterprise crew for an extended period of time to get what they want.3

By the end of the episode, it’s clear that the members of this republic are perpetually bored, and half-mad from having terrific power, but nothing constructive to use it for.

Without any struggle in life, or a way to stay grounded, I think the tendency is for one to gradually go mad. People’s minds, even when satisfied with basic needs, have a tendency to create more and more subtle problems for themselves. These problems nest fractally, there is no bottom.

Further, the other major point of the episode is said by the villain Patronius when he is defeated by Kirk:

Patronius: “Uncontrolled, power will turn even saints into savages. And we can all be counted on to live down to our lowest impulses.”

Star Trek, “Plato’s Stepchildren” (s3ep10), Stardate 5784.2

This is a very unintentionally Buddhist thing to say too. The mind is capable of the heights of sainthood (or bodhisattva-hood in Buddhism), as well as the depths of depravity, and everything in between. Under the right conditions any person can become a tyrant, or a saint bodhisattva. It’s not so much a question of personal will-power, environment matters more than one might think.

It is always important to stay just a little vigilant toward one’s own mind. Perfectly rational people can easily go off the rails under the right circumstances. Further, you can’t control what others think and do (nor should you), but you can control how you react to them, or how you choose to conduct yourself. A mind unrestrained will inevitably run into disaster.

Namu Shaka Nyorai

1 Like many season 3 episodes.

2 The use of “republic” as modern people think it, is pretty different than the “res publica” as understood by Romans. It was more closer to a commonwealth, than a particular political structure, so even after Octavian took over as the princeps (the first “Emperor” in all but name), the res publica kept going well into the Easter Roman Byzantine era and beyond. By then, the Latin term was gradually replaced with the Greek equivalent: Politeia (πολιτεία).

3 This is why this episode is so unpopular. The script is pretty thin, so i guess the idea was to stretch out the time by adding more of these torment scenes.

McCoy: Well, that’s the second time man’s been thrown out of paradise.

Kirk: No, no, Bones, this time we walked out on our own. Maybe we weren’t meant for paradise. Maybe we were meant to fight our way through, struggle, claw our way up, scratch for every inch of the way. Maybe we can’t stroll to the music of the lute. We must march to the sound of drums.

— Star Trek, “This Side of Paradise”, stardate 3417.7

Been thinking about this one all weekend. With all the upcoming chaos on Tuesday, and the continued struggles in society, I guess this one really hit home.

How often mankind has wished for a world as peaceful and secure as the one Landru provided.

Spock, “Return of the Archons” (s1ep21), stardate 3192.1

Of course, every generation everywhere faces its own crises, and somehow the Human race keeps going. We stumble, we fall back, but somehow we inevitably pick ourselves up, and move forward again.

With the conclusion of the hit mini-series Shogun,1 it seemed like good time to delve into what a Shogun was. I talked a lot about the first few Shoguns of the Kamakura Period, and the Shoguns of the late Edo Period, but there’s a lot more to the story.

In early Japanese history (a.k.a. Japanese antiquity), the government was modeled on a Chinese-style, Confucian-influenced bureaucracy. This is epitomized in the Ritsuryo Code which started in 645, under the Taika Reforms, and continued (nominally) in some form all the way until 1868.

This imperial bureaucracy elevated the Emperor of Japan to the first rank, and other officials and nobility were allocated ranks below this. The ranks dictated all kinds of things: salaries, colors to wear at the Court, other rights and responsibilities, etc. There were bureaucratic offices for all sorts of government functions: land management, taxes, religious functions, military and so on.

The imperial court did not rule all of Japan as we know it today. The north and eastern parts of Japan in particular were dominated by “barbarian” groups called Emishi whose origins are somewhat obscure but are probably ethnically different than early Japanese people.

To subdue these people, certain military commanders in the Imperial bureaucracy were granted a temporary title of sei-i taishōgun (征夷大将軍), or “Supreme Commander of Barbarian-suppressing Forces”. Since a military force needs a clear chain of command, someone had to be made the supreme commander, and this was what the Shogun was meant to do.

But everything changed after the Genpei War, and the fall of the Heike Clan.

After the Genji clan (a.k.a. the Minamoto) crushed the Heike clan, they assumed military control of Japan. The head of the Genji clan, Minamoto no Yoritomo, was granted the title of sei-i taishōgun by the Emperor permanently, and given the task pacifying the rest of Japan. The title became hereditary, not temporary, and thus created a new system of government in Japan.

The original Imperial Court, and its institutions, remained in place in Kyoto. However, practical control of Japan was managed through the new bakufu (幕府) government headquartered in the eastern city of Kamakura. This began a period of history called the Kamakura Period of 1185–1333.

From here, Japan’s history and its bakufu governments can be divided like so:

| Period | Capitol | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Kamakura Period (1185–1333) | Kamakura | After Minamoto no Yoritomo‘s death, plagued with infighting and power-plays by vassals. Minamoto line died with Sanetomo’s untimely death, further heirs drawn from obscure Hojo relatives. |

| Southern Court Insurrection (1336 – 1392) | Yoshino | Emperor Go-Daigo attempts to reassert authority of the Imperial line. Kamakura Bakufu dispatches Ashikaga Takauji to suppress rebellion, but is betrayed by Takauji. |

| Muromachi Period (1336 to 1573) | Kyoto | First 3 shoguns were strong rulers, but quality of rulership slowly declines, culminating in 8th shogun Yoshimasa, and the disastrous Onin War. High point of Kyoto culture, ironically. |

| Warring States Period (1467 – 1615) | Kyoto (barely) | After Onin War of 1467, Ashikaga Shoguns still nominally rule until 1573, but country descends into civil war. Almost no central authority. |

| Oda Nobunaga (1573 – 1582) | Kyoto | After driving out last of Ashikaga Shoguns, Oda Nobunaga reaches deal with reigning Emperor and conferred titles of authority. Almost unifies Japan. Later betrayed and murdered by a vassal. |

| Azuchi-Momoyama Period (1585 – 1598) | Kyoto | After unifying Japan after Oda Nobunaga’s demise, vassal Toyotomi Hideyoshi unifies, and then rules Japan as the Sesshō (摂政, “regent to Emperor”) then Kampaku (関白, “chief advisor”). Dies in 1598, and son is too young to rule. Country falls into civil war again. |

| Edo Period (1600 – 1867) | Edo (Tokyo) | Tokugawa Ieyasu, a former vassal of Oda Nobunaga, then unifies Japan for the final time, and moves capitol to a newly fortified town of Edo (modern Tokyo). Effective policies by Ieyasu and his early descendants avoids many problems of past Shogunates, and provides stable rule for 268 years until Meiji Restoration of 1868. Similar to Muromachi period, quality of rulership gradually declines, but effective policies help maintain stability far longer.2 The last shogun, Tokugawa Yoshinobu, relinquishes authority back to Emperor at Osaka Castle in 1867. |

During this entire period of history, the Imperial line, and its Court of noble families in Kyoto never ended. The Southern Court vs. Northern Court briefly split the Imperial family into two competing thrones, but once they reunified, everything continued on as normal. The Emperors reigned, but the military governments ruled.

Once the Meiji Restoration of 1868 came, this changed, and with a new constitution borrowed from the Prussian model, the Emperor’s assumed direct control again until the modern constitution in 1947 when the Emperor returned to a mostly ceremonial role that we see today.

The series of Shogun takes place at the very end of the Azuchi-Momoyama Period to the very beginning of the Edo Period, but as you can see, Japan’s military history was far longer, and its many ruling families each faced different challenges. For the peasants on the ground, who they paid taxes to may have changed, but life overall probably remained somewhat the same.

1 I read the original book by James Clavell back in the day, including his other books: King Rat, Taipan, and so on. Great story-telling, especially King Rat (based on his personal experiences), but older me kind of facepalms now at the bad stereotypes, linguistic mistakes, and so on.

2 It’s also why, today, many historical dramas, comics and stories take place in the Edo Period. My father-in-law likes to watch one Japanese TV show called Abarenbo Shogun (暴れん坊将軍, “Unfettered Shogun”), which is a mostly fictional drama about the unusually talented 8th Shogun of the Edo Period, Tokugawa Yoshimune (1684 – 1751). In the drama Yoshimune, often traveling in disguise, solves mysteries and fights crime. It’s campy, but also a fun show to watch. The “Megumi” lantern shown on the right is a set piece from the show.

A rich man thinks all other people are rich, and an intelligent man thinks all other people are similarly gifted. Both are always terribly shocked when they discover the truth of the world.

“I, Strahd” by P.N.Elrod

Another book I have been reading lately for Halloween is the novel I, Strahd, which is a fictional autobiography of the villain of the “Barovia” fantasy-gothic horror setting: Strahd von Zarovich. As an autobiography, Strahd talks about his origins and justifies why he’s such a monster, literally and figuratively. It was one of the most popular novels of the Ravenloft series that was published in the 1990’s to promote this venerable Dungeons and Dragons setting, and is a kind of “bible” for fans of the setting due to broad number of characters, helpful backstories, and compelling story.1

But I digress.

People naturally assume their values and beliefs are pristine because that’s all they ever know, and that others will naturally agree to them. They are then shocked to discover that other functional adults subscribe to very different beliefs. Their own world is briefly shattered or they feel threatened, and conclude that such adults are just stupid, insane or evil. What follows usually isn’t good.

Even when people claim they are open to discussion or free-thinkers, I am reminded of Dave Barry’s famous quote:

People who want to share their religious views with you almost never want you to share yours with them.

Of course this applies to me as well. But on the other hand, I have to remind myself that I am not the center of the Universe. Whether I am actually right or not is irrelevant; I have to accept that not everyone comes to the same conclusions that I do, and I have no right to judge them for their views:

Gandalf: “Do not be too eager to deal out death in judgment. Even the very wise can not see all ends. My heart tells me that Gollum has some part to play yet, for good or ill before this is over.”

“Fellowship of the Ring”, by J.R.R. Tolkien

Hence the Dhammapada has the famous line:

Hatred is never appeased by hatred in this world. By non-hatred alone is hatred appeased. This is a law eternal.

Translation by Ven. Acharya Buddharakkhita

It doesn’t mean you have to be best friends with other people, but you have to accept the sheer variety of people, ideas and beliefs no matter how stupid they seem.

Spock: Madness has no purpose. Or reason. But it may have a goal.

Star Trek, “The Alternative Factor”, stardate 3088.7

You don’t have to give them oxygen either. Some ideas are better left dead. It’s about tolerance of people, not tolerance of bad ideas. Ideas are, like all phenomena, contingent and impermanent (Buddhism par excellence).

As soon as you begin to harbor ill-will toward others who are different, you will quickly spiral into a dark path of your own doing.

Namu Amida Butsu

P.S. I have a huge backlog of drafted posts lately, so you may see a few more this week. I hope you enjoy.

1 It is a terrific read, but I admit I still like Vampire in the Mists featuring his rival, the elf-vampire Jander Sunstar, even more. Strahd is definitely *not* the hero in that tale. Heart of Midnight was also an excellent read and a close third for me. To be honest, all the novels I’ve read int he series so far, even the less compelling ones, are still good reads.

Spock: No one can guarantee the actions of another.

Star Trek, “Day of the Dove” (s3ep7), stardate unknown

The third season of the classic TV series, Star Trek, gets a lot of flak for being lower in quality, but some of the best episodes of the series can be found there. One of my personal favorites is “Day of the Dove”.

The premise is strange at first glance: the Enterprise crew and a group of Klingon prisoners are trapped on the Enterprise by a phantasmal alien that feeds on anger and conflict, which keeps manipulating both sides in order to instigate them into hopeless, unending cycle of conflict. The alien furnishes weapons, seals corridors, plants false memories, and heals fatal injuries all so that the Enterprise crew and Klingons fight can ad infinitum, even as the ship is hurling out of control beyond the edge of the galaxy.

There’s a lot to unpack in this episode, and much of it still relates to circumstances today. But I’ll let you the reader decide for yourself.

In any case, Spock’s quote above illustrates something very Buddhist in my opinion: people expect other people to think and feel the way they do. When they don’t, we get frustrated. We naturally tend to see our own viewpoint as “pristine” and the more other’s deviate from this, the weirder or aberrant they are. We get frustrated when we they don’t do what we expect them to do. This can also happen between spouses, co-workers, and so on.

But as Spock rightly implies, this is arrogant, irrational, and dare I say “illogical”. We are not the center of the Universe, why should other people think and do as we do?

In the classic Buddhist text, the Dhammapada, are the following verses:

- One who, while himself seeking happiness, oppresses with violence other beings who also desire happiness, will not attain happiness hereafter.

- One who, while himself seeking happiness, does not oppress with violence other beings who also desire happiness, will find happiness hereafter.

- Speak not harshly to anyone, for those thus spoken to might retort. Indeed, angry speech hurts, and retaliation may overtake you.

- If, like a broken gong, you silence yourself, you have approached Nibbana,1 for vindictiveness is no longer in you.

[skipping for brevity…]

142. Even though he be well-attired [instead of dressed like a humble monk], yet if he is poised, calm, controlled and established in the holy life, having set aside violence towards all beings — he, truly, is a holy man, a renunciate, a monk.

translation by Acharya Buddharakkhita

Oftentimes, it is simply better to let go, let people be who they are, even if they are wrong or short-sighted, and wish them no harm.

Namu Shakamuni Butsu

Namu Amida Butsu

1 Nibbana is the Pali-style pronunciation of Nirvana. Both mean the same thing in a Buddhist context: liberation, unbinding, freedom. A Buddha’s awakening to the truth (e.g. enlightenment) leads to a state of letting go, unbinding. The Buddha Shakyamuni described it as a flame extinguished.

Something that’s been on my mind lately is this quote from the original Star Trek series:

Dr. McCoy: Spock, I’ve found that evil usually triumphs – unless good is very, very careful.

Star Trek, “The Omega Glory” (1968)

These days, pretty much the entirety of the 2020’s in particular, it really feels like good has to extra vigilant, doesn’t it? Like wherever one turns, evil seems to always get the upper hand.

This isn’t even just a statement of politics. We are definitely living through some pretty difficult times, and it brings out the worst in others.

Consider this iconic quote from the Buddhist text, the Dhammapada:

Trans. Acharya Buddharakkhita

183. To avoid all evil, to cultivate good, and to cleanse one’s mind — this is the teaching of the Buddhas.

The statement is pretty vague, but to me it feels like there’s an order and logic to this statement.

Avoiding all evil begins with things like the Five Precepts and is probably the first step as a Buddhist. It doesn’t solve everything, but it’s a good starting point. You’re stemming the worst instincts at least.

Next, one cultivates good through Buddhist practice such as dedication of merit, the four bodhisattva vows, and just good old-fashioned metta. The idea being that cultivating wholesome states of mind gradually sinks in and reinforces itself. Presumably.

Finally, cleansing the mind. This is where practices like meditation, mindfulness and such really come in handy. Having a good heart is not enough: one needs to balance it with wisdom and clarity.

In another episode of Star Trek, titled “The Savage Curtain” (the one with Space Lincoln), the founder of Vulcan philosophy Surak heedlessly goes alone to try and negotiate peace. His stubbornness costs him his life. Lincoln also tries to save him but gets killed as well.

This theme repeats across multiple episodes: striving to do good not enough, one needs to vigilant. On the other hand, being passive and intellectual doesn’t accomplish much good either.

So, you need both.

Even in these difficult times, it’s helpful to maintain goodwill towards all beings (even the really awful jerks who might not deserve it), have realistic expectations, meet evil with good, but also meet ignorance with wisdom including your own.

I’ve talked about the first shogun of Japan’s new Kamakura government, Minamoto no Yoritomo and his betrayal of his vassals here and here, but I also alluded to his execution of his younger half-brother, Minamoto no Yoshitsune. Yoshitsune’s downfall is indeed a sad tale. But as we’ll see, Yoritomo’s own downfall, while slower, wasn’t much better.

Minamoto no Yoshitsune was a military genius and the youngest of nine sons of Minamoto no Yoshitomo (Yoritomo was the oldest). When Yoshitomo was executed by his rival, Taira no Kiyomori, the half brothers were all scattered in exile, but gradually reunited under Yoritomo. Out of these brothers, Yoshitsune was the most talented in warfare. Yoshitsune led the led against the Heike clan and eventually destroyed it in the battle of Dan-no-ura.

Yoshitsune has been celebrated throughout Japanese history as the ultimate warrior, who along with his companion Benkei, went on many adventures and fought many battles. Yoshitsune’s bravery and unconventional strategies, coupled with Benkei’s stalwart strength and loyalty have been the subject of many Noh and Kabuki plays, as well as many works of art.

But one thing Yoshitsune was not good at was politics. Once the Heike were destroyed, tensions rose between the new military commander (shogun 将軍), namely his older half-brother Yoritomo, and the conniving emperor Go-Shirakawa. The Imperial family had lost power due to the Heike clan, and were eager to get it back. The Genji clan defeated the Heike and weren’t keen to hand over their hard-fought power.

Yoshitsune was caught between these two men, and used as a proxy for their struggle for power. The Emperor, grateful for Yoshitsune’s efforts appointed him Kebiishi (検非違使): the Sheriff of Kyoto the capitol. Accepting this position, however, meant that Yoshitune was now working under the Emperor, not his half-brother the Shogun, and Yoritomo was evidentially furious by this. From here on out, he began to suspect his baby brother of plotting to overthrow him. The historical drama, Thirteen Lords of the Shogun, implies that certain retainers, perhaps jealous of Yoshitsune, may have been whispering in Yoritomo’s ear, fanning his paranoia further. When Yoshitsune tried to return to Kamakura to talk to his brother directly, he was refused entry and had to idle in the nearby town of Koshigoé.

While staying at Koshigoe, Yoshitsune wrote the following letter to his older brother:

So here I remain, vainly shedding crimson tears….I have not been permitted to refute the accusations of my slanderers or [even] to set foot in Kamakura, but have been obliged to languish idly these many days with no possibility of declaring the sincerity of my intentions. It is now so long since I have set eyes on His Lordship’s compassionate countenance that the bond of our blood brotherhood seems to have vanished.

Source: Wikipedia

Yoshitsune was unable to ease his older brother’s concerns, nor did he want to be under control of the Emperor either, so he bowed out, and retreated to the province of Ōshū way up north, where he had previously been exiled. It was familiar land, and the ruler of Oshu promised to watch Yoshitsune on behalf of Yoritomo, while also protecting him from Yoritomo. With his mistress, Shizuka,2 they moved there and things were quiet for a time.

However, Yoritomo wasn’t satisfied. When Yoshitsune’s keeper passed away, the keeper’s son hatched a plan with Yoritomo to allow Yoritomo’s troops to attack his Yoshitsune’s house.

Legends hype up this last stand by Yoshitsune (with Benkei defending), but in any case, Yoshitsune the famed military commander was killed by his own half-brother, and his head was preserved in a box with sake. Yoshitsune was later enshrined as a kami at Shirahata Shrine in Fujisawa.3

Yoshitsune died in 1189, and by 1192 Yoritomo was in full control of Japan since the Emperor had died as well. As the shogun, the supreme commander of military forces, no one could oppose Yoritomo any longer, the country had been pacified at last, and he had avenged his father for his wrongful death.

……..but, this came at a steep, steep price. Yoritomo had to dodge other assassination attempts, and spent the remaining years of his life constantly watching his back. He had paid for his power in blood and betrayal, and even after taking tonsure as a Buddhist monk,4 he never really found any peace. When he died at age 51, more than a few probably sighed in relief. Yoritomo was powerful, and crafty, but he was brutal and paranoid, and everyone around him spent their lives in constant fear. One can not help but see the similarities to certain dictators today.

P.S. if you go to Tsurugaoka Hachimangu shrine in Kamakura, Japan, you can see a tiny museum, just to the left of the inner sanctum, which has relics from Yoritomo’s life. It’s easy to miss, but tickets are cheap, and it’s amazing to see. We saw it in December 2022, just after watching the historical drama, and it was pretty amazing. The new, larger museum near the front entrance is also great. A visitor can easily spend half a day at Tsurugaoka Hachimangu, especially if you are a history nerd.

P.P.S. Official website for Shirahata Shrine in Fujisawa. No English, sorry, but it’s close to Fujisawa station if you’re in the neighborhood.

1 I couldn’t find a good translation of Kebiishi in English, but based on the duties, and based on varied definitions of “Sheriff” in English-speaking countries, this seemed the closest equivalent. Needless to say, being the sheriff of the capital city was a prestigious honor, but also comes with plenty of political strings attached.

2 Another revered character in the plays and art about Yoshitsune. Yoshitsune had married another one for political reasons, and Shizuka was technically his concubine, but they seemed to have genuinely loved one another and so she alone stayed with Yoshitsune at Oshu. She is often revered for her sincere, loving devotion, and for their doomed fate.

3 When we visit family friends in Japan, we often go to Fujisawa. It’s a nice seaside town, but I never knew that Yoshitsune was enshrined here. I might try to stop by one of these days and get a stamp for my book.

4 A Buddhist monk, as in an bhikkhu or renunciant. More on the terminology here. The practice of retiring to the monastic life was a common practice among the nobility in pre-modern Japan. His wife, Hojo no Masako, not only retired to the monastic life, but still took the reins of power after Yoritomo’s death becoming the famous “warlord nun“. Go-Shirakawa, the scheming emperor, had technically retired to the monastic life as well, but only as a means of dodging certain constraints on his power by the Fujiwara clan. Politics were…. complicated in those days, and few who retired truly let go of power, despite the Buddhist prohibition for Buddhist monks to be involved in politics. Then again, even now some monks fail to heed this prohibition either. Once again, politics and religion should not mix.

Also, at the risk of being sanctimonious, I wonder if Yoritomo’s Buddhist devotion did him much good in the afterlife, given how many people he had murdered. This is not unlike the ancient king in India, Ajatashatru, who while devoted to the historical Buddha Shakyamuni, had also murdered his way to the top. Because of the weight of his crimes, Ajatashatru’s devotion and progress on the Buddhist path was greatly hindered for many lifetimes to come according to Shakyamuni. I can’t help but think Yoritomo suffered the same fate. In other words, we all pay our debts some time.

You must be logged in to post a comment.