“Many times have I repented of having spoken, but never have I repented of having remained silent.”1

Saint Arsenius the Great

I found this really neat quote from Saint Arsenius, one of the most famous of the “Desert Fathers” in the early Christian tradition from the 3rd century CE, and wanted to share it. It overlaps very nicely with similar teachings in Buddhism.

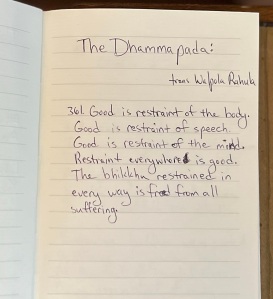

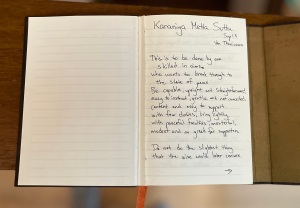

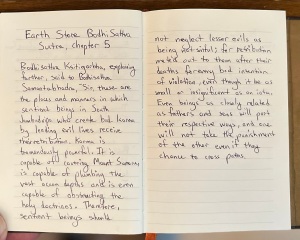

The Buddha spoke about “right speech” in several suttas in the Pali Canon, but this a good summary of what the Buddha said were appropriate times to speak, and inappropriate times to speak:

“In the same way, prince:

[1] In the case of words that the Tathāgata knows to be unfactual, untrue, unbeneficial [or: not connected with the goal], unendearing & disagreeable to others, he does not say them.

[2] In the case of words that the Tathāgata knows to be factual, true, unbeneficial, unendearing & disagreeable to others, he does not say them.

[3] In the case of words that the Tathāgata knows to be factual, true, beneficial, but unendearing & disagreeable to others, he has a sense of the proper time for saying them.

[4] In the case of words that the Tathāgata knows to be unfactual, untrue, unbeneficial, but endearing & agreeable to others, he does not say them.

[5] In the case of words that the Tathāgata knows to be factual, true, unbeneficial, but endearing & agreeable to others, he does not say them.

[6] In the case of words that the Tathāgata knows to be factual, true, beneficial, and endearing & agreeable to others, he has a sense of the proper time for saying them. Why is that? Because the Tathāgata has sympathy for living beings.”

From https://www.dhammatalks.org/suttas/KN/StNp/StNp3_3.html, translation by Thanissaro Bhikkhu

Put simply: if it is timely, true and beneficial you should speak. Besides that, think twice.

This is harder than it looks.

As a chatty person, I tend to talk a lot in person, crack jokes, etc. Learning to speak only when it’s necessary and beneficial is kind of hard.

On the other hand, how many times have I shot myself in the foot for saying something I shouldn’t?

A wise minister once told me that speech is like toothpaste. Once out of tube you can’t put it back in.

Namo Shakyamuni Buddha

P.S. Another, much older post about silence.

1 I wasn’t able to find the original source text, but it seems related to a text called the Sayings of the Desert Fathers. Beyond that, I don’t know much else, but I am hoping someone with more experience can help point the way.

You must be logged in to post a comment.