Now, I, Vairocana Buddha am sitting atop a lotus pedestal;

On a thousand flowers surrounding me are a thousand Sakyamuni Buddhas.

Each flower supports a hundred million worlds; in each world a Sakyamuni Buddha appears.

All are seated beneath a Bodhi-tree, all simultaneously attain Buddhahood.

All these innumerable Buddhas have Vairocana as their original body.

The Mahayana version of the “Brahma Net Sutra”, translation by Young Men’s Buddhist Association

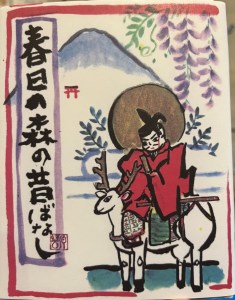

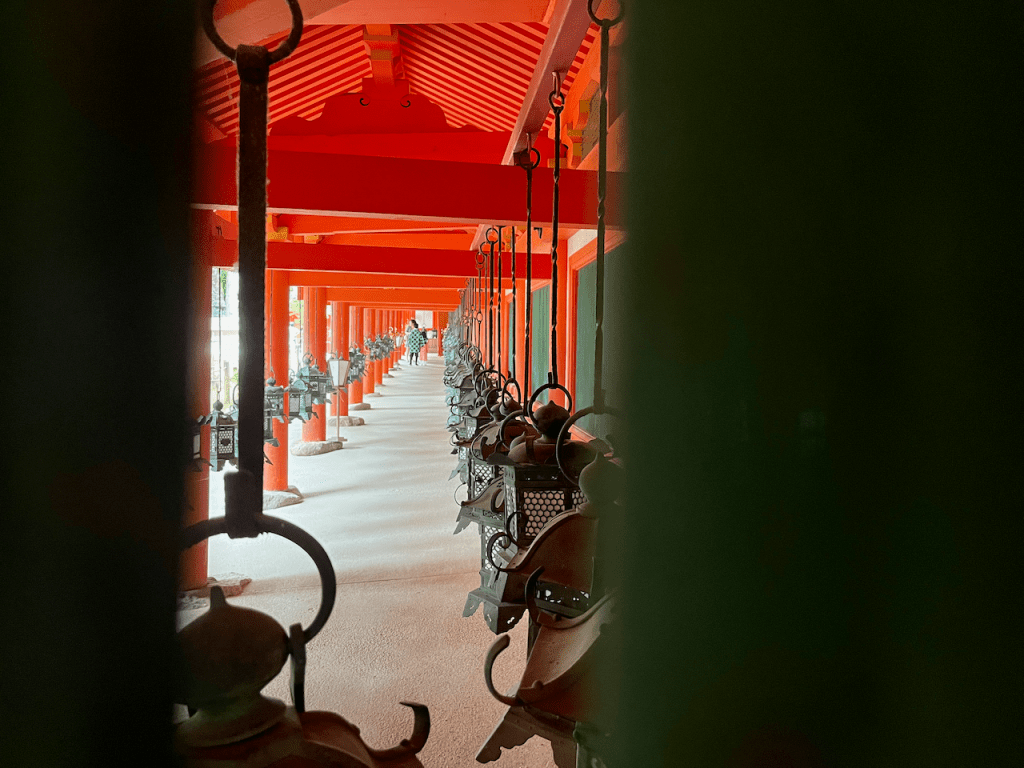

If you ever visit the famous Todaiji temple in Nara, Japan, you will see a truly colossal structure like so:

Inside as you approach is a colossal Buddha statue:

This picture does not convey the size very well. It’s truly massive. But what is this Buddha?

This Buddha is a somewhat obscure figure named Vairocana (pronounced Wai-ro-chana) in Sanskrit, which means something like “of the Sun”. So, Vairocana is the Buddha of the Sun.

Vairocana features in a few Buddhist texts in the Mahayana canon: the Brahma Net Sutra quoted above and the voluminous Flower Garland Sutra, for example. It is also very prominent in esoteric traditions in Japan (Shingon and Tendai sects) as Maha-Vairocana (“Great Buddha of the Sun”).

The Brahma Net Sutra introduced Vairocana and explains that all Buddhas that appear in such-and-such time and place are embodiments of Vairocana. Thus Vairocana isn’t just another buddha, but is their source. Vairocana, in other words, embodies the Dharma.

That is why in the Great Buddha statue above at Todaiji Temple, you see rays of light emanating outward with “mini Buddhas” among them. Each of these Buddhas is thought to have the same basic origin story as the historical Shakyamuni Buddha. Hence in the text they are all just called “Shakymunis”. All these Buddhas have the same basic qualities ( Chapter Two of the Lotus Sutra teaches the same thing, by he way), one is the same as all the others.

This is primarily a Mahayana-Buddhist concept, but has precedence in pre-Mahayana sources. Consider the Vakkali Sutta from the Pali Canon:

“Enough, Vakkali! What is there to see in this vile body? He who sees Dhamma, Vakkali, sees me; he who sees me sees Dhamma. Truly seeing Dhamma, one sees me; seeing me one sees Dhamma.”

Translation by Maurice O’Connell Walshe

So the historical Buddha, founder of the Buddhist religion, Shakyamuni, is telling his disciples that his personage is less important than the Dharma. Mahayana Buddhism simply applies this same teaching towards all the Buddhas.

Also, some Buddhist texts assign different Buddhas to this role: the “cosmic” Shakyamuni Buddha of the Lotus Sutra or Amida Buddha in interpretations.

But it doesn’t really matter what you call this embodiment of the Dharma.

What matters, I think, is that the source of Buddhist wisdom is the Dharma, not a specific teacher, and that the Dharma pervades everywhere, regardless of the particular community, or lack thereof….

You must be logged in to post a comment.