Hello readers,

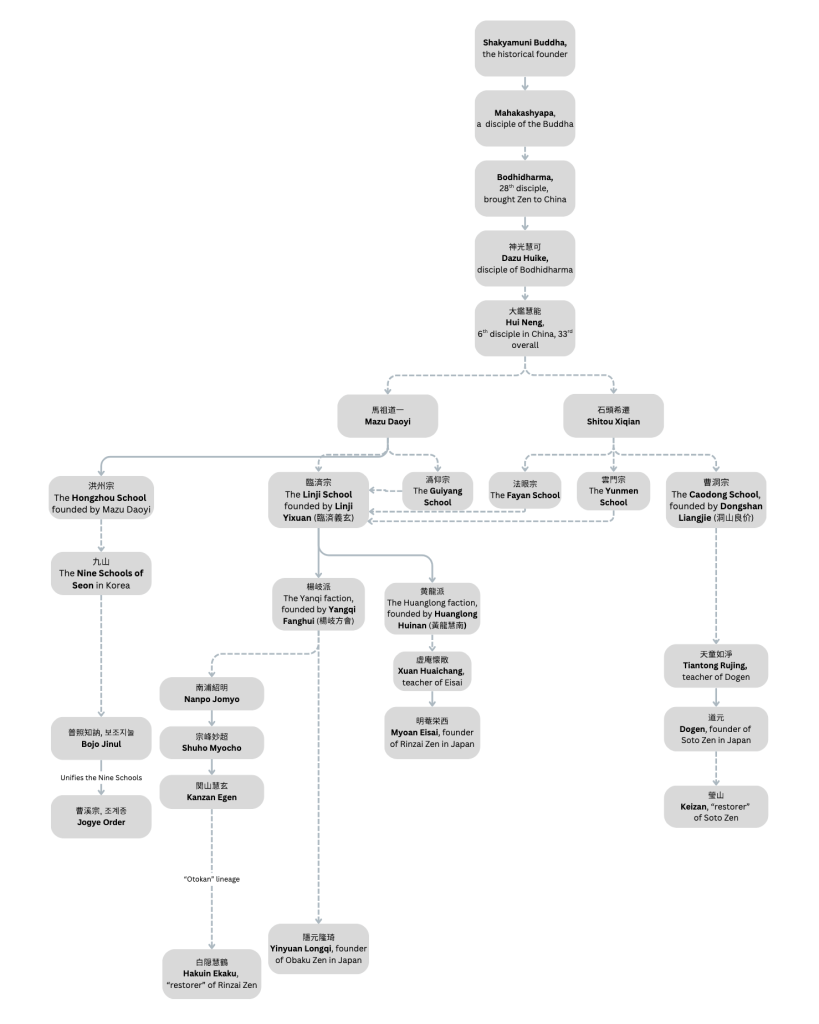

In late 2025, by chance, I found an interesting book at the local Japanese bookstore titled 眠れなくなるほど面白い図解禅の話, “An explanation of Zen so interesting you can’t sleep”, which provides a nice overview for Japanese readers about Zen. It covers a lot of little details like different sects, founders, historical bits, cultural stuff, and so on, that are hard to find in English publications.

Anyhow, the book talks about something I’ve never heard before called the Shiseiku (四聖句) which can be translated as “The Four Holy Verses [of Zen]”. This is a set of verses, imported from Chinese Chan Buddhism and attributed to Bodhidharma, and distill what Zen is all about:

| Chinese / Simplified1 | Pinyin | Sino-Japanese | English2 |

|---|---|---|---|

| 不立文字 / 不立文字 | bù lì wén zì | fu ryū mon ji | “Buddha-nature cannot be expressed in words.” |

| 教外別傳 / 教外别传 | jiào wài bié chuán | kyō ge betsu den | “The teachings of Buddha-nature exist outside scripture.” |

| 直指人心 / 直指人心 | zhí zhǐ rén xīn | jiki shi nin shin | “The heart of the Buddha’s teachings are transmitted directly, person to person.” |

| 見性成佛 / 见性成佛 | jiàn xìng chéng fó | ken shō jō butsu | “A person who sees their own true nature is a buddha.” |

Let’s break these down.

The gist is that the deeper teachings of Buddhism cannot be expressed in words, but must be experienced first-hand. This is not an exclusive concept to Zen, by the way. Take a look at an early sutra of the Buddhist tradition:

“This Dhamma that I have attained is deep, hard to see, hard to realize, peaceful, refined, beyond the scope of conjecture, subtle, to-be-experienced by the wise.

The Ayacana Sutta (SN 6.1), translation by Ven. Thanissaro Bhikkhu

… among other places:

36. “When a monk’s mind is thus freed, O monks, neither the gods with Indra, nor the gods with Brahma, nor the gods with the Lord of Creatures (Pajaapati), when searching will find on what the consciousness of one thus gone (tathaagata) is based. Why is that? One who has thus gone is no longer traceable here and now, so I say.

The Alagaddupama Sutta (MN 22), translation by Nyanaponika Thera

Buddhism provides signposts, maps, or guides through the sutras, through Dharma talks (sermons), and such. However, sooner or later one has to apply the teachings themselves to fully grasp it. This includes one’s own “Buddha nature”: that capacity we have toward becoming buddhas ourselves.

Although Zen tends to have an anti-intellectual image, it’s important to understand that there is a genuine need for scriptural texts and references, especially as one starts out. The Buddha even warns us about making bad assumptions before fully grasping the Dharma, like trying to grasp a poisonous viper incorrectly.

But over the years, through practice this become less essential. Life is something to experience, to live, and to learn from. Even the really ugly shit. In the same way, imagine a pilot training to fly. Reading the manual isn’t enough; they must put in enough hours of “flight time” before they get a license.

But I digress.

The final verse (a buddha is one who sees their own nature) needs some extra explanation. What separates a buddha from a mundane human being is a degree of awakening, not supernatural powers. Or as Dogen Zenji explains in the Genjō Kōan:

To study the Buddha-Way is to study the Self. To study the Self is to forget the Self. To forget the Self is to be enlightened by all things. To be enlightened by all things is to drop off the body and mind of self and others.

In other words, through Buddhism, you see your own nature. By seeing your own nature, you drop the delusions and gain clear insight. By gaining clear insight, you awaken as a Buddha.

Easy? NO.

Possible? Yes.

Namu Shakamuni Butsu

1 For those unfamiliar, Chinese characters come in the traditional form and simplified form. The traditional form is what you mainly see outside of the People’s Republic of China. The simplified form is mostly used within the PRC. Interestingly, Japanese uses halfway solution: some characters are simplified, some are not. Anyhow, in most cases, the characters are the same, but you can probably spot a few differences.

2 This is my own translation. Apologies in advance for any mistakes.

You must be logged in to post a comment.