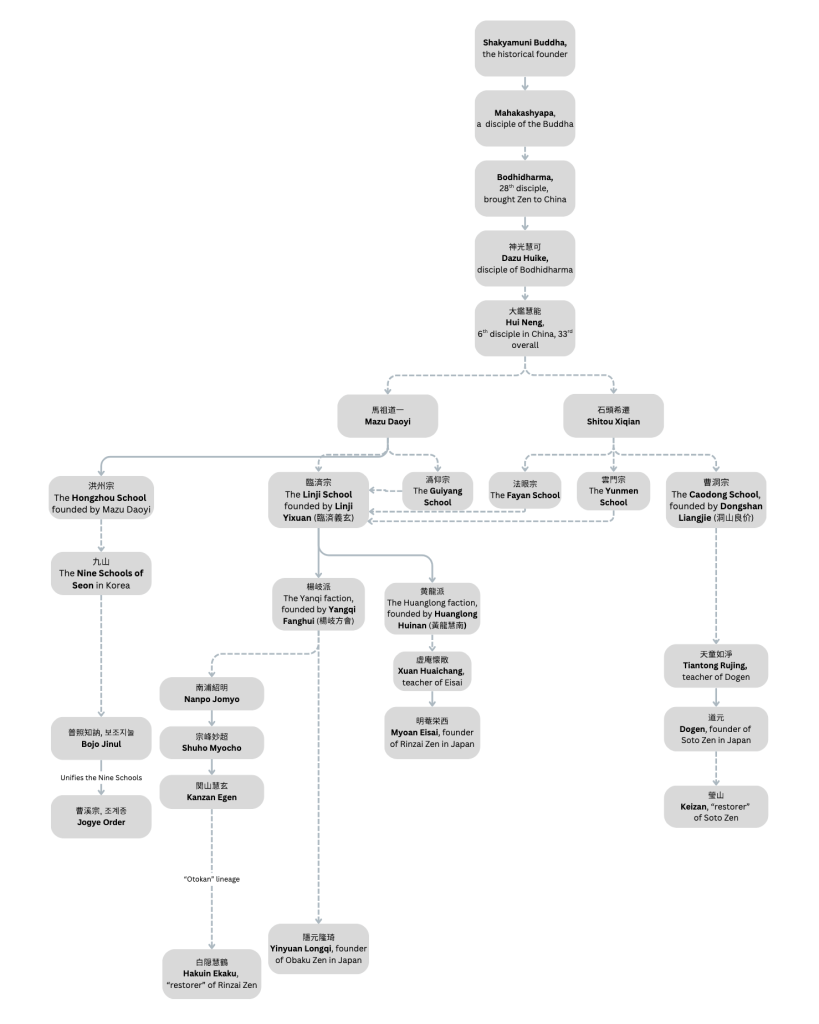

Recently, I found myself stuck in one of my usual nerd “rabbit holes” of trying to make sense of Zen lineages in Japanese Buddhism, but this led to a more complicated rabbit hole of making sense of the source “Chan” (Zen) lineages in China. This started after reading my new book on Rinzai Zen, which included a nice chart. At first, I tried to emulate and translate that chart in Canva, but then I realized it was missing some critical details, so I kept adding more. This is the result (click on the image for more detail):

Let’s go over this a bit so it makes more sense.

The premise behind all Zen sects regardless of country and lineage is that Zen started when the historical Buddha, Shakyamuni, supposedly held a flower up to his disciples and said nothing. Everyone was confused except his disciple Maha-Kashyapa who smiled in understanding. From here, according to tradition, the teachings were passed down from teacher to disciples for 28 generations in India, culminating in a monk named Bodhidharma who came to China.

The history up to this point is somewhat vague, and possibly apochryphal, but easy to follow.

This continues for a few more generations in China, until you get to a monk named Hui-Neng (Enō in Japanese)1 who is the supposed author of the Platform Sutra, a Chinese text. As the 6th “patriarch” of the lineage in China, he establishes what we know today as “Chan Buddhism” or Chinese Zen.

Things become more complicated a couple generations later as two descendants: Mazu Daoyi2 and Shitou Xiqian3 directly or indirectly found different schools of Chan Buddhism. This is known as the Five Houses of Chan period during the Tang Dynasty. Thus, the entire Chan/Zen tradition as we know it today is derived from Hui-neng and transmitted through these two men.

Out of the five houses, the Hongzhou,4 Lin-ji and Cao-dong5 all survive in some form. The others are gradually absorbed into the Lin-ji school, which in the long-run is what becomes the most widespread form of Chan Buddhism in China. The Cao-dong school is the one exception, while the Hongzhou school’s success in Korea helps establish 8 out of 9 of the “Nine Schools of Seon (Chan)”6 in Korea. It through Bojo Jinul’s efforts in Korea that these nine schools are unified into the Jogye Order (homepage) which absorbed other Buddhist traditions in Korea into a single, cohesive one.

Meanwhile, in Japan, the Lin-ji and Cao-dong schools find their way to Japan where the names are preserved, but pronounced different: Rinzai and Soto respectively. Rinzai’s history is particularly complicated because they were multiple, unrelated transmissions to Japan often spurred by the Mongol conquest of China. Of these various Rinzai lineages, the two that survive are the “Otokan” Rinzai lineage through Hakuin, and the “Obaku” lineage through Ingen, but eventually the Otokan lineage absorbed the Obaku lineage. Today, Rinzai Zen is more formally called Rinzai-Obaku, or Rinnou (臨黄) for short. This is a bit confusing because Rinzai came to Japan under a monk named Eisai, and his lineage did continue for a while in Japan especially in Kyoto, but the lineage from the rival city of Kamakura ultimately prevailed and absorbed other Rinzai lineages. Obaku Zen arrived pretty late in Japanese-Buddhist history, and as you can see from the chart has some common ancestry with Rinzai, but also some differences due to cultural divergence and history.

Soto Zen’s history is quite a bit more streamlined as it had only one founder (Dogen), and although it did grow to have rival sects for a time, Keizan was credited for ultimately unifying these though not without some controversy even into the 19th century.

Anyhow, to summarize, the entire tradition started from a legendary sermon by the Buddha to Maha-Kashyapa, and was passed on over successive generations in India to a legendary figure who came to China and starting with Hui-neng became a tree with many branches. Yet, the roots are all the same. Speaking as someone who’s relatively new to the tradition, I realize while specific liturgy and practices differ, the general teachings and intent remain the surprisingly consistent regardless of culture or label.

Hope this information helps!

P.S. I had trouble deciding which term to use here: Zen or Chan or Seon since they all literally mean the same thing, but are oriented toward one culture or another. If this all seems confusing, the key to remember is that the entire tradition of Zen/Chan/Seon (and Thien in Vietnam) is all one and the same tree.

P.P.S. I realized that I never covered the Vietnamese (Thien, “tee-ehn”) tradition, but there’s so little information on it in English (and I cannot read Vietnamese), that I will have to differ that to another day.

1 Pronounced like “hwey-nung” in English.

2 Pronounced like “ma-tsoo dow-ee” in English.

3 Pronounced like “shih-tow shee-chee-yen” in English.

4 Pronounced like “hohng-joe” in English.

5 Pronounced like “tsow-dohng” in English.7

6 The Korean word “Seon” is pronounced like “sawn” in English. It is how the Chinese character for Chan/Zen () is pronounced in Korean Language.

7 If you made it this far in the post, congrats! I had to put so many footnotes in here because the Pinyin system of Romanizing Chinese words is a little less intuitive than the old Wade-Giles system. Pinyin is not hard to learn. In fact, I think Pinyin is better than the old Wade-Giles system (more “what you see is what you get”), but if you don’t learn Pinyin it can be confusing.better This is always a challenge with a writing system that strictly uses ideograms (e.g. Chinese characters). How do you write 慧能 into an alphabetic system that foreigners can intuitively understand. Also, which foreigners? (English-speaking, French-speaking, Spanish-speaking, etc). Anyhow, if you are interested in learning Chinese, I highly recommend learning Pinyin anyway because it’s quick and easy to pick up. BTW, since I posted about Hokkien recently it also has two different Rominzation systems: Pe̍h-ōe-jī (old, but widespread) and Tâi-lô (Taiwan’s official revised system).

You must be logged in to post a comment.