While reading my introduction book in Japanese about Rinzai Zen, I came across a famous set of paintings that I had totally forgotten about for thirty years.

Many, many moons ago, I was a cocky 17-year old first learning about Buddhism, and Mr Pierini was my World Religions teacher in high school. Mr Pierini was a charming, older Italian-American gentleman who had a lovely opera voice, and loved sharing cool ideas with us kids. This is how I first started to explore Buddhism beyond reading books at home.1

There were a number of things I learned about Zen then that seemed really cool and mystical. Looking back they made no sense to me, but they were fascinating. It sounded “cool” to be Zen, but admittedly, I was young, clueless, showing off, and knew nothing. Among the things I read about at the time were the Mumonkan and the Ten Oxen, texts that (I realize now) are both related to the Rinzai Zen tradition.

The Ten Oxen (shíniú 十牛 in Chinese) is a famous set of ten paintings, with poetic captions that were composed in the Southern Song Dynasty of China. The powerful Song Dynasty lost the northern half of China to the barbarian Jin Dynasty,2 and retreated to the south beyond the Yangtze River, where it held on for another 150 years. Despite having their back to a wall, the southern Song Dynasty oversaw a wonderful flowering of Chinese culture, including Buddhism, and especially Chinese “Chan” (Zen) Buddhism. This is also noteworthy, because historically this is the time when such monks as Eisai and Dogen both came to China from Japan to study Zen.3

The use of oxen as a symbol for taming the mind in Buddhism, according to Wikipedia, dates way back to early India including such texts in the Pali Canon as the Maha-gopalaka Sutta, but the Ten Oxen were a way to visually explain the Buddhist path (as described in the Chan/Zen tradition) to readers as a nice easy introduction. There were, evidentially several versions in circulation, but in Japan the version by one Kakuan (Chinese: Kuòān Shīyuǎn, 廓庵師遠) from the 12th century was all the rage during the Five Mountains Period of Japanese-Buddhist history. It is since known as the jūgyūzu (十牛図).

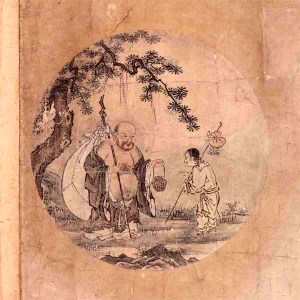

My book has a nice, down to earth explanation of the ten oxen and what they mean, so rather than posting the images with poetry, I wanted to share the simple explanations here. The illustrations are from Wikimedia Commons, and were originally painted by one Tenshō Shūbun (天章周文; died c. 1444–50).

Searching for the ox

The cowherd is searching for his lost ox. The book explains that this is like someone looking for their lost Buddha-nature: that potential within us to awaken to full Buddha-hood (a.k.a. “Enlightenment”).

Footprints sighted

The cowherd now finds the footprints of his missing ox. This is like the Buddhist disciple who studies the Dharma (e.g. “Buddhism”), and gets the first hints at the true nature of things.

Ox sighted

Just as the cowherd sees his lost ox at last, the disciple of the Buddha grasps the point of the Dharma is (i.e. what’s it all about).

Grasping the Ox

One moment the cowherd has grasped the ox, another moment he is about to lose it. In the same way, my book explains that a person may perceived their true nature one moment, but lose sight of it again. The Buddhist disciple is still inexperienced and lacks certainty.

Taming the Ox

The wayward ox is now under control and lassoed, so the cowherd escorts it back home. For the Buddhist disciple, my book explains that through self-discipline such as the precepts, one’s delusions and conduct are brought to heel. This doesn’t mean they have resolved things, and one can still backslide, but at least they are under control now.

Riding the Ox

The cowherd is now confidently riding atop the ox, playing a flute. This means that one’s Buddha-nature is expressed through one’s form and behavior.

Forgetting the ox

Now that the cowherd is safely home with the ox, the ox is no longer a concern. My book explains that this symbolizes Enlightenment as one attains peace of mind.

Forgetting the distinction between self and ox

Here this empty circle expresses the Zen ideal that all is empty, and that there’s no distinction between oneself and the ox, or anything else for that matter; this is the Heart Sutra in a nutshell.

Back to basics

Having awakening to the nature of all things, things “return to the source” in a sense, or put another way, one sees mountains and mountains, trees as trees, etc. No more, no less.

Returning to society

My book explains that the cowherd now appears like Hotei (Chinese: Budai), the famous, jolly-looking figure in Chinese Buddhism and is in turn sharing the Dharma with another young cowherd. This cowherd will undergo the same quest, starting at picture one above.

In other words, everything comes full-circle.

In the same way, I don’t think teenage me imagined myself blogging about this 30 years later, and a bit more experienced, but life is funny that way.

Namu Shakamuni Butsu

1 Mr Pierini, thank you. 🙏🏼

2 Both would ultimately be destroyed by the Mongols especially under Kublai Khan who formed the Yuan Dynasty. This period of time is important to Japanese Zen history too because the influx of Chinese monks, especially Rinzai monks, to Kamakura-period Japan helped fuel a rise in Zen there. In the same way, the Fall of Constantinople in 1453 helped fuel the Renaissance in the West as refugees from the Eastern Roman Empire brought lost knowledge and know-how to the West. If there was any proof that we’re all connected in some way, look no further.

3 Earlier generations of Buddhist monks like Kukai (founder of Shingon) and Saicho (founder of Tendai) came to China during the Tang Dynasty, when connections to India were still flourishing. Hence, in Kukai’s case, he could study esoteric doctrine and Sanskrit directly from Indian-Buddhist monks. Centuries later, when Dogen and Eisai came to China, Buddhism had declined in India, and had gradually taken root in China in a more Chinese way. Of course, the Dharma is the Dharma, regardless of which culture and time it is taught, but it’s noteworthy that the Buddhism Dogen and Eisai was different: esoteric and scholarly Indian Buddhism had fallen out of favor, and a growing Zen (Chan in Chinese) community had largely replaced them.

You must be logged in to post a comment.