One thing that really annoys me as a long-time Buddhist is the tendency for self-help and spritual seminars to cost so much money. I saw this advertised locally in my area for weeks, and the starting price for a seat is $250 for a backrow seat, which to me is totally bonkers.

The Dharma, as taught by Shakyamuni Buddha was freely given, and required nothing.

Having said that, as a counter to pricey spiritual seminars, I wanted to promote a concept: the Art of Dying.

DYING?!

It is a simple concept: you are going to die. You cannot necessarily choose the hour or manner of your death. But it will occur inevitably occur.

You do not have to take my word for it. Here’s a Buddhist sutra (freely given I might add) from the words of the Buddha:

There is no bargaining with Mortality & his mighty horde.

Whoever lives thus ardently, relentlessly both day & night, has truly had an auspicious day:

So says the Peaceful Sage [Shakyamuni Buddha].

MN 131, translation by Ven. Thanissaro Bhikkhu

The Lotus Sutra, a later Buddhist text but in my opinion the capstone of the Buddhist canon, describes this using the famous Parable of the Burning House in the third chapter. You can find Dr Burton Watson’s translation here (again, for free!).

But, to summarize the Parable, the Buddha Shakyamuni asks us, the reader, to imagine a great, big mansion that’s old, rickey, and so on. Then, imagine the house is burning. Deep inside, some kids are playing in a room, unaware the house is on fire. The father, having just returned from a trip, sees his kids in danger and calls out to them to leave the house at once. The kids, engrossed in their games, fail to see their situation. Finally, the father offers them great rewards if they leave (specifically carts of goods), and the kids finally come out.

The father, Shakyamuni Buddha, has left the burning house and stands outside. He calls to those in danger, namely the “kids”, to see their peril and to come out too.

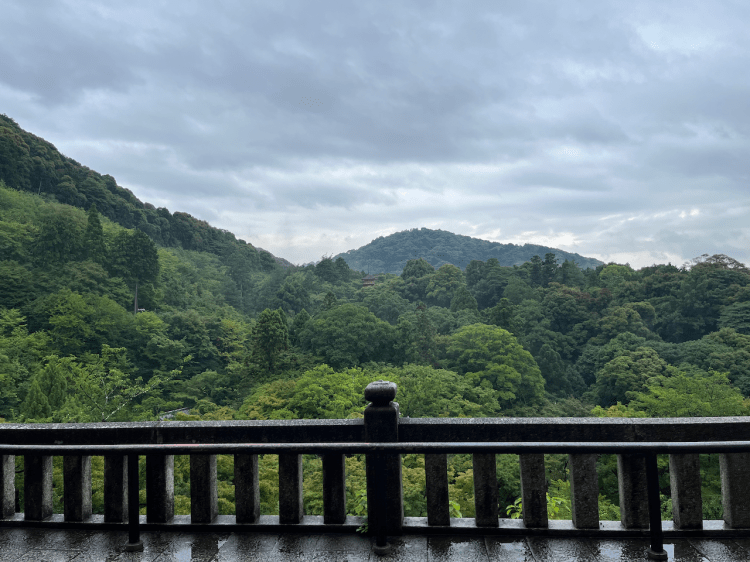

What about the burning house itself? That is the world we live in, with strife, conflict, disease, chaos, aging, and death.

The late Thich Nhat Hanh wrote about this too:

“Imagine two hens about to be slaughtered, but they do not know it. One hen says to the other, “The rice is much tastier than the corn. The corn is slightly off.” She is talking about relative joy. She does not realize that the real joy of this moment is the joy of not being slaughtered, the joy of being alive.”

Thich Nhat Hanh, The Heart of the Buddha’s Teaching

This gets to the heart of the Buddha’s teachings: do not squander the time you have on this Earth. It doesn’t mean you can’t enjoy life and your loved ones, but remember: Death will not wait for it to be convenient for you.

When you hear this, your instinct might be the “live, laugh, and love”, indulge in all the fun things in life before it’s too late. But that’s not what the Buddha intended. When you look back at the Parable of the Burning House, the father wasn’t asking the kids to play more, he was telling them to get out before it’s too late.

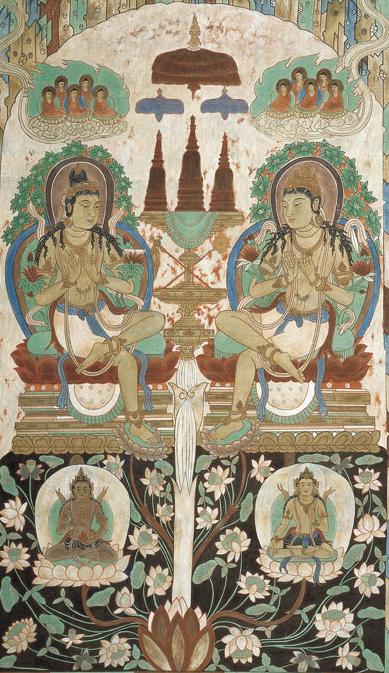

Further, in the Mahayana tradition, one can get themselves out of the burning house, but helping and guide others to get out of the burning house is even better. One can call such people bodhisattvas.

But you can’t help others (let alone yourself) until you :

- Recognize the situation

- Put down your own toys and find the way out before you can help others.

This is part of the progression of the Buddhist path: get your foundations in order, increasing confidence in the Dharma (which you can see in your own life), and turning outward to help other beings.

But starting at the beginning, how does one establish a foundation?

Everyone is different, but generally it starts with some simple things:

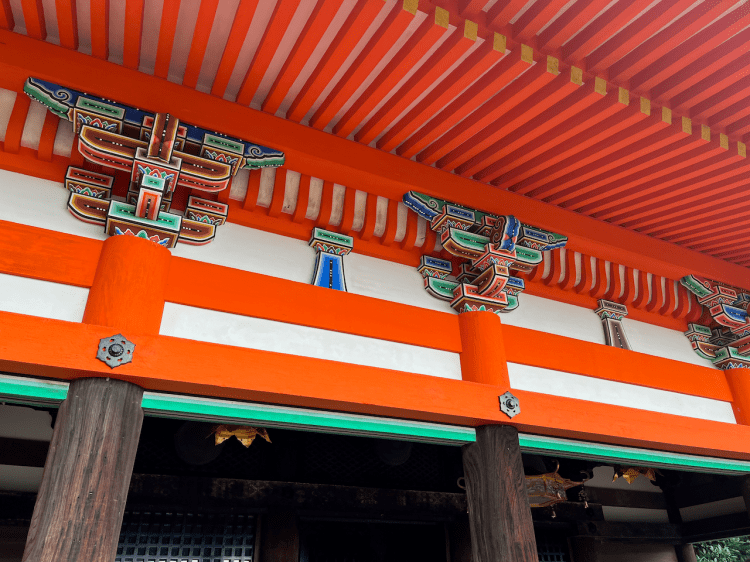

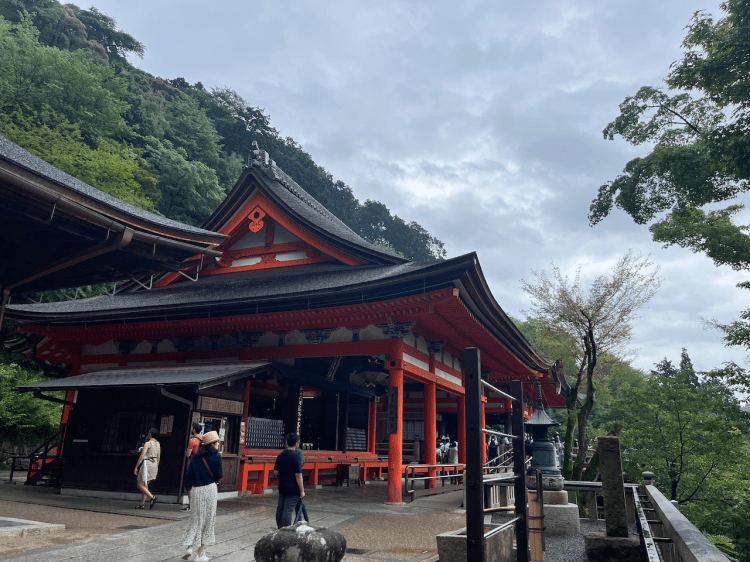

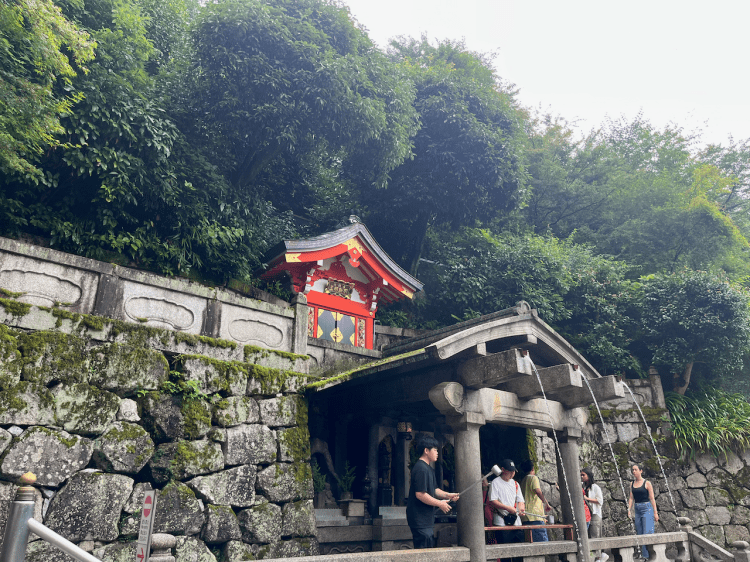

- Taking the Buddha, Dharma and Sangha as one’s chosen refuge (you can do this by yourself or in a community). You can setup a small shrine too.

- Taking up an ethical life, such as undertaking the Five Precepts

- If all five are too hard, start with one, and work your way up over the months and years.

- Cultivate metta:

- Say to yourself (yes, you): May I be well, may I be free from harm.

- Now think of loved ones: may they be well, may they be free from harm.

- Now think of all living beings (even the awful ones): may they be well, may they be free from harm.

- Setup a reasonable daily practice. Think of it like exercise or stretching: if you start too aggressively, you’ll injure yourself and set yourself back. So start small, and build up.

- What does a daily practice look like? Some examples here.

- If all else fails, simply recite the nembutsu.

- A small meditation practice can be beneficial too, but intention matters.

- Study the sutras. Not self-help books, but the sutras. Commentaries on the sutras, such as those provided by Thich Nhat Hanh are quite good and easy to find in used and independent bookstores such as Powell’s City of Books.

- Find worthy teachers and communities, not slick, overpriced seminars or cults. Caveat emptor.

- What does a daily practice look like? Some examples here.

- Give yourself permission to screw up, then reflect on it, and move on.

- Repeat. Buddhism is a long-term practice. “Play the long game“, but also remember you are on the clock. Time is short.

So, that’s your free teaching for today. Thanks for attending this seminar. Want to support the blog? Pay it forward or something. This is “Buddhism on a Budget”, and I strongly feel this is how Buddhism should be.

Namu Shakyamuni Butsu

Namu Amida Butsu

Namu Kanzeon Bosatsu

P.S. apparently this also a band with this name. As fellow PNW residents, I salute them.

You must be logged in to post a comment.