Hello dear readers, I realized recently that after posting I home liturgy examples for Soto Zen, Rinzai Zen, and Tendai sect Buddhism, I had never posted about Jodo Shu sect home liturgy despite being a follower for many years. There are a couple reasons for this.

First, as someone who came to Jodo Shu Buddhism many years ago, I tended to rely on English sources only, and such sources tend follow Honen’s teachings, but nothing beyond that. Thus, through such books I followed Honen’s simple advice that focusing on the nembutsu is all that mattered. So, in my early efforts to learn Buddhist practice, I focused on reciting just the nembutsu. More on why the liturgy has expanded over time later in this post.

The second reason is that the Jodo Shu home liturgy is particularly long. My book on Jodo Shu explains that this usually takes about 20 minutes.

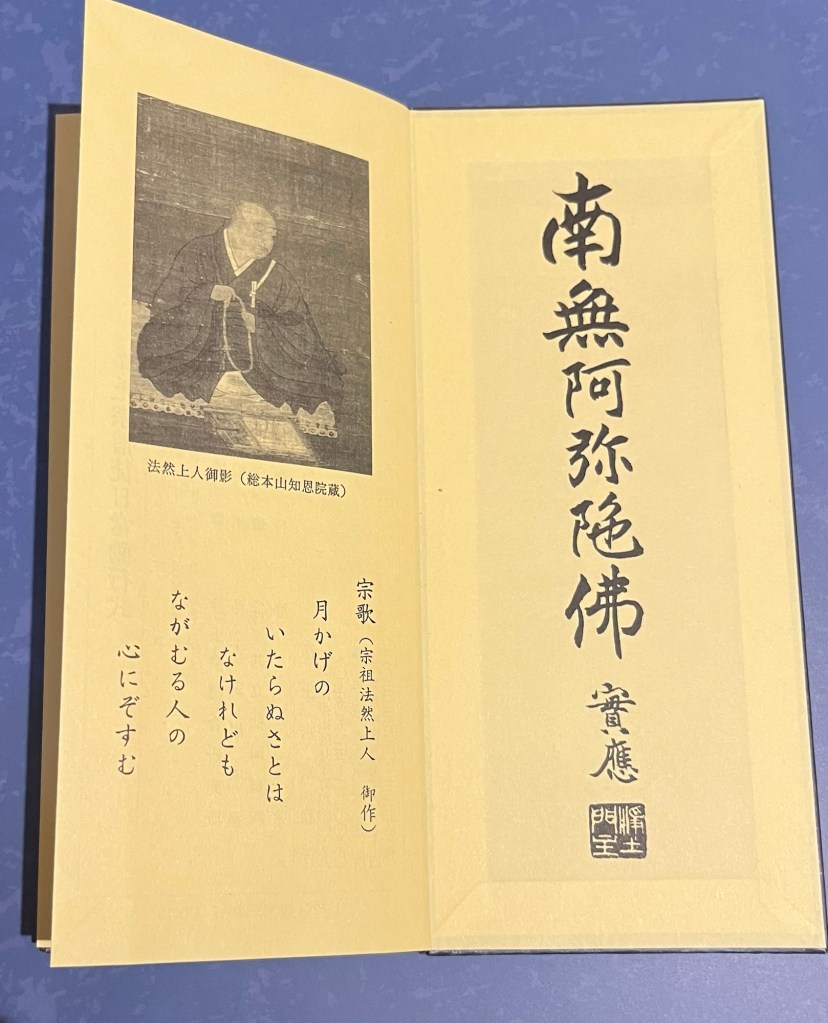

My limited experience confirms this. I have an old Jodo Shu sutra book from many years ago, which I received during one of our earliest family trips to Japan. That particular winter, we celebrated New Year in Japan, I got to participate in a local Joya-no-kané (“ringing of the temple bell”) ceremony, thanks to my father-in-law, and generally had a great time. It might even be the first sutra book I ever owned.

The book, needless to say, has some sentimental value for me.

But I digress.

You can find example Jodo Shu liturgy here on the official Jodo Shu homepage in Japanese. There is even a translated one on the Jodo Shu North American mission website. The format of the liturgy is:

- Kōgé – verse for offering incense

- Sanbōrai – taking refuge in the Buddha, Dharma and Sangha

- Shibujō or Sanbujō – both are verses of praise to the Buddhas

- Sangege – verses of repentance

- Junen – reciting the nembutsu ten times.

- Kaikyōgé – verses for opening the sutra

- Shiseigé – an excerpt of the Sutra on the Buddha of Immeasurable Life, which I posted here.

- Honzeigé – dedicating the good merit to all beings

- Junen – reciting the nembutsu ten times.

- Ichimai-kishōmon – Honen’s One-sheet Document, essentially his last will and testimony.

- (optional) Hotsuganmon – a verse attributed to Chinese Pure Land master Shan-dao, expressing a desire to be reborn in the Pure Land, become a bodhisattva and help others.1

- Shōyakumon – a verse for expressing the light of Amida Buddha.

- Nembutsu-ichi-é – reciting the nembutsu as much as one likes.

- Sō-e-kō-gé – Another verse for transferring the good merit to all beings.

- Junen – reciting the nembutsu ten times.

- Sōgangé – a variation of the Four Bodhisattva vows.

- Sanshōrai or Sanjinrai – three adorations or prostrations toward Amida Buddha

- Sōbutsu-gé – verses of praise to the Buddhas, but also a kind of warm sendoff too.

- Junen – reciting the nembutsu ten times.

As you can see, it has many components, with the nembutsu sprinkled throughout. Many of these verses are very short too, so once you get used to the format, it is not that hard. It can feel a bit daunting upfront if you’re new to Pure Land Buddhism, though.

Thankfully, the Japanese site also has a couple example videos showing slightly different versions of the liturgy. Version one below with uses the Shibujo and Sanshorai:

and version two, which recites the Sanbujo and Sanshinrai instead:

The North America sites uses a little of both: the Sanbujo from version two, and the Sanshorai from version one. By contrast, my sutra book has all the verses, so you presumably pick which version you want to recite. It seems like they are basically interchangeable.

Since there is already an official English translation available online, I won’t repost here. Please refer to the links above for more details.

Instead, I wanted to address the question of liturgy versus just saying the nembutsu, and I found a good explanation in this article.

The author reiterates that Jodo Shu Buddhism begins and ends with the nembutsu and doesn’t need other verses to effect rebirth in the Pure Land. So, pretty consistent so far.

And yet, the author cites Honen who encouraged people to cultivate the “five right practices” (五種正行, goshushōgyō) which includes:

- Recitation of verses

- Observation

- Paying homage

- Reciting the nembutsu [lit. Amida Buddha’s sacred name]

- Praise

Thus as a liturgy, it is meant to cultivate all five, with the nembutsu as the peak or the climax of a movie. From a general Mahayana-Buddhist standpoint, it covers all the important points: taking refuge, repentance, reciting a Buddhist sutra, sharing the good merit, and vows toward becoming a Bodhisattva.

My personal opinion is that if you’re new to Pure Land Buddhism, it’s perfectly fine to just recite the nembutsu, but as you become more comfortable with Buddhism, you can expand to include the whole liturgy. I have no doubt that it’s a wonderful experience once you do it from start-to-finish, but without context it can seem a bit difficult.

In any case, good luck and happy chanting!

1 My sutra book puts the Hotsuganmon at the very end, while the Jodo Shu site in Japanese puts it just after the One Sheet Document. The North America Jodo Shu site doens’t include it at all. I am not sure why there is a difference in format. I assume it is optional.

You must be logged in to post a comment.