I’m still keeping up with the Japanese historical drama the Thirteen Lords of Kamakura, discussed here, which is based primarily on the Azuma Kagami (吾妻鏡) a historical text about the period, and a fascinating look at how the Shogunate, or samurai military government, of the Kamakura Period rose and fell.

The rise of the Kamakura Shogunate began with the climactic battle between the Heiki (Taira) clan and the Genji (Minamoto). In order to topple their rivals, the Genji had to enlist a complex web of alliances with other samurai clans in the eastern regions of Japan, with Kamakura as their capitol, most crucially the Hojo Clan (the source of the Triforce in the Legend of Zelda series). This alliance overwhelmed the Heike and led to downfall.

However, once the Heike were wiped out, and the old Imperial political order ended, the various clans including the Minamoto themselves turned on one another to sort out who the Shogun would be, and would be pulling the strings behind the throne. The first Shogun, Minamoto no Yoritomo, turned on his half brothers and killed them one by one using flimsy legal pretexts, while his firstborn son Yoriie, the second Shogun, vied with his council (the aforementioned 13 Lords above) until he was driven into permanent exile. Hojo Masako, the so-called “Warlord Nun” contended with her father Hojo Tokimasa when he tried to assert a dominant hand, and had him exiled too. As all this was going on, the various allied clans took sides with members of the Hojo and Minamoto. Generation after generation, people kept stabbing each other in the back in order to advance their faction in the new military government.

This left Yoritomo’s younger son, Minamoto no Sanetomo (源 実朝, 1192 – 1219), to assume the position as Shogun, the 3rd in line. Sanetomo was doomed from the beginning.

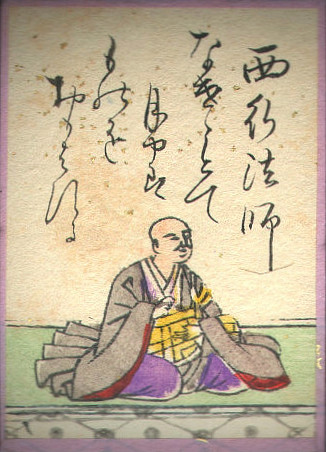

Sanetomo was a puppet of his maternal family, the Hojo Clan, who surrounded him as advisors and ministers, but also carried out the real functions of government. Sanetomo knew from early on that he was essentially a figurehead, and could easily be toppled by whatever faction wanted to replace him with a more amenable candidate for Shogun. It is said that Sanetomo retreated into drinking and composing poetry, of which one of them is included in the Hyakunin Isshu anthology:

| Japanese | Romanization | Translation by Joshua Mostow |

| 世の中は | Yo no naka wa | If only this world |

| つねにもがもな | Tsune ni mo ga mo na | could always remain the same! |

| なぎさこぐ | Nagisa kogu | The sight of them towing |

| あまの小舟の | Ama no obune no | the small boats of the fishermen who row in the tide |

| 綱手かなしも | Tsuna de kanashi mo | is touching indeed! |

Sanetomo evidentially composed the poem after watching some fishermen at work on the shore, envying their simple lives in contrast to the constant political infighting and manipulation that surrounded his.

Sadly, things never got better.

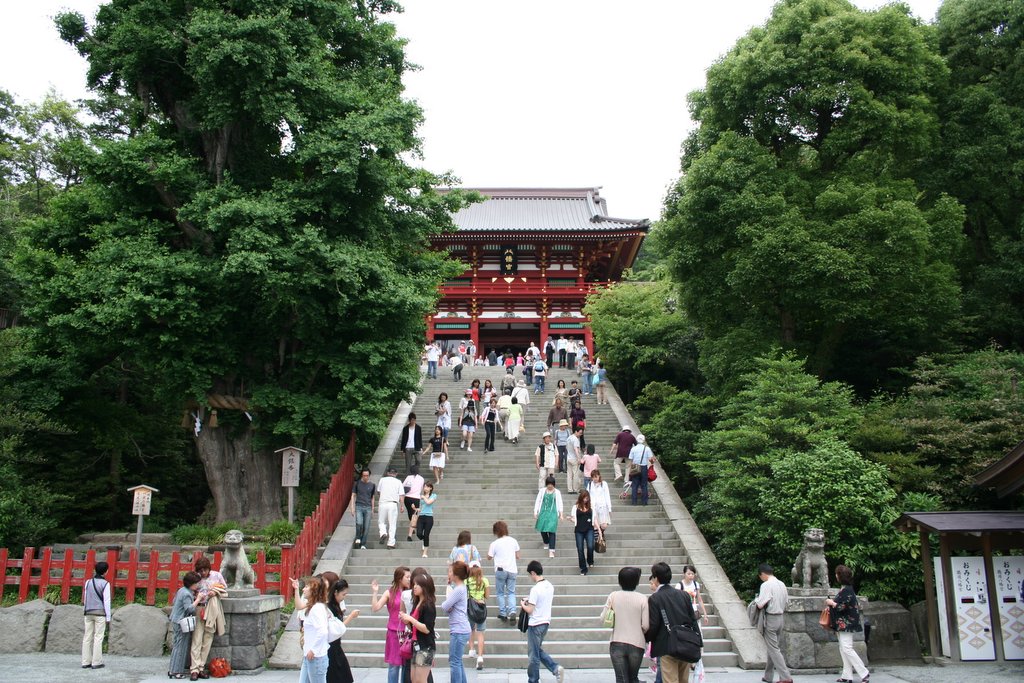

Sanetomo’s life ended at the age of 28, when he was assassinated by his nephew at the footsteps of the famous Tsurugaoka Hachimangu Shrine (visual tour here) in Kamakura. It is said his nephew hid behind the ginkgo tree there, and as Sanetomo descended the steps, leapt out and ran him through with a sword.

Further, the Kamakura Shogunate only spiraled further. With Sanetomo’s death, the Minamoto line ended, and the Hojo Clan promoted various relations of the Minamoto (often drawn from the Fujiwara clan) as the subsequent Shoguns. Each one of these shoguns was simply another figurehead, while the Hojo tightened their grip on power as “regents”. Once Hojo Masako died, there was no one left savvy enough to hold it together, and the Mongol invasions further drained away any remaining resources until the government was finally toppled by a rival warlord.

Sanetomo’s life, the ignominious circumstances that surrounded his family (both his father’s line and his mother’s family’s scheming) ensured that even with the powerful title of Sei-i Taishōgun (征夷大将軍, “Commander-in-Chief of the Expeditionary Force Against the Barbarians”) he lived alone and apart from everyone, constantly in fear of his life, and powerless to do anything about it.

You must be logged in to post a comment.