If political gridlock, government shutdowns due to budget fights, and rabid factionalism get you down, consider the case of the Joseon Dynasty of Korea (1392–1894). The Joseon Dynasty, also known as Joseon-guk in Korean (朝鮮國, 조선국) was the last and longest of royal dynasties of Korea. At 502 years long, it is also among the longest dynasties in world history.

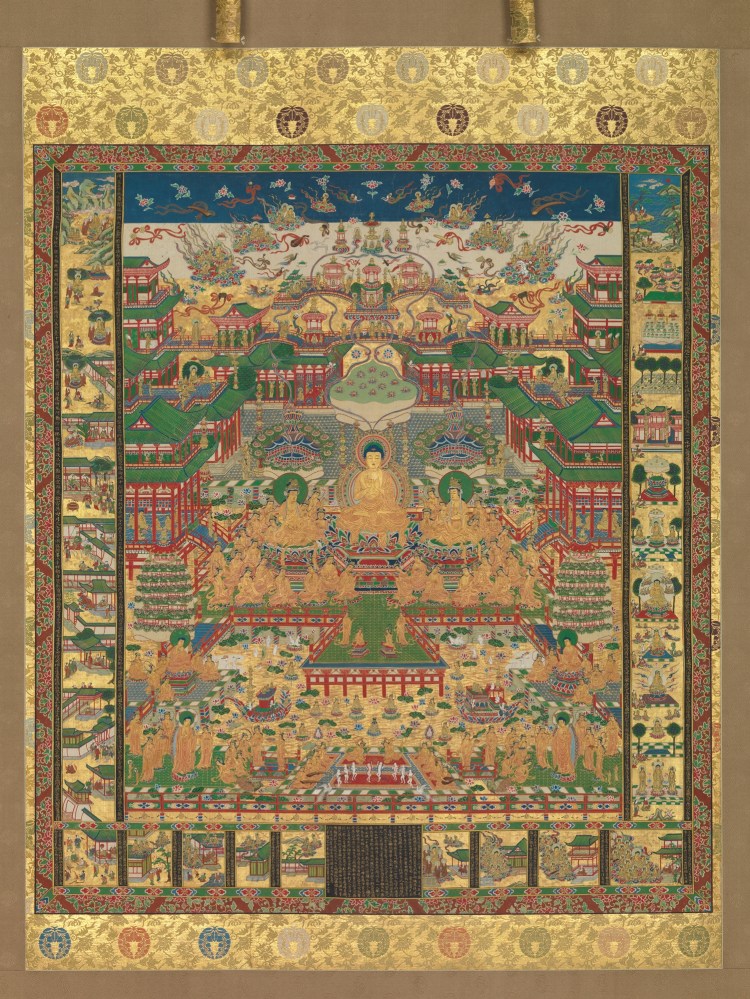

After the rise of Buddhism in East Asia, Confucian teachings took a backseat for a time, until it re-emerged centuries later under a doctrine called Neo-Confucianism. Neo-Confucianism is a fascinating subject all by itself, but it’s a hard one to describe to Western audiences. It’s enough to know that it was an effort to reinforce early Confucian ethics with more philosophy and metaphysics, while avoiding mysticism.

This is important because Neo-Confucianism became the official state doctrine early the foundation the Joseon Dynasty, just as it had become Ming-Dynasty China and Tokugawa-era Japan. Schools of Confucian scholars would staff the elaborate bureaucracies used by each sovereign, and provide advice on policies, or criticism if the sovereign’s conduct was deemed inappropriate or immoral. As the beacon of a rational and orderly society, the sovereign was held to a very high standard, but also (in theory) commanded unwavering loyalty from his subjects. Because orderly and rational societies were valued by Confucian thinking, there was heavy emphasis on ritual, etc. Everyone had their place, and everyone was expected to carry out their moral obligations, putting the needs of society over their own profit.

On paper, this was how it all worked.

In reality, the Confucian bureaucracy (the yangban) of Korea grew very powerful, and different schools of Confucian thought began to compete with one another for dominance in the Joseon bureaucracy. Over generations, these rivalries grew very cutthroat, and worse they splintered into sub-factions, and sub-sub-factions, all vying with one another. Further, sons of bureaucrats had the wealth and resources necessary to ensure they’d pass the civil service exams and become bureaucrats themselves. The Iron Law of Oligarchy comes to mind.

This might seem kind of silly at first glance, since it obviously contradicted basic Confucian ethics.

However, this all began when bureaucrats in the court would debate how to address policy issues at the time, or question certain political appointments. Inevitably reform and conservative wings developed with different views of how to address such issues, and the leading figures of each wing would try to then pack the bureaucracy with their own men.

Is this starting to sound familiar?

The back and forth by factions, starting with the Easterners (dong-in, 동인 or 東人) and Westerners (seo-in, 서인 or 西人) began over subtle ideological disagreements. Then, each of these factions broke up into different factions. The Westerns faction alone broke up into the Noron (노론, 老論) and Soron (소론, 少論) depending on whether you supported Confucian scholar Song Si-yeol‘s reformist policies (the Noron) or not (the Soron). The Easterner faction similarly split up into Buk-in (“northerners”, 북인, 北人) and Nam-in (“southerners”, 남인, 南人) factions.

The king’s response to each of these factions varied by sovereign. In some cases, a king would support one faction over another. But if that faction got too powerful or out of line, the losing faction could sometimes convince the king to purge them from the bureaucracy. Sometimes the purges became extremely violent, with many faction members executed such as the one in 1589.

Inevitably, once a faction was crushed or purged, another would take its place in the court and consoldiate power, requiring yet another purge. By 1545 there had already been four blood purges.

By the time of King Yeongjo (1694 – 1776, 영종, 英宗) the fighting between factions and the bloody purges had gotten so out of hand, that Yeongjo survived an assassination attempt in his youth.

Yeongjo tried to take the high-ground in the conflict, implementing a policy of Tangpyeong (탕평, 蕩平) or “great harmony”. Yeongjo tried to stay above the fray and remained somewhat successful. Barely. By the reign of the next king, his grandson Jeongjo, the bureaucrats were at it again and King Jeongjo fought off a coup by the Noron faction.

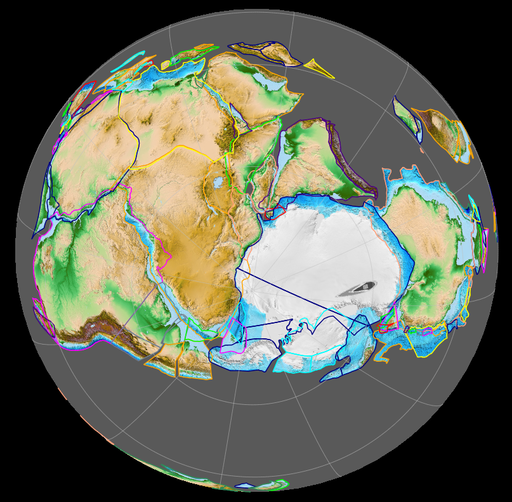

In spite of the coup, the Noron dominates the court after Jeongjo’s later (and mysterious) death until they were ousted for good, but by this time the functions of government were locked in by certain powerful families and from the 1800’s onward the Joseon became isolationist and dysfunctional at a time when Western and Japanese powers grew in strength and aggression. The reforms of 1895 were simply too little too late to save the Dynasty and Korea was annexed by Iapan in 1905.

Much like the Eastern Roman Empire (i.e. the Byzantines), the Joseon Dynasty survived and thrived at times when there was a powerful ruler who could push for reforms, and keep interests in check. But there were always sharks circling the water, and as soon as they smelled weakness there would be bloody infighting and this would reset the clock on any meaningful reforms. Paralyzed by internal strife, other more dynamic, external powers eventually pulled ahead and defeated them.

It also should be noted that were plenty of good, sincere Confucian scholars who made a genuine effort at good governance, such as Kim Yuk, but in the end, powerful men always felt they could do it better when they sensed an opportunity.

P.S. astute readers may have noticed that I keep posting the names using both Hangeul script and Chinese characters (Hanja). Until the modern era, both were used together in a kind of mixed fashion, especially when a person wanted to avoid ambiguity (the Chinese characters are more distinct). Compared to neighbors like Japan or China, Chinese characters were used comparatively less (Hangeul was usually sufficient and simpler), but remain an important part of the language and culture.

You must be logged in to post a comment.