Hello Dear Readers,

The last couple weeks in lockdown (with at least 4 more ahead) have been interesting. After the initial panic, we’ve gradually settled into a routine where keep our kids “in school” during weekdays, take walks a lot in the neighborhood, only visit the grocery store as needed, and generally learn to keep ourselves entertained otherwise.

Being stuck at home a lot does tend to shift priorities. A lot of my personal projects have kind fallen further and further behind, because they just don’t really feel that important anymore.

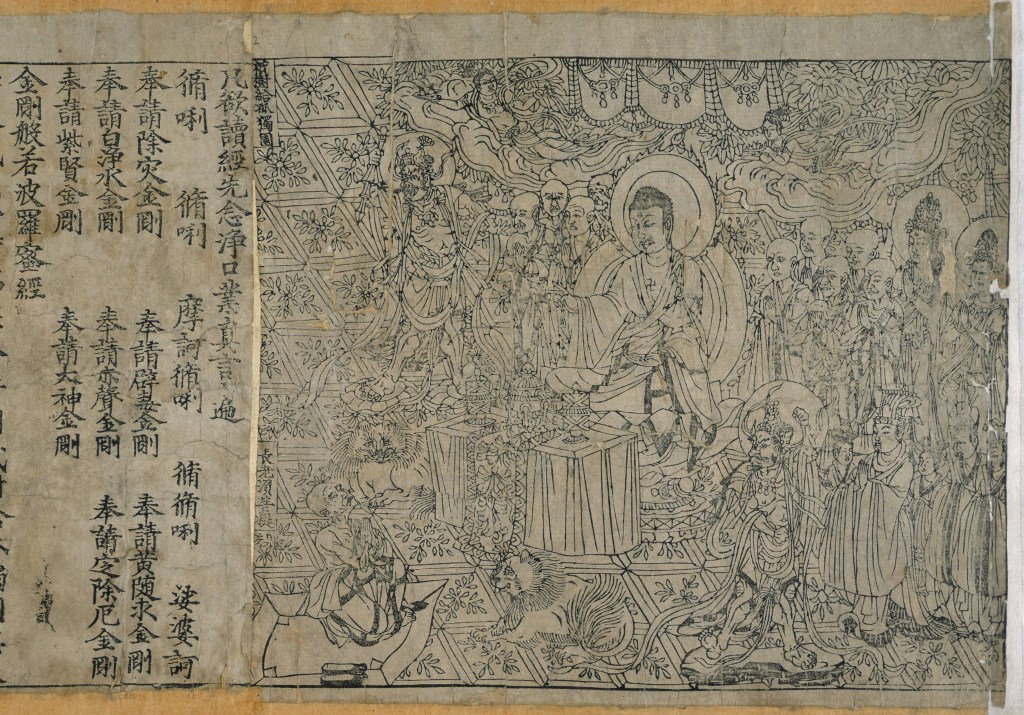

I have caught up on a few books, movies, old episodes of Star Trek: the Next Generation,1 updated the blog (obviously 😏), and been playing Adventurer’s League online with the same community I played with before.2 Things like language study, Buddhist practice, Magic the Gathering and some writing projects have all died on the vine, leaving me with those things which I guess I valued enough to keep up.

All of this takes a backseat to my wife and kids though. Since I don’t work in the office anymore, I can enjoy dinners with them more consistently, and the (mostly) daily walks around the neighborhoods in the warm, spring weather and finally got some things done around the house. This is not to trivialize the danger of the novel Coronavirus, but it’s nice to be able to turn lemons into lemonade sometimes. 😊

In any case, as we’ve settled into a pretty good routine, it’s interesting how trivial some things seem now compared to life before COVID-19, and how others have bubbled to the surface.

It’s fair to say that those of who survive this (and one should never be too confident about one’s own mortality) are going to party like it’s 1999 when this has passed, but at the time, it is going to change our lives. It already has.

1 If you are a Star Trek TNG fan, I highly, highly recommend the new Star Trek: Picard series as well. Season one was terrific. Going back to watch Star Trek: Discovery as well.

2 Happy to see a couple of my more neglected characters in Adventurer’s League finally get some “flight time” and development. Also, it turns out that Eldritch Knights and Land Druids are pretty fun to play. Maybe I’ll post about that soon.

You must be logged in to post a comment.