I intentionally left this post in my blog draft folder for months, but now I am ready to post.

After a small revelation back in early May, I wanted to give it time and ensure that this change in Buddhist path wasn’t a spur of the moment decision.

After that little experience in May, I realized that I had misunderstood Zen Buddhism. Some of this is due to mixed experiences at local (Western) Zen communities,1 and in my opinion, systemic issues with Buddhist publications in English.3 Once I had better access to Japanese-language resources, and based on things I had sort of rediscovered, I decided to try to and go heads down for a few months and do my best to practice Zen as a lay person and parent.

It took a lot of trial and error to get this right. At first, I had a tendency to succumb to self-doubt and start doing zazen meditation longer and longer, but then I would burn out, or have a busy day and skip. So, eventually I forced myself to keep it to five minutes, and I found I was able to sustain the practice more. Also, if I missee a day somehow, I would not punish myself over it.

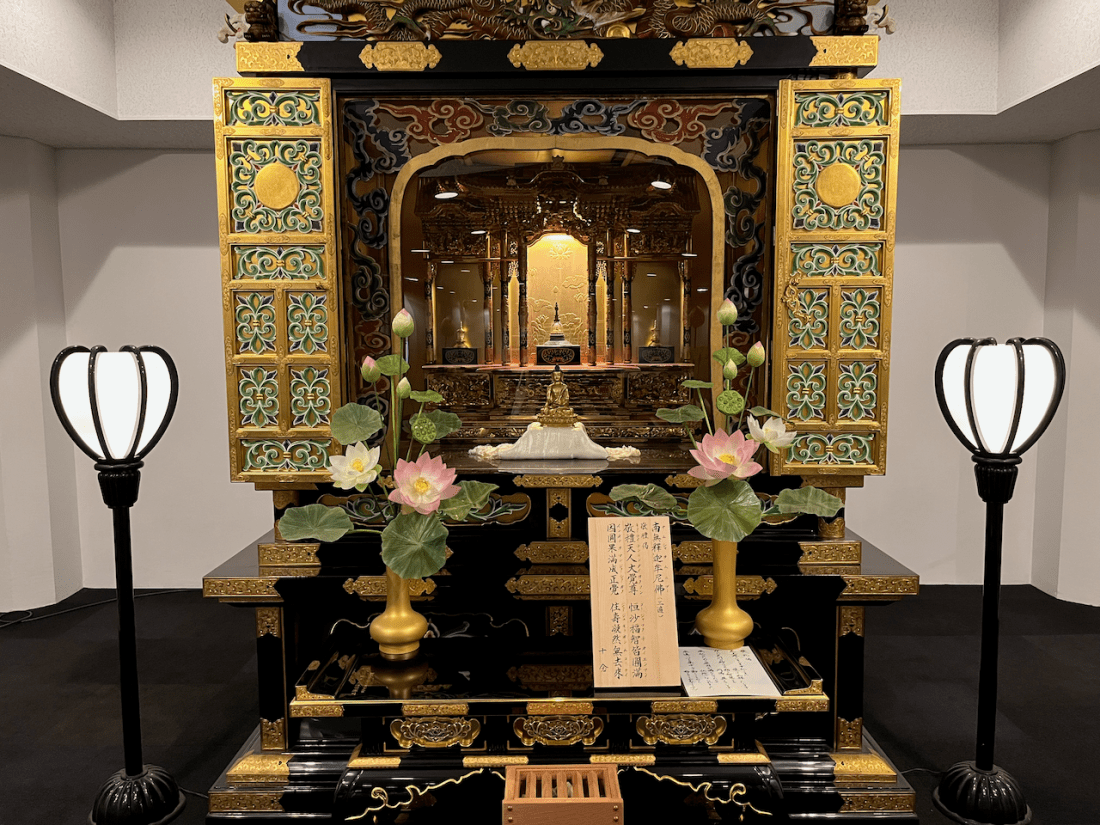

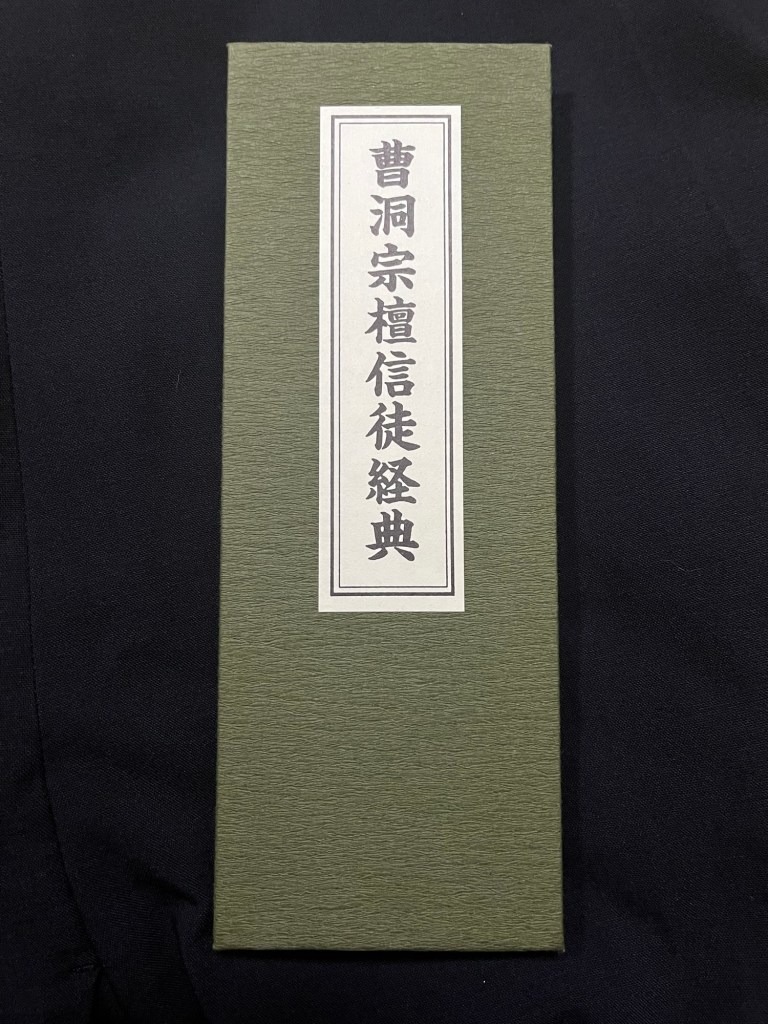

Second, I struggled with how to do a Zen-style home service, so I had to do some research and this led to posts like this and this (these are for my own benefit as much to readers 😏 ). This home service underwent a few updates and changes over time, but I gradually settled on things over time, thanks to an old service I forgot I had.

Finally, I wanted to ensure I focused on Buddhist conduct as a foundational practice, and in particularly by upholding the Ten Bodhisattva Precepts. It’s also emphasized by such past Zen monks as a foundation for other aspects of Zen, but compared to the basic Five Precepts, I found myself struggling both to remember what the Ten Precepts were, and also remembering to avoid things like not bring up the past faults of others, or harboring ill-will towards others. This is still a work in progress, but I assumed it would be. It took me many years of following the Five Precepts before it became second-nature.

Anyhow, since I started this little project four months ago, I am happy to say that I have mostly stuck with it. I can count the days I missed practice on my two hands, which over four months is pretty good. I realized that small, realistic, daily practice is much more effective than trying to focus on big retreats. So, in a sense, it’s been a big win and a learning lesson for myself.

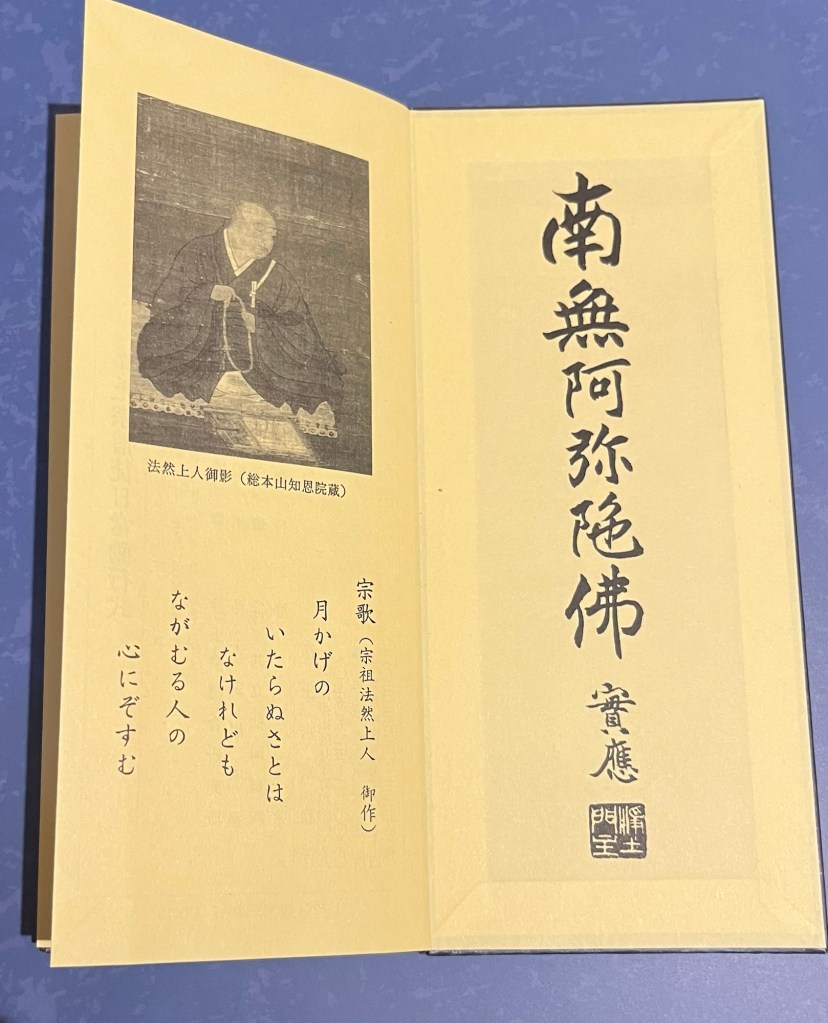

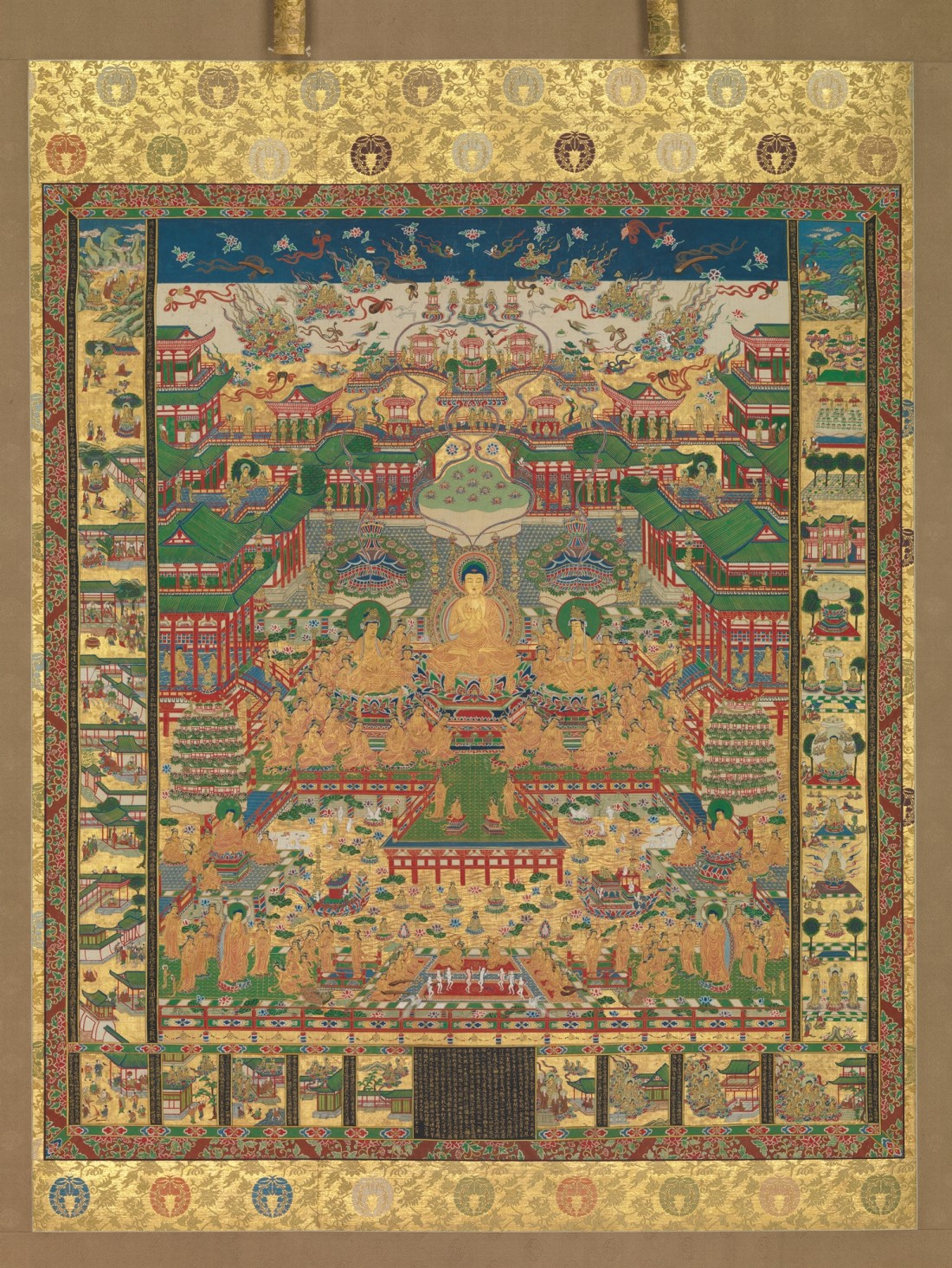

But also I realized that I also really missed some aspects of the Pure Land practice that I had been doing up until this point. For me, I found that Pure Land Buddhism tends to appeal to the heart, while Zen appeals to the mind.

Dr. Janet Wallace: “The heart is not a logical organ.”

Star Trek, “The Deadly Years” (s2ep12), stardate 3479.4

So, my practice has continued to evolve to mostly Rinzai-Zen style practice, but also with a few Pure Land elements too. I suppose this is more inline with mainland Chinese Buddhism where such distinctions are less important than Japanese Buddhism, which tends to be sectarian. Also, if it works for Obaku Zen, it works for me.

So, that’s my update. Am I Zen Buddhist now? I don’t know. I am hesitant to use that label because I am hesitant to associate myself with that community. On the other hand, I’ve found it very beneficial so far, but I haven’t forgotten what I learned from Pure Land Buddhism either. So, I guess I am both, neither, whatever. At this point, taking inspiration from Chinese Buddhism: I uphold the precepts, meditate a bit each day, dedicate merit to loved ones and those suffering in the world, praise Amida Buddha, Shakyamuni Buddha, Kannon and the Lotus Sutra. Whatever label fits that is what I am these days. 🤷🏼♂️

Frankly, I stopped caring. I like how my practice has evolved these past months, and happy to continue.

Namu Shakamuni Butsu

Namu Amida Butsu

Namu Kanzeon Bosatsu

P.S. Posting a little off-schedule, but oh well. Enjoy!

1 Not all experiences have been negative, but I have run into more than a few “Bushido Bros” and Japan nerds2 that soured my experience.

2 Yes, I am a Japan nerd too. I fully admit this, but nerds can be kind of intense and exhausting to talk to, so I don’t like to hang out too much with other Japan nerds.

3 It’s hard to quantify, but English books about Buddhism are either very dry, bland, and scholarly, or read like psychology self-help books, or just too mystical. When I read books in Japanese on similar subjects, I find them more down-to-earth and engaging. I know different people have different preferences, but I don’t like most English publications I find at the local bookstore. It is also why I try to share information (or translate if necessary) whenever I find it.

You must be logged in to post a comment.