Today we explore the final chapter of the 19th-century Soto Zen text called the Shushōgi (修証義, “Meaning of Practice and Verification”), which I introduced here. Chapter five delves into the importance of gratitude in Buddhist practice. You can read chapter four here.

The Buddha mind should be awakened in all sentient beings on this earth through causal relations. Their desire to be born in this world is fulfilled. Why shouldn’t they be grateful to see the Sakyamuni Buddha?

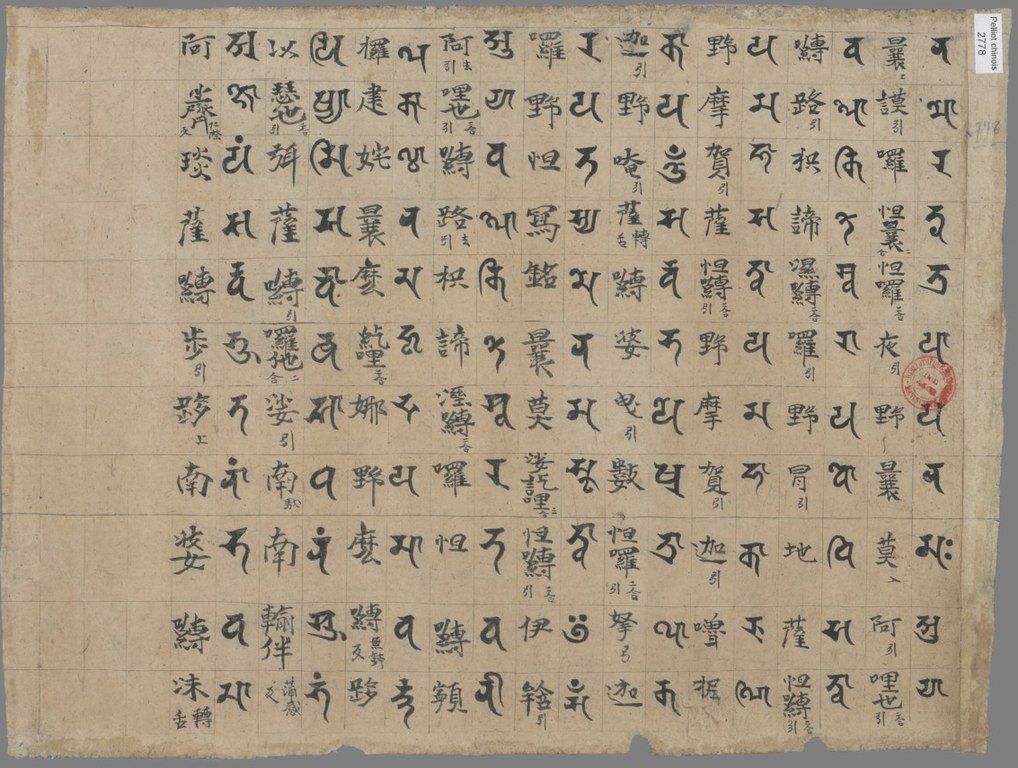

Translation by Soto Zen Text Project of Stanford University, courtesy of Sotozen.net.

Again, reiterating what chapter four said: awakening the Bodhi Mind (a.k.a. the Buddha Mind, etc) is an important part of Mahayana Buddhism.

If the Right Law had not permeated the world, we could not have met it even if we wanted to sacrifice our lives for it. We should quietly reflect on this fact. How fortunate to have been born at this moment when we can meet the Right Law. Remember that the Buddha said: “When you meet a Zen master who teaches the highest wisdom, don’t consider his caste. Don’t pay attention to his appearance, consider his shortcomings, or criticize his practices. In deference to his wisdom, just bow before him and do nothing to worry him.”

The “right law” is a reference to the Dharma of the Buddha. The Dharma always exists, but at times it is obscured, and needs a Buddha to help elucidate it. This is known as “turning the wheel of the Dharma” in Buddhism. Eventually that wheel slows down, another Buddha appears, turns the wheel, repeat cycle.

I am not sure where Dogen is quoting the “when you meet a Zen teacher…” from. I believe the point here is that regardless of who that teacher is, if they are indeed wise, then they are worthy of respect.

Of course, there’s also been plenty of scandals with priests and gurus who abuse their students especially when there’s such a dearth of teachers in the West, with little oversight from faraway parent organizations. So, I hate to say it, but also caveat emptor.

That’s why, personally, I prefer relying less on such teachers and focus on things like devotion, personal conduct, and DIY. In other words, things that don’t require total reliance on a teacher.1 Once these things are established, then it makes sense to reach out and find teachers and communities when you are ready. But, that’s just my opinion.

Anyway, I digress.

We can see the Buddha now and listen to his teachings because of the altruistic Buddhas and patriarchs did not transmit the Law truly, how could it have come down to us today? We should appreciate even a phrase or portion of the Law. How can we help but be thankful for the great compassion of the highest law — the Eye and Treasury of the Right Law? The sick sparrow did not forget the kindness received and returned it with the ring of the three great ministers. Nor did the troubled tortoise forget: it showed its gratitude with the seal of Yofu.2 So if even beasts return thanks, how can man do otherwise?

As we saw in chapter one, the rarity of being reborn as a human, let alone encountering the Dharma is remarkable indeed. In chapter two of the Lotus Sutra there is a verse that reads: If persons with confused and distracted minds should enter a memorial tower and once exclaim, “Hail to the Buddha!” Then all have attained the Buddha way.

Thus, even if one feels like they’re not a particularly good Buddhist, the Lotus Sutra provides hope that even a tiny act here and there still guarantees full one’s progress on the Buddhist path. So, don’t lose heart. Even if you are a half-assed Buddhist (pardon my language), every bit still counts.

To show this gratitude you need no other teachings. Show it in the only real way — by daily practice. Without wasting time we should spend our daily life in selfless activity.

Amen. This isn’t just Dogen’s words by the way. The Pali Canon also teaches a similar message: praise is all well and good, but putting the teachings into practice is an even better way to express gratitude. The trick is learning how to do it in a balanced, sustainable (read: realistic) way. Slow and steady wins the race.

Time flies with more speed than an arrow; life moves on, more transient than dew. By what skillful means can you reinstate a day that has passed. To live one hundred years wastefully is to regret each day and month. Your body becomes filled with sorrow. Although you wander as the servant of the senses during the days and months of a hundred years — if you truly live one day, you not only live a life of a hundred years but save the hundred years of your future life. The life of this one day is the vital life. Your body becomes significant. This life and body deserve love and respect, for through them we can practice the Law and express the power of the Buddha. So true practice of the Law for one day is the seed of all the Buddha and their activities.

Again, as the Lotus Sutra says, even a little practice and conduct goes a long way, even if you can’t see it. Do not sell yourself short. As a thinking, capable human there is much you can do with the time you have.

All the Buddhas are Buddha Sakyamuni himself. Buddhas past, present, and future become the Buddha Sakyamuni on attaining Buddhahood. This mind itself is the Buddha. By awakening to a thorough understanding of this mind, you will truly show your gratitude to the Buddhas.

The phrase “all the Buddhas are Buddha Shakyamuni himself” is, I think, another allusion to the Lotus Sutra. In the Lotus Sutra, Shakyamuni Buddha teaches (in chapter two?) that every Buddha has the same qualities, and also use the same teaching methods to awaken and enlighten others. A similar sentiment is expressed in a Pure Land sutra called the Sutra of Immeasurable Life. In other words, it’s a common theme in Mahayana Buddhism that one Buddha is as good as another, and all have the same qualities.

The “mind is Buddha” comment is a very Zen statement, and I believe it relates to how the mind is a mirror reflecting what it perceives back onto the world (filtered by the mind). Thus an awakened mind sees all as Buddha. I can’t say I know exactly what this means. I am a newbie myself. 😅

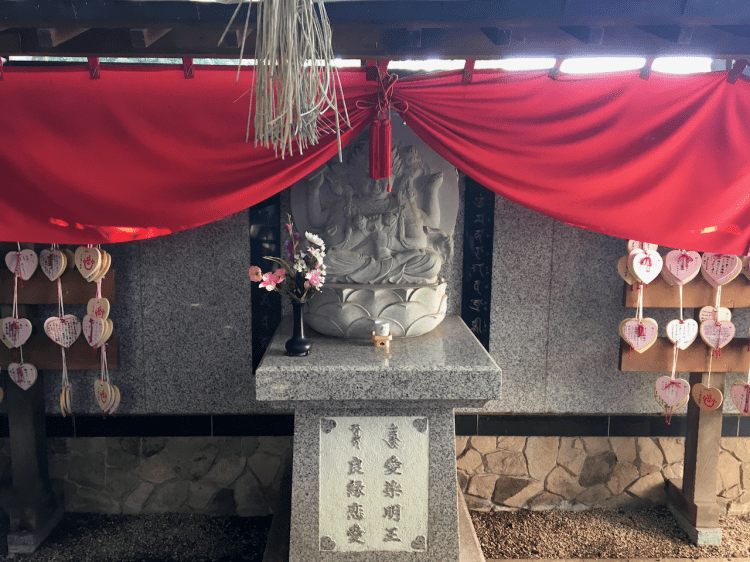

Anyhow, that’s the Shushōgi. For a text that summarizes a much larger and more difficult text in the Soto Zen tradition (Dogen’s Shobogenzo), I think it does a nice job of covering essential points with a coherent theme that is pretty accessible for lay followers. It gets frowned upon by certain Western audiences because meditation is not covered, but I think it’s a great introduction for working-class lay people to the Buddhist path, and provides a foundation that new students to Buddhism can build on through meditation, study, etc. I can see why it has become part of Soto Zen liturgy in Japan.

Further, if you look at other Buddhist traditions in mainland Asia, they will almost certainly teach a similar approach, so Dogen’s teachings, and they way they are expressed in the Shushogi, are very mainstream Mahayana Buddhism in my opinion. Thus, even if you aren’t into Zen, it’s still a perfectly good primer.

Anyhow, if you made it this far, thanks for reading! The Shushogi was a lot of fun to explore, and I personally learned a lot.

P.S. If you want to see how this final chapter is recited traditionally, please enjoy this video:

P.P.S. For those in the US, happy Memorial Day weekend!

1 This is also why I have spent so long following the Pure Land Buddhist path: portable, accessible, and less reliance on gurus and teachers.

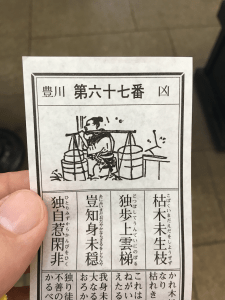

2 I spent hours trying to figure out what this alluded to, but with a bit of determination and luck (and some Google translate 😅 of Chinese Wikipedia), I got my answer.

In a Chinese-historical text called the Book of Jin, there is a story about a man named Kong Yu (孔愉, 268 — 342), courtesy name Jing-Kang (敬康). Kong Yu (Japanese pronunciation Kōyu) once was walking through a region called Yubuting, when he saw a turtle being sold at a roadside market for food. Kong Yu bought the turtle and set it free so that it would not be eaten. The turtle turned left and went to the river. Later, when Kong Yu was appointed governor of Yubuting, he was granted an official seal in the shape of a turtle, which mysteriously faced left. Kong Yu realized that this seal of governance was somehow repayment by the turtle for his kindness. In Japanese the seal is called yofutei (余不亭), and the story is called kyūkame yofuin (窮亀余不印, “Seal of the Distressed Turtle”).

You must be logged in to post a comment.