Having travelled in a westerly direction for a long time, and finally turning south at Samarkand, the 8th century Buddhist monk Xuan-zang is finally approaches the hinterlands of India, birthplace of the Buddha.

Previous episodes:

- Prologue

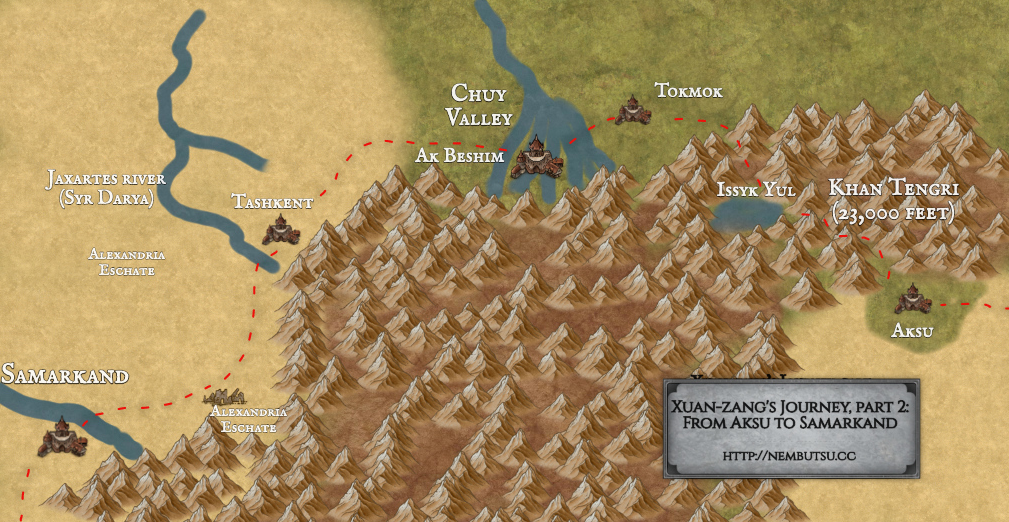

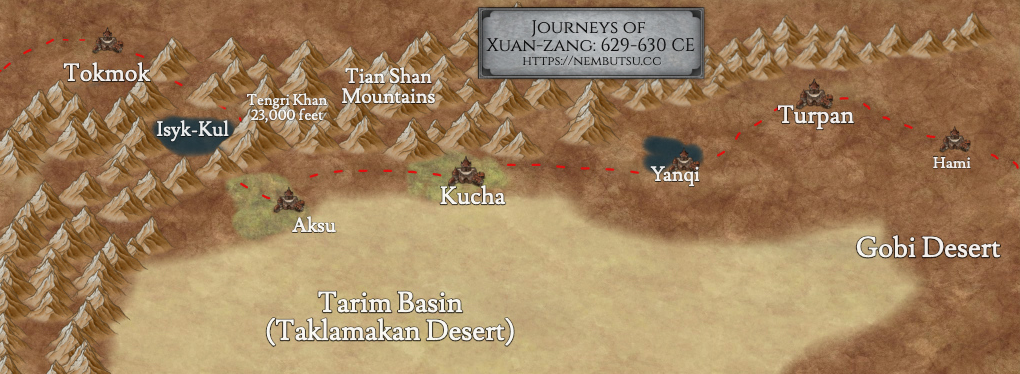

- Part 1 – Northern Silk Road

- Part 2 – Over the Tian Shan mountains

- Part 3 – Western Khaganate

- Part 4 – Southward

In our last episode, Xuan-zang had gone as far as the city of Balkh (modern Afghanistan) and was deep in “Buddhist country” northwest of India. Times are very different now, but it was a major bastion of Buddhist learning at the time. From here, Xuan-zang moves to Bamiyan and the famous statues there.

Journey to Bamiyan

While staying in Balkh (part 4), Xuan-zang befriended a local monk named Prajñakara. Prajñakara was, according to Xuan-zang, a follower of Hinayana Buddhism (instead of Mayahana Buddhism), and yet Xuan-zang respected him so much they decided to journey the next leg together to India: Bamiyan.

These two besties, along with their caravan, had to traverse the Hindu Kush mountains to reach Bamiyan.

Not unlike the crossing of the Tian Shan mountains (part 2), the overload route was extremely dangerous. Xuan-zang reported snow drifts up to 20-30 feet tall, and the weather was a constant blizzard:

These mountains are lofty and their defiles deep, with peaks and precipices fraught with peril. Wind and snow alternate incessantly and at midsummer it is still cold. Piled up snow fils the valleys and the mountain tracks are hard to follow. There are gods of the mountains and impish sprites which in their anger send forth monstrous apparitions, and the mountains are infested by troops of robbers who make murder their occupation.

page 45, The Silk Road Journey with Xuanzang by Sally Hovey Wriggins

Thankfully the more experienced Xuan-zang and his team crossed safely and with fewer casualties than past mountain crossings. In time they reached Bamiyan (بامیان in Dari language).

Bamiyan and the Great Buddhas

Bamiyan, since antiquity, has been an oasis town residing where the Hindu Kush and Koh-i-Baba mountain ranges meet, and is a high-altitude, cold-desert climate. Nonetheless, Xuan-zang described Bamiyan as producing wheat, fruit and flowers, as well as pasturage for cattle and such. Due to the climate, Xuan-zang stated that people wore fur and coarse wool, and their personality was similarly coarse and uncultivated. Yet he praised their sincere religious faith.

Up until 2001, the town of Bamiyan was dominated by several sites, including two massive Buddha statues which were built during the reign of the so-called “White Huns” or Hephathalites. The Huns themselves were not Buddhist, but allowed Buddhist worship to continue and devout local patrons helped fund the statues perhaps as an act of piety. Interspersed between the statues were monasteries and grottoes carved into the cliffside.

Of the two “great Buddha” statues, the “eastern” statue depicts Shakyamuni Buddha, the historical founder, measuring 38-meters, while the western statue depicts Vairocana Buddha1 measuring 55-meters. Sadly these no longer exist, as they were destroyed by the Taliban in 2001. In Xuanzang’s time, the status were painted and decorated. The western statue was painted red, while the eastern was white. Both had blue-orange robes, and adorned with gold. This coloration lasted at least until the 12th century.

Interestingly, Xuan-zang described a third, reclining statue of the Buddha at Bamiyan, but no evidence has been found yet of this statue.

In any case, Xuan-zang was greeted by the king of Bamiyan and the local monks, adherents to an obscure sect of “Hinayana Buddhism” that taught that the Buddhas transcended “earthly laws”, took Xuan-zang and his party on a tour of the monastery and valley. My book and online research doesn’t clarify which sect or what this means.

Despite the warm reception, it doesn’t appear that Xuan-zang stayed all that long, and eventually moved on through the Hindu-Kush mountains to Kapisi next.

Kapisi and the Chinese Prince

Next through the Hindu Kush mountains was the city of Kapisi (also known as Kapisa, Chinese: 迦畢試 Jiapishi), which was the capitol of the local Kapisi Kingdom near the modern city of Bagram. Xuan-zang reports that once again, the weather was very difficult, and they even got lost at one point, but some locals helped guide them safely to Kapisi.

As with Bamiyan, Xuan-zang received a cold reception from the people, but was greeted by the local king whom he described as “intelligent and courageous”, and ruled over the neighboring areas.

Bamiyan and Kapisi are both places that have seen countless historical events. Alexander the Greats army marched through Kapisi in the spring of 329 BCE, and the Kushan Empire established Kapisi at its first capital in the first century CE. It was the Kushans in particular who were instrumental in helping Buddhism spread to East Asia (and now the world) especially under the great Emperor Kanishka (reigned 127 – 150 CE).

During the reign of Kanishka, a Chinese prince had resided in a monastery in Kapisi as a political hostage. When the prince returned home, he sent gifts and offerings to the monastery in gratitude. Centuries later during the 7th century CE, Xuan-zang paid homage to this prince at the monastery (called the “Hostage Monastery”), where it as thought that the prince’s treasure was buried. According to Xuan-zang’s account, he suggested they dig under a statue of the Buddhist deity Vaiśravaṇa,2 and after a time, the treasure was discovered. Because Xuan-zang was also Chinese, like the prince, it was assumed that his fellow countrymen from the past helped guide them to the treasure.

Later, Xuan-zang was invited by the king of Kapisi to preside over a religious debate amongst the Buddhist clergy, and (again based on Xuan-zang’s account) he was well-versed in the Buddhist doctrines and won, while his opponents only knew their own limited doctrine. One cannot help but roll their eyes slightly. 🙄

Finally, Xuan-zang ran into Hindu ascetics for the first time. Hinduism as we know it, arose roughly the same time as Buddhism and developed in parallel, not one from the other. A common and incorrect statement is that Buddhism descended from Hinduism; they drew from the same cultural and religious well, but arrived at different conclusions. At this time in history, Hinduism was on the rise as Buddhism began a slow decline. Since Hinduism had never reached China, Xuan-zang was not aware of it and spoke ill of the ascetics he encountered, describing them as decadent, untrustworthy, and selfish. It’s unclear why he had such a negative first impression though. Later, in India, he would invest much time debating against them in philosophical contests.

However, Xuan-zang’s joruney was not done. He needed to reach the next destination before crossing into India: Jalalabad.

…. which we’ll talk about in our next post. Thanks for reading!

1 Vairocana is a “cosmic Buddha” that first appears in a Mahayana version of the “Brahma Net Sutra” (the Pali Canon/Theravada version is unrelated). Vairocana, the “Buddha of the Sun” is also the great Buddha statue at Nara, Japan, and is particularly important in the esoteric Buddhist tradition where it is called Maha-Vairocana.

2 Vaiśravaṇa, known in Japanese Buddhism as Bishamonten (毘沙門天), can be seen at the famous temple of Todaiji in Nara. I took this photo back in 2010 when visiting there.

Indeed, what we see today of Buddhism in Japan and beyond is directly related to the things that Xuan-zang saw along the Silk Road, even if the connection is not obvious at first sight.

You must be logged in to post a comment.