Hello Dear Readers,

This is another reference post. I noticed that one of my most popular posts is the entry on a Buddhist chant called the Mantra of Light, and there’s multiple ways to read and recite it depending on what language you choose. Anyhow, it made me realize that there’s a big knowledge gap about Sanskrit in a specifically Buddhist context. There’s plenty of Sanskrit language resources out there, but they’re focused on Hinduism, and Hindu-related literature. Even the writing system used in language textbooks, Devanagari, tends to assume certain things.

Sanskrit is a language that’s used in a variety of contexts, and religious traditions, including Buddhism, especially Mahayana Buddhism.

As a language, it is way too big to cover in this blog, and I am just a novice, but I wanted to provide some real, fundamental basics of how Sanskrit works, with an emphasis on Buddhism.

What is Sanskrit?

Sanskrit is a very old language still widely used in some contexts. It is related to Greek and Latin, among other things, but mostly as a distant cousin. The Arya people who come into northwest India spoke it natively, and then as they took over north India, they imposed their language on people there.

Just as Latin eventually morphed into languages like Spanish, French, and Italian (among others), or influenced languages such as English, German or Russian, Sanskrit followed a similar trajectory. Languages descended from Sanskrit are called Prakrits. Prakrits were the colloquial forms of Sanskrit, each with regional differences, while Sanskrit remained the “high” language, increasingly relegated to things like religious ceremonies or literature.

Why Sanskrit and Buddhism?

The historical Buddha, Shakyamuni, did not use Sanskrit when teaching his disciples. His native language was probably Magadhi (still spoken today), but he often used Pāli when speaking to others since it was so widely known. Both Magadhi and Pāli are prakrits, descended from Sanskrit.

Since Pāli was such a popular language, it was how most early Buddhist sermons were memorized and passed down to future generations. Some Buddhist traditions, especially Theravada Buddhism, preserve these sermons using Pāli.

However, as Buddhism spread northward along the Silk Road, it was recorded in yet more prakrits such as Gandhari (Pakistan area), and such, not Pāli. By this point, there were Buddhist texts preserved in all sorts of local prakrits, not necessarily Pāli, and it probably became unmanageable.

The early Mahayana Buddhists started converting texts and teachings to Sanskrit instead. While Sanskrit wasn’t a common, spoken language, it was something that everyone more or less knew, just as medieval writers in Europe all knew at least some Latin. Thus as the layers of literature built up over time, and especially outside the core areas of India, it made more and more sense to just use Sanskrit for everything. Their Sanskrit wasn’t always “pure” Sanskrit, but it was good enough.

The featured image above is of the temple of Sensoji, better known as Asakusa Temple, in Tokyo, Japan. The central altar has the Sanskrit letter “sa” for satyam (truth) prominently displayed using Siddham script. Thus, even in a place like Japan, Sanskrit is still being used.

What Writing System Does Sanskrit Use?

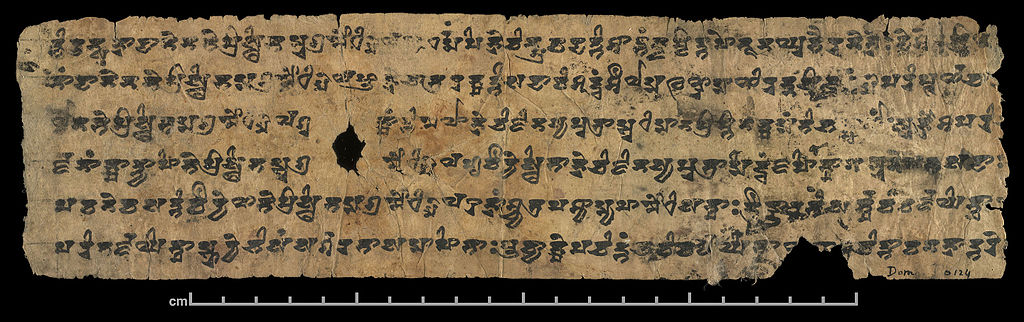

This is a surprisingly hard question to answer. Unlike some languages, like Greek or Chinese, it had no fixed writing system. Every knew at least some Sanskrit, but everyone wrote it down in their own way. The Pillars of Ashoka used the Brahmi script to convey Buddhist teachings to the masses, while Buddhist texts on the Silk Road were often recorded in Karoshthi, and Buddhist mantras were recorded in Siddham.

So, what writing system should Sanskrit be written in? Whatever conveys it best to the reader.

For the purposes of this blog article, we’ll stick with the Roman Alphabet, with extended diacritics. For Buddhists, there is no benefit to using modern Devanagari, since early Buddhists didn’t even use it, and it’s just an extra layer to learn. Just don’t bother. The Roman Alphabet is sufficient for Western audiences.

Sanskrit Alphabet

The Sanskrit alphabet (regardless of what script you use) is broader than English because each sound has its own letter (sometimes two), and thanks to the grammarian Pāṇini, it’s all carefully organized in a sensible system.

Many of these sounds exist in English, but do not have their own letter to distinguish them; we just pronounce them automatically. Some sounds definitely do not exist in English and require extra care.

| voiceless | voiced | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| open | ḥ | h | ṃ | a | ā | ||||||

| velar | k | kh | g | gh | ṅ | ||||||

| palatal | ś | c | ch | j | jh | ñ | y | i | ī | e | ai |

| retroflex | ṣ | ṭ | ṭh | ḍ | ḍh | ṇ | r | ṛ | ṝ | ||

| dental | s | t | th | d | dh | n | l | ḷ | |||

| labial | p | ph | b | bh | m | v | u | ū | o | au | |

| consonants | vowels | ||||||||||

We can’t cover all these letters in detail here, especially pronunciation. There are some excellent pronunciation guides like the video series below. While it’s a Hare Krishna channel, not a Buddhist one, the explanations are excellent and clear.

A notes worth calling out here though:

- ḥ – this is like a “breathy” h-sound that shows up at the end of certain words.

- ṃ – although it looks like an “m”, it sounds more like an “ng” sound as in running. In the Buddhist tradition of praising the three treasures, the phrase Buddhaṃ Saranaṃ Gacchāmi, it is pronounced like “boo-dang” not “boo-dam”.

- Sanskrit distinguishes between letters like k and kh, g and gh, d and dh and so on. These are separate letters in Sanskrit. Letters with an “h” are pronounced with a puff of air. Think of the English word redhead. That’s a fairly close analogy to “dh”. Similarly, egghead, for “gh”, dickhead for “kh” and so on. Not very civilized, but it works. 😆. Thus, Buddha, can be broken down to letters bu-d-dh-a, where “dh” sounds like redhead.

- Side note: the ph in Sanskrit is not an “f” sound. This confused me a lot when I looked at works like “phalam” (fruit). It’s a breathier “p” sound.

- ś and ṣ are both like the English sound “sh”. A common example in Buddhism is the word Śastra, which is a kind of important treatise. This is pronounced like “shastra”, not “sastra”. I am not 100% sure how ś and ṣ differ, but for practical purposes they’re more or less the same.

- ñ – Just like Spanish in words like El Niño.

- The letters ṭ, ṭh, ḍ, ḍh and ṇ (the ones with a dot beneath them) are extra difficult to pronounce for English speakers since we don’t really have “retroflex” sounds (sounds where the tongue touches the roof of the mouth). Thankfully these don’t come up too often in Buddhist Sanskrit.

- r – a nice rolled “r” sound like in Spanish, Latin, etc, not the American “r” sound.

- v – This one is confusing, but the “v” is actually pronounced like a “w” sound. The aforementioned “Bodhisattva” is correctly pronounced like “Bodhisattwa”.

This not a complete summary, but will hopefully address some pitfalls. Let’s look at vowels too.

Vowels in Sanskrit are fairly straightforward, but with a few caveats worth noting:

- Sanskrit vowels are distinguished by “short” and “long” sounds. As with the consonants, each one has its own letter to distinguish it, unlike English “o” which can be pronounced multiple ways. The video series I linked above shows vowel pronunciations as well. Just remembere that long and short vowels might look similar in the Roman alphabet, but they are distinct letters.

- a is the default sound that’s used when there is no other vowel explicitly used. It sounds like “uh” as in “duh” not as in “father”; that’s the letter ā instead.

- Sanskrit has a vowel ṛ that doesn’t really exist in English. Imagine the English word “rip”, remove the ending “p” and roll the “r”. That’s ṛ. Even the Sanskirt word for Sanskrit, saṃskṛta, uses ṛ instead of an i. Usually in English people transliterate this as “ri” instead of “ṛ”, but be aware that this is its own vowel. Also note that r is a consonant, and ṛ is a vowel. They are not the same.

- The au sound is like English “ow”, not “aw”. Imagine hitting your head on the door-frame. That’s “au”.

- The ai sound like the same as “yipe!”. Imagine touching a hot pan. That’s the “ai!” sound.

A Note on Pronunciation

The reality is is that, like Latin, there are few, if any native speakers today. Many people in India, and even abroad, learn Sanskrit (and for good reason), but each person colors their Sanskrit pronunciation with their own native language. That’s ok. It’s normal. So, nobody today pronounces it perfectly.

That said, even knowing a few basics rules, like the ones I highlighted above, will go a long way to really appreciating how beautiful Sanskrit is, and when reciting Buddhist mantras or prayers, it really brings them to life. Give it a try!

But also don’t worry: the Sanskrit Police will not arrest you if you make a mistake.

Sandhi Rules

Every language has at least some rules where sounds blend together or change sightly to make things smoother. Some languages have more rules than others. Sanskrit has a lot. These are called “Sandhi” rules (the grammatical term “sandhi” even comes from Sanskrit). While Sandhi rules for Sanskrit are a huge pain to learn, they are super important for making sense of Sanskrit, including Buddhist Sanskrit. Why? Let’s look at an example below.

The nembutsu, which I have discussed many many times in this blog, is sometimes written in Sanskrit as:

namo’mitābhabuddhāya

This phrase is long, and actually comprises of three words blended together, using Sandhi rules to further smooth things out.

- namaḥ – praise, especially reverent praise toward another

- amitābha – Amitabha Buddha

- buddhāya – Buddha, but with a dative-case ending: to the Buddha. We’ll get to conjugation soon.

Glomming words together like this is common in Sanskrit, and the Sandhi rules help “glue” them together. Of particular note is the final aḥ in the first word, followed by a vowel. According to Sandhi rules (very handy chart here), aḥ + vowel sound changes to o. So, namaḥ + amitābha becomes namo‘mitābha. The apostrophe is a visual tool to help with readability.

For Avalokiteśvara, the famous bodhisattva, if we were to praise them, the same Sandhi rule would apply: namo‘valokiteśvara.

On the other hand, if we were to praise Śariputra, the Buddha’s important monastic disciple, then according to Sandhi rules aḥ + ś would not actually change and simply be namaḥ śariputra written as two words.

Similarly, if a bunch of Buddhas (buddhāḥ) were going somewhere (gacchanti), the Sandhi rules would simply drop the ḥ: buddhā gacchanti

Anyhow, these are pretty basic examples, but Sandhi rules get complicated, and memorizing the entire Sandhi chart isn’t necessary for most people. The important thing to understand is that when two words abut one another, the final sound of the first word, and initial sound of the second often blend together to make pronunciation smoother. Further, Sanskrit often strings multiple words together in written form.

Conjugation

If you ever dealt with noun declensions in classic languages like Latin and Greek, guess what? Sanskrit has them too. Since they are distant cousins, this isn’t really all that surprising.

Modern languages have comparatively fewer conjugations because over the centuries languages become smoother and more streamlined. Modern Indian languages based off Sanskrit such as Hindi, Gujarati, and Bengali are relatively simple to learn, while Romance languages like Spanish, French and Italian are streamlined versions of Latin. In the same way, modern Greek is a simpler, more streamlined version of classic Koine Greek, which itself was a simpler, more standardized form of ancient dialects such as Homeric Greek.

Older Indo-European languages often had complicated conjugation and inflection systems, and since Sanskrit is among the oldest, it’s inflection system is quite complex.

Like every language, Sanskrit has to describe who does what to whom, and with what. Languages like English usually use prepositions like “to”, “from”, “with”, etc. Japanese and Korean uses particles. Sanskrit, Latin, and Greek use inflected endings. For example, let’s look at the word Buddha:

- buddhaḥ , usually just written as buddha – this is the nominative form (e.g. “the Buddha”).

- buddham, this is the accusative form (e.g. a verb does something to the Buddha)

- buddhāya – this is the dative form meaning “to” or “for” someone. Or for indirect objects. (e.g. we give a direct object to the Buddha)

- buddheṇa, this is the instrumental form (e.g. “with the Buddha”)

- buddhe, this is the locative form (e.g. “on the Buddha”)

- buddhāt, this is the ablative form (e.g. “away from the Buddha”)

And so on. You can convey a lot with inflection in just one word, but the drawback is that the rules are complicated to learn.

Further, Sanskrit divides nouns into the following declensions:

- Masculine nouns with “a” endings – Buddhaḥ, bodhisattva, nṛpaḥ (king), etc.

- Neuter nouns with “a” endings, satyam (truth), vanam (forest), śāstram (a Buddhist treatise)

- Feminine nouns with “ā” endings – adityā (sun)

- Feminine nouns with “ī” endings – bhikṣunī (a buddhist nun), nadī (river)

- Masculine, neuter, and feminine “u” endings – bhikṣhu (a buddhist monk), Vasubandhu (the famous monk), dhenu (cow)

- Masculine, neuter, and feminine “i” endings – Bodhi (wisdom), agniḥ (fire)

- Nouns with “ṛ” endings – pitṛ (father), mātṛ (mother)

In short, it’s a lot. There are 12 different categories of noun declensions (Latin had 5, iirc, or slightly more if you count things like masculine first declension, etc).

Note that “grammatical gender” is not always the same as the actual gender of an object. It’s just how nouns are organized. The word for sun is “feminine”, but moon is “masculine”. There’s usually no logic to which gender a word fits, it is just what category it happens to fit.

Conclusion

Knowing Sanskrit is not required to be a devout Buddhist. Buddhism doesn’t really rely on the notion of a “holy language”, so Sanskrit is just as good as Pāli, which is just as good as Classical Chinese (a frequently underrated language), which is just as good as Korean, Japanese, English, French, Ukrainian, etc.

But Mahayana Buddhism does owe much to Sanskrit due to how the tradition grew and then consolidated along the Silk Road before coming to China. Thus, knowing even a little bit of Sanskrit is a really nice way to connect with the past, and appreciate what we’ve inherited thus far.

This page is pretty unpolished, and probably has a few errors, but I hope you find it useful.

Namo’mitābhabuddhāya

Edit: Somehow my blog app kept re-posting an old draft, making publishing difficult. This should all be cleaned up now, and other typos have been corrected as well.

You must be logged in to post a comment.