With the conclusion of the hit mini-series Shogun,1 it seemed like good time to delve into what a Shogun was. I talked a lot about the first few Shoguns of the Kamakura Period, and the Shoguns of the late Edo Period, but there’s a lot more to the story.

In early Japanese history (a.k.a. Japanese antiquity), the government was modeled on a Chinese-style, Confucian-influenced bureaucracy. This is epitomized in the Ritsuryo Code which started in 645, under the Taika Reforms, and continued (nominally) in some form all the way until 1868.

This imperial bureaucracy elevated the Emperor of Japan to the first rank, and other officials and nobility were allocated ranks below this. The ranks dictated all kinds of things: salaries, colors to wear at the Court, other rights and responsibilities, etc. There were bureaucratic offices for all sorts of government functions: land management, taxes, religious functions, military and so on.

The imperial court did not rule all of Japan as we know it today. The north and eastern parts of Japan in particular were dominated by “barbarian” groups called Emishi whose origins are somewhat obscure but are probably ethnically different than early Japanese people.

To subdue these people, certain military commanders in the Imperial bureaucracy were granted a temporary title of sei-i taishōgun (征夷大将軍), or “Supreme Commander of Barbarian-suppressing Forces”. Since a military force needs a clear chain of command, someone had to be made the supreme commander, and this was what the Shogun was meant to do.

But everything changed after the Genpei War, and the fall of the Heike Clan.

After the Genji clan (a.k.a. the Minamoto) crushed the Heike clan, they assumed military control of Japan. The head of the Genji clan, Minamoto no Yoritomo, was granted the title of sei-i taishōgun by the Emperor permanently, and given the task pacifying the rest of Japan. The title became hereditary, not temporary, and thus created a new system of government in Japan.

The original Imperial Court, and its institutions, remained in place in Kyoto. However, practical control of Japan was managed through the new bakufu (幕府) government headquartered in the eastern city of Kamakura. This began a period of history called the Kamakura Period of 1185–1333.

From here, Japan’s history and its bakufu governments can be divided like so:

| Period | Capitol | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Kamakura Period (1185–1333) | Kamakura | After Minamoto no Yoritomo‘s death, plagued with infighting and power-plays by vassals. Minamoto line died with Sanetomo’s untimely death, further heirs drawn from obscure Hojo relatives. |

| Southern Court Insurrection (1336 – 1392) | Yoshino | Emperor Go-Daigo attempts to reassert authority of the Imperial line. Kamakura Bakufu dispatches Ashikaga Takauji to suppress rebellion, but is betrayed by Takauji. |

| Muromachi Period (1336 to 1573) | Kyoto | First 3 shoguns were strong rulers, but quality of rulership slowly declines, culminating in 8th shogun Yoshimasa, and the disastrous Onin War. High point of Kyoto culture, ironically. |

| Warring States Period (1467 – 1615) | Kyoto (barely) | After Onin War of 1467, Ashikaga Shoguns still nominally rule until 1573, but country descends into civil war. Almost no central authority. |

| Oda Nobunaga (1573 – 1582) | Kyoto | After driving out last of Ashikaga Shoguns, Oda Nobunaga reaches deal with reigning Emperor and conferred titles of authority. Almost unifies Japan. Later betrayed and murdered by a vassal. |

| Azuchi-Momoyama Period (1585 – 1598) | Kyoto | After unifying Japan after Oda Nobunaga’s demise, vassal Toyotomi Hideyoshi unifies, and then rules Japan as the Sesshō (摂政, “regent to Emperor”) then Kampaku (関白, “chief advisor”). Dies in 1598, and son is too young to rule. Country falls into civil war again. |

| Edo Period (1600 – 1867) | Edo (Tokyo) | Tokugawa Ieyasu, a former vassal of Oda Nobunaga, then unifies Japan for the final time, and moves capitol to a newly fortified town of Edo (modern Tokyo). Effective policies by Ieyasu and his early descendants avoids many problems of past Shogunates, and provides stable rule for 268 years until Meiji Restoration of 1868. Similar to Muromachi period, quality of rulership gradually declines, but effective policies help maintain stability far longer.2 The last shogun, Tokugawa Yoshinobu, relinquishes authority back to Emperor at Osaka Castle in 1867. |

During this entire period of history, the Imperial line, and its Court of noble families in Kyoto never ended. The Southern Court vs. Northern Court briefly split the Imperial family into two competing thrones, but once they reunified, everything continued on as normal. The Emperors reigned, but the military governments ruled.

Once the Meiji Restoration of 1868 came, this changed, and with a new constitution borrowed from the Prussian model, the Emperor’s assumed direct control again until the modern constitution in 1947 when the Emperor returned to a mostly ceremonial role that we see today.

The series of Shogun takes place at the very end of the Azuchi-Momoyama Period to the very beginning of the Edo Period, but as you can see, Japan’s military history was far longer, and its many ruling families each faced different challenges. For the peasants on the ground, who they paid taxes to may have changed, but life overall probably remained somewhat the same.

1 I read the original book by James Clavell back in the day, including his other books: King Rat, Taipan, and so on. Great story-telling, especially King Rat (based on his personal experiences), but older me kind of facepalms now at the bad stereotypes, linguistic mistakes, and so on.

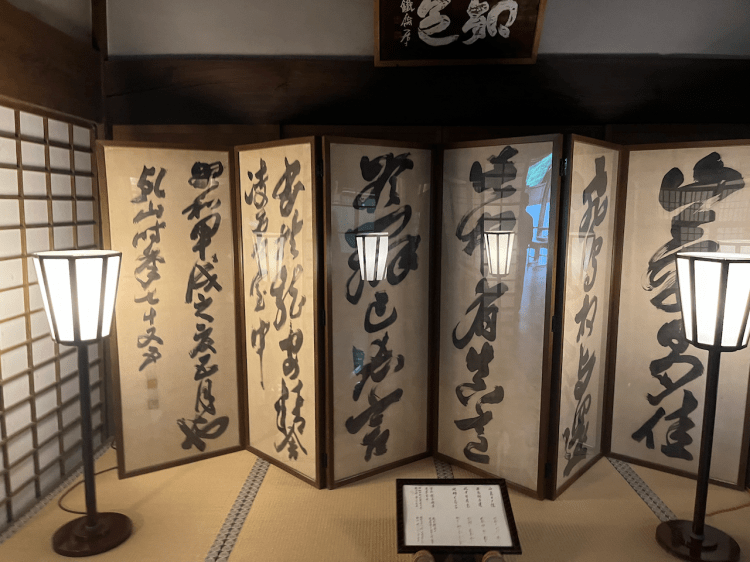

2 It’s also why, today, many historical dramas, comics and stories take place in the Edo Period. My father-in-law likes to watch one Japanese TV show called Abarenbo Shogun (暴れん坊将軍, “Unfettered Shogun”), which is a mostly fictional drama about the unusually talented 8th Shogun of the Edo Period, Tokugawa Yoshimune (1684 – 1751). In the drama Yoshimune, often traveling in disguise, solves mysteries and fights crime. It’s campy, but also a fun show to watch. The “Megumi” lantern shown on the right is a set piece from the show.

You must be logged in to post a comment.