I have been avidly playing the game Fire Emblem: Three Houses since fall of last year. Yes, the game is that good. But also the game makes you think about things too, including religion.

One of my favorite characters in the game, is the leader of the Golden Deer House, Claude von Riegan (also mentioned here and here), voiced in English by Joe Zieja. Claude’s background is unusual for the game’s cast, and he keeps his identity close to his vest, but needless to say he’s had a very worldly upbringing, and sees things different than the other students who mostly grew up in Fódlan. He is just as ambitious as Edelgard, but prefers to meet his goals in a more hands-off, less forceful way.1

Unlike most of his fellow students, who grew up within the Church of Seiros, Claude tends to be pretty cynical about Fódlan’s only religious organization, and regularly questions it (this is also important to certain elements of the plot, but that’s beside the point).

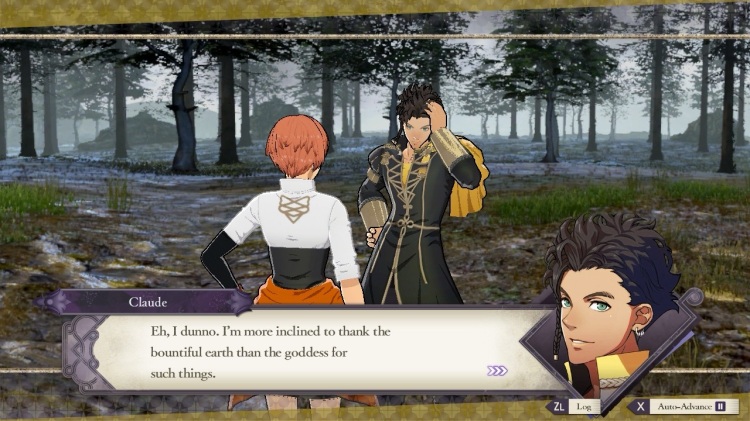

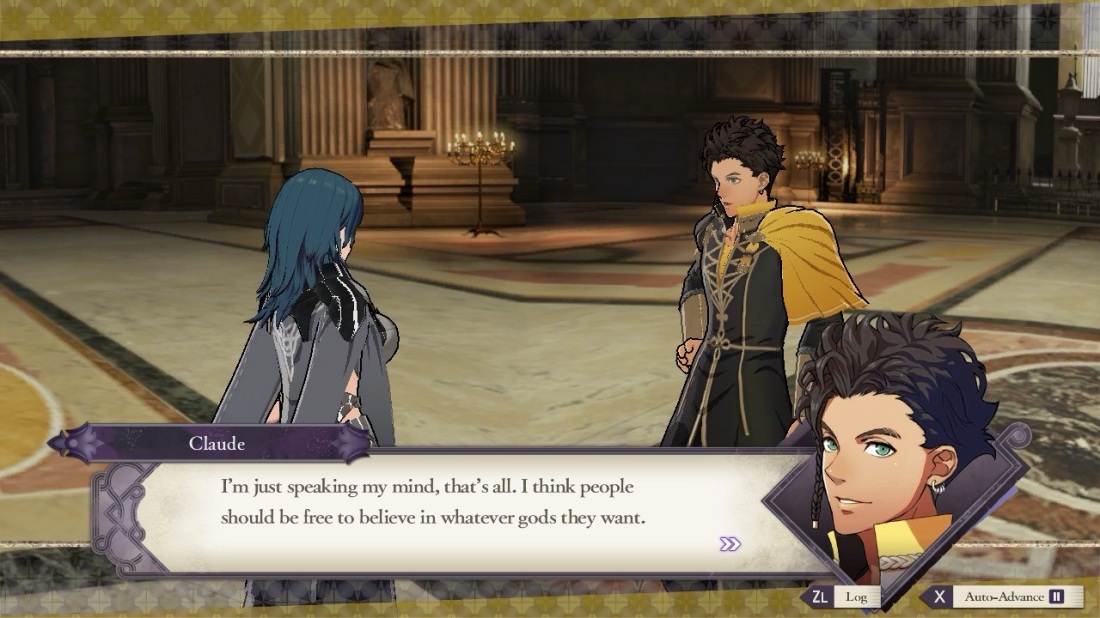

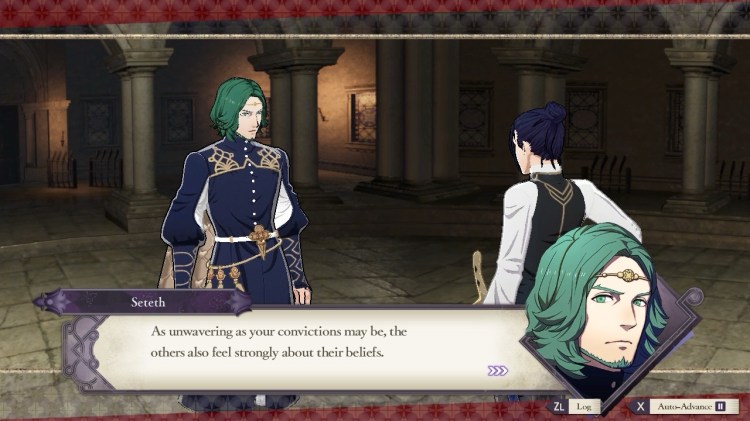

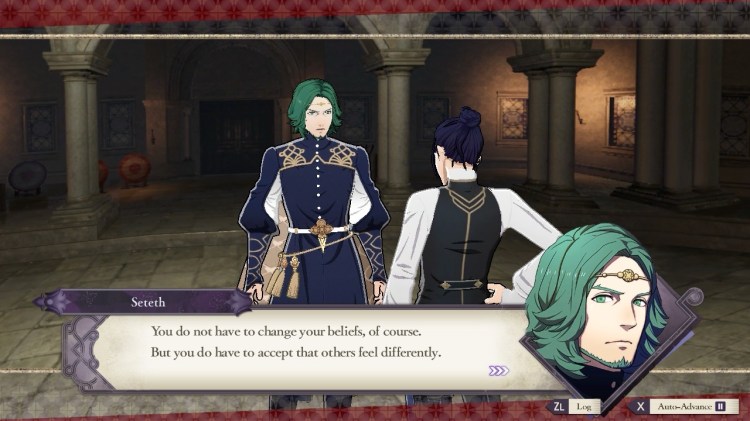

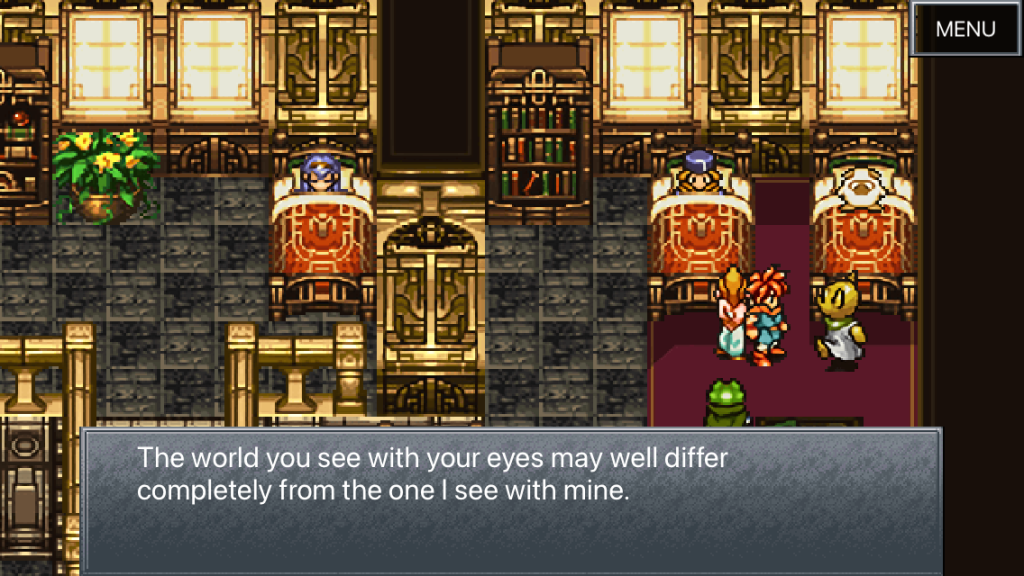

Anyhow, I wanted to share something he said that I think is worth considering (possibly out of order, I lost track of which is which):

Even though I tend to be an ardent Buddhist, I think what Claude is saying here is a healthy to look at the world and its religions. If you consider religions past and present, there have been countless gods and goddesses, rituals, liturgical languages, and so on. Even in in the same religions, practices and views diverge over time. This may offend purists, but it’s impossible to avoid, let alone manage.

Further, Buddhism has never been a particularly evangelical religion. It’s not in a race to win converts (minus a few cults), for a variety of reasons. First, this is in keeping with the Buddhist notion of metta (“goodwill”) that as long as other people have a belief system that helps them, not hinders or makes them feel bad, then that is fine. Second, the danger of imposing one’s beliefs on others is that it’s almost always fueled by ego and one’s own delusion anyway. A person’s religious beliefs, even Buddhist ones, are almost always a reflection of one’s own mind, and have to be taken with a grain of salt. Third, the Buddha clearly wanted people to take refuge in the Dharma of their own volition, and not by coercion. Even the Five Precepts are phrased as “I undertake” not as a command. Similarly with the practice of the nembutsu in Pure Land Buddhism. There’s nothing in the Buddhist canon that tells people to recite, or not recite it. It’s up to each individual to work with the tools offered in the Buddhist toolkit and apply them as best as they can. Like Claude says above, if you find a support system that works, great. This is no less true within Buddhism and its many traditions as well.

It’s generally better, and healthier for one’s own mental state, to let others be who they are, believe what they will, as long as its helpful, not harmful. The tighter one grasps, the more exhaustion and grief they inflict upon themselves, and others.

There are almost as many as variations on religious beliefs as there are people, so like the analogy of the Blind Men and the Elephant, each person is trying to feel their way through life using what resources, background and knowledge they have. Even within Buddhism, each person has their own “spin” on what the Buddha was, or what his teachings were.

It’s imperfect, but we all have to start from somewhere.

P.S. If you own a Switch, try Fire Emblem: Three Houses. 😋

1 Bit of a tangent, but of the three lords in Three Houses, I feel that Dmitri plays the role of the “conservative”, trying to restore his kingdom and the Church the way it was. Claude is the “liberal” trying to open things up and hoping it will change Fódlan, while Edelgard is the “revolutionary” who wants to change things directly (i.e. through force).

Then, while exploring the

Then, while exploring the

You must be logged in to post a comment.