Garibaldi: This isn’t gonna be easy.

Babylon 5, “And the Rock Cried Out, No Hiding Place”, s3:ep20

G’kar: Nothing worthwhile ever is.

Recently, I talked about the key to practicing Zen (or Buddhism in general) is training while incorporating other things in your life toward that same goal. Like Rocky Balboa training in Rocky, or Li Fong in the excellent movie Karate Kid: Legends, or someone working hard to learn a language by making other aspects of life conducive toward language learning.

In most cases, we go through a some stages when we take up a project like this.

- New thing – “this is fun, I can see the benefits already!”

- Steady practice – “gotta keep this up”

- Boredom – “ugh, I gotta do this again”

- Skipped days – “I’ll make up for it tomorrow”

- More skipped days – “No, really, I’ll make up it up tomorrow.”

- Guilt – “I suck”

- Despair – “I’ll never succeed.”

- Quitting.

My usual pattern with new projects, or dieting and exercise, is to eventually feel guilty, despair, and quit. It happens to me a lot over the years, admittedly.

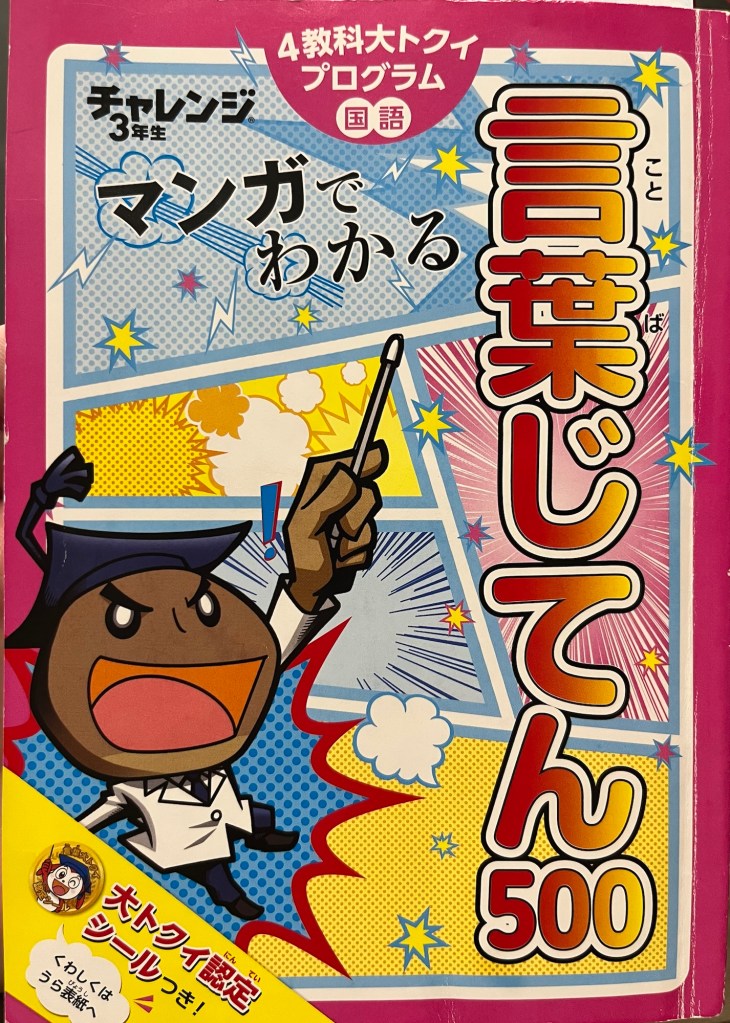

But also, there are a few things that surprisingly I have managed to stick with for years, decades even. I’ve been actively studying Japanese since 2008, for example. I realized though that the way I’ve studied Japanese has changed and shifted many times. Some experiments succeeded, others failed immediately. But the goal was important enough to me, that even when I failed I just shifted tactics and tried again. I failed the N1 JLPT twice in the last five years, and to my surprise, I am still at it, but now trying a new tactic.

Put another way: when I hit a roadblock, instead of hitting my head on the wall harder and harder, I tried another route. I knew where I wanted to go (language fluency) and just kept trying methods until I found something that stuck.

I realized too that my pursuit of the Buddhist path has been much the same way. I started out in 2005 with very little understanding, but I really liked reciting the nembutsu, and I loved the simple, down-to-earth, and highly approachable Jodo Shu sect as taught by Honen (still do!). But while I’ve had the same basic goal, my understanding of Buddhism has grown over time, and like language learning, has gone through many false-starts, projects that soon ended, or things that just didn’t work. So, I just shifted, tried another route, backtracked, and so on. This what I think happened to me, and why I took up Zen practice since May.

My current Zen practice is, I suppose, just another track toward my goal.

So, I think the point of all this is that the goal is more important than the particular approach. If the goal is something you really care about you’ll find a way. In fact, you’ll probably bend other aspects of your life toward it. If not, then the goal maybe wasn’t that important to begin with. That’s OK. Better to acknowledge it, cut your losses, and move on.

But if the goal is worthwhile to you, then like G’Kar says, you’ll find a way.

Namu Shakamuni Butsu

Namu Amida Butsu

You must be logged in to post a comment.