Hello,

Recently, I alluded to joining a local Soto Zen group and deepening my practice there. I am happy to report that after several weeks, I finally decided to formally join the community as a member. Thus, I guess I am now a student of Soto Zen.1 It is kind of exciting to be part of a Buddhist community again after years of isolation, but also a bit of an adjustment since I’ve been doing things a different way for a very, very long time.

As part of this I wanted to get familiar with the yearly liturgy of the Soto Zen tradition. To my surprise, the local community seemed to not follow this yearly calendar, but I guess it’s up to each follower, and each community to apply this calendar as much possible.2

Anyhow, I think it’s helpful to get familiar with the calendar of events not just to have a foundation in one’s life and practice, but also to stay connected with the much larger community. So, for that reason I’m posting the yearly event calendar here for readers. Many of these holidays line up with other Buddhist traditions in Japan, and I’ve already talked about them in other blog posts, while a few are exclusive to Soto Zen only.

| Date | Japanese | Event |

| January 3rd | 転読大般若 Tendoku Dai-hannya | Reading of the Great Perfection of Wisdom Sutra |

| February 15th | 涅槃会 Nehan-e | The Death of the Historical Buddha, Shakyamuni |

| Late March | 彼岸会 Higan-e | Spring Equinox |

| April 8th | 花まつり Hanamatsuri | The Birth of the Historical Buddha, Shakyamuni |

| Late July / Late August | 盂蘭盆会 Urabon-e | Obon Season |

| Late September | 彼岸会 Higan-e | Fall Equinox |

| September 29th | 両祖忌 Ryoso-ki | Memorial for both founders of Soto Zen: Dogen and Keizan |

| October 5th | 達磨忌 Daruma-ki | Memorial for Bodhidharma, the Indian monk who brought the Zen tradition to China. |

| December 8th | 成道会 Jodo-e | The Enlightenment of the Historical Buddha, Shakyamuni |

| December 31st | 除夜 Joya | End of the year temple bell ringing |

Let’s talk about some of these events below.

Reading of the Great Perfection of Wisdom Sutra

The Great Perfection of Wisdom Sutra requires some explanation. The Sutra is not one Buddhist text, but a collection of sutras that appeared in India starting in the 1st century CE. Each of these “great perfection of wisdom” sutras (a.k.a. prajña-paramita in Sanskrit) basically teaches the same message, but each version was composed in varying sizes: 8,000 verses, 15,000 verses, 25,000 verses, etc. The trend happens in reverse too: some versions get shorter and shorter until you get to the famous Diamond Sutra and Heart Sutra. Due to their slimmer size and easier recitation, these two sutras have retained more popularity over time.

Nevertheless, regardless of which version we’re talking about, the Great Perfection of Wisdom Sutra is a powerful foundation for Mahayana Buddhist traditions everywhere, including the Zen tradition. Thus, many traditions have some kind of “sutra reading” ceremony.

Because the Perfection of Wisdom Sutra is so large, it’s impractical to read/recite the entire sutra in a single session, so the ceremony usually involves Buddhist monks opening each fascicle and fanning through the pages to symbolize reading it. It’s a very formal ceremony. You can see an example of this below, though I am unclear which Buddhist sect this is:

English-language copies of the Great Perfection of Wisdom Sutra are very hard to find, by the way. I consider myself very lucky to find a copy of the 8,000-verse sutra at Powell’s City of Books some years back (that bookstore is amazing by the way):

Most Zen communities in the West can’t be expected to have such a copy. In any case, since the Heart Sutra is a summation of the Great Perfection of Wisdom Sutra anyway, it makes sense for most Zen practitioners to simply recite the Heart Sutra as appropriate. In the Youtube video above, the monks even recite the Heart Sutra at one point too.

Dual Founders Memorial

Soto Zen is somewhat unusual in Japan for having two founders, not one. The sect-founder-practice dynamic is something unique to Japanese Buddhism,3 usually each recognized Buddhist sect in Japan has one founder, not two.

Normally, when Westerners think of Soto Zen in Japan, they think of Dogen as the founder since he was the one who traveled to Song-Dynasty China, studied Caodong-sect Zen teachings, and brought those back to Japan.4 The challenge is that during this time, Soto Zen was a strictly monastic institution that had minimal appeal to the wider Japanese society.

Keizan, who came a few generations later, reformed Soto Zen as an institution that had more broad appeal. It was still centered around the monastic institution, but also included more community connections to the warrior samurai class and the peasantry as well. Soto Zen flourished in a way that other Zen sects in Japan simply never did. For this reason, Keizan is considered the second founder.

Thus, during formal ceremonies, a Soto Zen text, the ryōsokisho (両祖忌疏) is read aloud, which describes the virtuous life of both founders through the use of Chinese-style poetry.

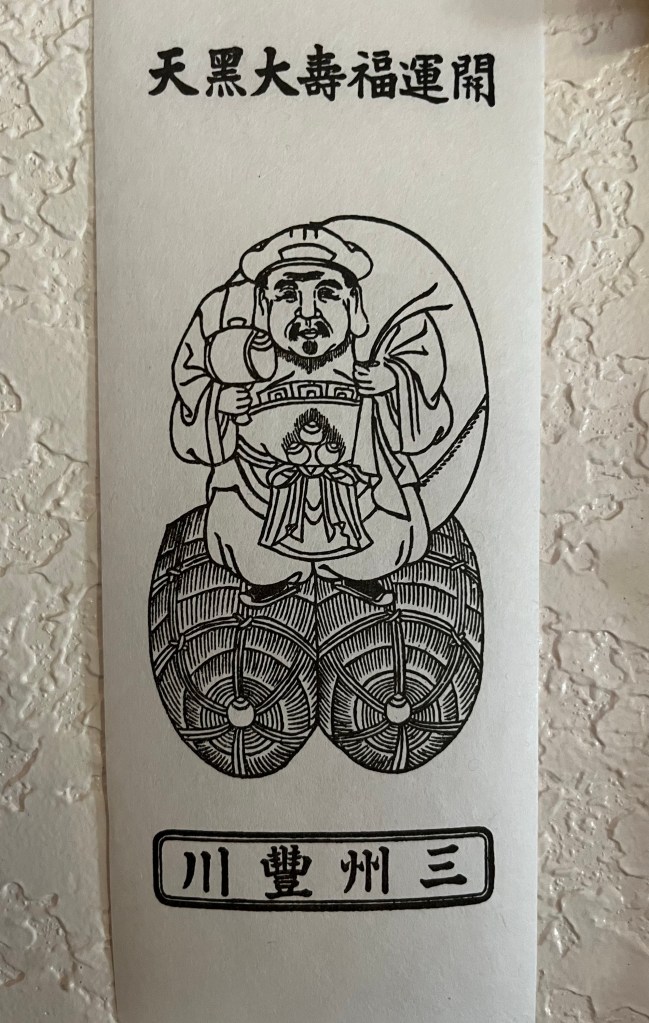

Bodhidharma Memorial

Within the world of Zen, Bodhidharma is a guy who needs no introduction. This semi-legendary monk from India supposedly came to China in the 4th century, and helped establish the lineage there, and subsequently all such lineages through East Asia.

The historicity of Bodhidharma though is pretty suspect, and some historians contend that he was made up in order to refute criticism that Zen had no prior connection to Buddhism in India. I don’t know which is true.

Regardless of whether Bodhidharma was real or not, he is the embodiment of Buddhism (particularly Zen) passing the torch from the community in India to the community in China and beyond.

End Of Year Temple Bell Ringing

The “joya” tradition is found across all Buddhist sects in Japan, and is a way of ringing in the new year. I took part in it once myself at a local Jodo Shu temple thanks to my father-in-laws connections.

The temple bell, or bonshō (梵鐘), is run 108 times, to signify the 108 forms of mental delusions (kleshas in Sanskrit, bonnō in Japanese) that all sentient beings carry with them. Things like anger, jealousy, covetousness, envy, ill-will, etc. In other words, the stupid petty shit we all do.

When I participated ages ago, this particular temple lined 108 volunteers up, and one by one we proceeded to the temple bell and rang it. As the temple bell is very large, and the striker is a large wooden log suspended by rope, this wasn’t easy, but it was cool.

Obviously, many communities in the West don’t have huge temple bells, and only tiny ones at home at their home altar. Still, one can relive the experience using a small bell, such as one found on your Buddhist altar, and ringing it 108 times (Buddhist rosaries can help keep count, by the way; that’s literally what they’re for), or some division of 108 if that’s not easy: 54, 27, etc.

Conclusion

The liturgical calendar of Soto Zen, as promulgated by the home temples in Japan, includes a lot of holidays that are practiced by the wider Mahayana Buddhist tradition anyway, plus a few novelties found only in Japan, or even just in Soto Zen itself.

Outside of Japan, how one incorporates this into one’s own community, or just in one’s personal life is entirely up to them. Personally, I like having some structure, including a set calendar like this to keep me from getting too idle, but also as a way to tie in to the larger Buddhist community as a whole. However, other people may differ.

Good luck and happy practicing!

Namu Amida Butsu

1 I should clarify that I haven’t stopped reciting the nembutsu and such, I just feel I moved onto the next phase of my Buddhist practice.

2 I have noticed over the years that communities here in the West are more or less connected to the home temple overseas. Some strive to stay in lock-step, some go the opposite route. I have mixed feelings on the subject.

3 TL;DR – The Edo Period government decided to divide-and-conquer previously militarized Buddhist establishments into distinct sects, where each one required to define their founder, their particular practice, and key sutras they base their teachings around. This led to the parochial style Buddhist institutions that still exist today, but also bucked the trend in continental East Asia where Buddhist sects tended to synthesize into a single “super-Buddhist” tradition.

4 Fun fact: the “Soto” is just the Japanese-style reading of Cao-dong: 曹洞. For a look at how Japan imported Chinese characters, and why they sound so different, you can watch this Youtube video. I have personal quibbles about some details, but it’s otherwise a great historical overview.

You must be logged in to post a comment.