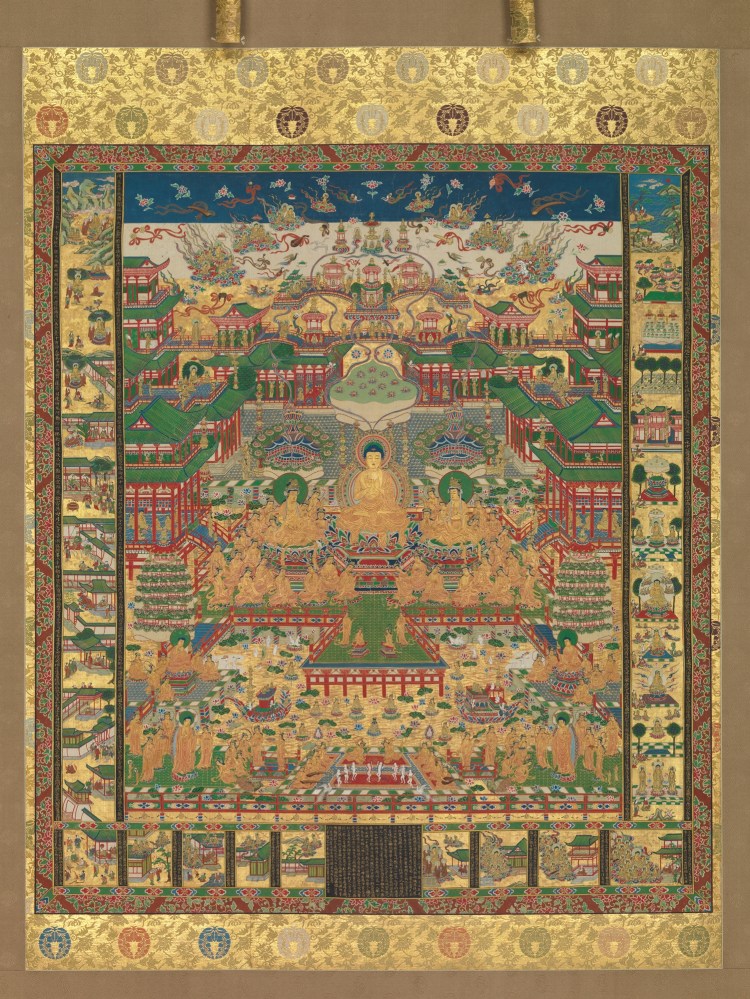

Author’s Note: this was another post I found recently from my old blog, possibly something I wrote in 2013 or 2014. It was shortly after this that I decided to leave the local Jodo Shinshu Buddhist community, give up the prospect of ordination, and strike out on my own. My feelings on the subject have changed somewhat, but I still agree with the general sentiment. I do miss many of my old friends at the local temple, but these days I am kind of done with Jodo Shinshu Buddhism. Apart from minor edits, and fixing broken links, this is posted as-is. Oh, and I added a cover image from that time and updated the title slightly for clarity. 😋

Lately, as I have been able to enjoy a small break in life, work and so on, I delved into some books I haven’t finished reading in a long while, including an excellent study on the life of Hossō Buddhist scholar, Jōkei. The book, titled Jokei and Buddhist Devotion in Early Medieval Japan by James L. Ford, is both a biography, but also a critical look at the late Heian, early Kamakura periods from a Buddhist perspective, and an effort to shed new light on this oft-studied and oft-misunderstood period.

In a way, I feel like I am betraying friends I have had the privilege of encountering over the years who are devout Jodo Shu and Shinshu Buddhists, but at the same time, I think Buddhism should be able to stand on its own two feet and take the acid test of criticism sometimes.1 To my friends on the Pure Land path, please forgive this post. It is not a personal attack, and I know many people in Jodo Shu and Jodo Shinshu who are admirable Buddhists in their own right. It’s just that while reading Ford’s book, I really felt he hit the nail on the head with certain things about Honen and Shinran’s teachings that made me uneasy, particularly the “exclusive” Pure Land approach that orthodox Jodo Shu and Jodo Shinshu followers adopt. Until recently though, I couldn’t quite articulate it myself.

This uneasiness came about back when I first started reading Rev. Tagawa’s book on Yogacara Buddhism, and on my recent trip to Kyoto and Nara, this old uneasiness arose in me moreso as I stood at the feet of great temples such in Kyoto and Nara. When I stood in the Treasure House of Kofukuji, beheld all the amazing artwork there, and the vast corpus of teachings they represented, I knew something was still amiss in my Buddhist path and it’s been gnawing on my mind for a while now.

Jōkei is best known as a sharp critic of Hōnen and the exclusive Pure Land movement, or senju nembutsu (専修念仏). As such, he was the primary author in 1205 of the Kōfukuji Sōjō (興福寺奏状), or the “Kofukuji Petition” to the Emperor which sought to suppress the “exclusive nembutsu” Pure Land school started by Honen. History has not been kind to Jokei, and Professor Ford argues that the study of Kamakura Buddhism is flawed because of some underlying biases and assumptions about “old” vs. “new” Buddhism. Meiji-era and later studies tend to apply a kind of “Buddhist revolution” to Honen and Shinran, and paint traditional Buddhist sects as elitist or oppressive. Sometimes, parallels between Shinran and Martin Luther have been drawn in scholarly circles, though more modern research has refuted this analogy as superficial at best.

A while back, after reading Dr. Richard Payne’s collection of essays on the subject of Kamakura-era Buddhism, I started to question these assumptions, but more so after reading Ford’s book. He explores the Petition toward the last-half of the book and Jokei’s relationship with Honen to show how history has normally written about the incident, and carefully dissects it to show another viewpoint. In essence, he argues that Jokei’s criticism of Honen isn’t an “old-guard” or “elitist” perspective, but more accurately reflects a “normative” Buddhist doctrinal stance.

Ford explores at length about the content of Jokei’s Kofukuji Petition and its nine articles faulting the new senju nembutsu (専修念仏) or “exclusive nembutsu” movement, which are Ford summarizes in four points (I am quoting verbatim here):

- [According to Jokei,] Honen abandoned all traditional Buddhist practices other than verbal recitation of the nembutsu.

- Honen rejected the importance of karmic causality and moral behavior in pursuit of birth in the Pure Land.

- Honen false appropriated and misinterpreted Shan-tao with respect to nembutsu practice.

- Honen’s teachings had negative social and political implications.

To bolster his stance in the Petition, Jokei uses the same textual sources as Honen to demonstrate that Honen only selectively drew certain teachings from Chinese Pure Land patriarchs, Shan-Tao, Tao-ch’o and T’an-luan to prove his beliefs concerning the verbal nembutsu, while ignoring the whole of their teachings and writings, which included a more comprehensive Pure Land Buddhist path. Ford then turns to modern scholars to show that in China, the nembutsu (nian-fo) was never seen as a verbal-only practice even in Shan-tao’s time, but was interpreted as a well-developed meditation system. This is reflected even in modern day Chinese Buddhist writings, such as those of the late Ven. Yin-Shun.

As Ford then concludes:

Thus Jōkei’s claim that the Pure Land schools had no precedence in China is probably true. All in all, Jōkei’s critique of Honen’s construction of an independent Pure Land sect based on exclusive practice of the oral nembutsu is generally well grounded both doctrinally and historically. (pg. 178)

Jokei’s accusation that Honen abandoned the karmic law of causality and undermined the Buddhist teachings for upholding moral conduct, also weighs heavily. Jokei asserts the traditional Buddhist view2 of time as infinite, and that people are responsible for their own karma and the pursuit of wisdom. From Jokei’s perspective, one’s poor conduct can forestall one’s rebirth in the Pure Land, or reduce the conditions of rebirth itself. He notes the Nine Grades of Rebirth in the Contemplation of Amitabha Sutra, but I am personally also reminded of the proviso in Amida Buddha’s 18th Vow in the Immeasurable Life Sutra:

Excluded, however, are those who commit the five gravest offences and abuse the right Dharma.

Or Shakyamuni’s admonition in the same Immeasurable Life Sutra:

Anyone who sincerely desires birth in the Land of Peace and Bliss is able to attain purity of wisdom and supremacy in virtue. You should not follow the urges of passions, break the precepts, or fall behind others in the practice of the Way. If you have doubts and are not clear about my teaching, ask me, the Buddha, about anything and I shall explain it to you.”

One’s poor conduct doesn’t prevent the Vow of Amitabha Buddha from being fulfilled, but delayed and hindered for a time, Jokei argues. Either way, Jokei reinforces a traditional Buddhist view of the importance of karmic causality as central to Buddhism, inline with the teachings of Shakyamuni Buddha himself in countless, countless, countless sutras. As evinced elsewhere in the book, Jokei like many Buddhists believes in the power of Amitabha and his Vows to bring people to the Pure Land, but also asserts that one is still responsible for their karma, so one has to meet Amitabha Buddha half-way in a sense. Jokei’s many sermons and devotions to Kannon, Maitreya and others show that he often advocated this “middle” approach between devotion and personal practice/responsibility and Ford argues that this was the normative approach to Buddhism taken through out Asian Buddhist history.

Indeed, in Jokei’s words describing himself:

[My opinion] is not like the doubt of scholars concerning nature and marks, nor is it like the single-minded faith of people in the world. (pg. 179)

Meanwhile, later Ford shows how Jokei by contrast:

…represents a ‘middle-way’ between the extremes of ‘self-power’ and ‘other-power.’ He was not unique in this respect, since this perspective, though perhaps unarticulated, predominated within traditional Buddhism — despite the rhetorical efforts of figures like Honen and Shinran to paint the established schools as jiriki (self-power) extremists. (pg. 202)”.

But nevertheless, Ford shows how modern scholars in Japan and in the West have skewed this view of history with the belief that the politics of medieval Japan were reactionary, and stifling Buddhism in Japan at the time, leading to the Pure Land movement. Here, I quote Ford directly (emphasis added):

Hōnen’s response to the apparent social inequity and underlying monastic/lay tension — always a feature of Buddhism — was, in effect, to abolish the traditional lay-monastic framework. I am not convinced that he meant to destroy the system, particularly given his devotion to the monastic life, but the effect of his message, as revealed in the Senchakushū, was to undermine the practices and doctrines that sustained the monastic ideal. Pronouncing them obsolete because of the limitations of the age, he concluded that salvation was no longer contingent upon precept adherence, meditative practice, or diligent effort toward realization. Realization was now deemed a secondary goal, since it could not be attained in this world; it could only be attained in Amida’s Pure Land. Although others before Hōnen had devised “simple” practices to address the needs of lay practitioners and lessen the tension noted above, an implicit contradiction remained. If these practices could deliver as promised, why go through the arduous training of a monk? The monastic ideal could be interpreted as an ever-present source of doubt with respect to the efficacy of the “simple” practices. Hōnen can be seen, at least in terms of effect, as one who address this doubt directly, but Shinran appears much more explicitly conscious of this issue. (pg. 183)

Ford then adds:

We certainly cannot fault Hōnen and Shinran for creatively adapting these well-established labels [self-power/other-power, “easy” and “difficult” practices] for their own proselytizing ends. However, we must dismiss these sectarian rhetorical categories as legitimate analytical categories in the study of Kamakura Buddhism. (pg. 202)

Summing up here, I think Ford gets at two critical points here. First, in mainland Asia, historically Pure Land teachings have never been divided along exclusive or sectarian lines, and such was even the case for early medieval Japanese Buddhism:

Scholars generally agree that the tradition of the Pure Land in China represented more of a “scriptural tradition” than a “doctrinal school” and that people of many different schools practiced the nien-fo [nembutsu]. Thus, Jōkei’s claim that the Pure Land schools had no precedence in China is probably true.

A sectarian, exclusive Pure Land Buddhism quite literally did not arise until Honen and later Shinran’s time. Ford is right in crediting them with adapting teaching to suit a need, and I write this with a heavy heart because I actually like both Honen and Shinran, but I agree that the effect, perhaps unintended, was to foster a kind of narrow sectarianism that didn’t exist in Pure Land Buddhist teachings and practices before. I guess it was the sign of the times.

And yet in the modern world, there are many Buddhists in Asia, Japan and the mainland, who are devoted to Amitabha Buddha and still follow traditional Buddhist practices in some form or another. Such people have not forgotten the important balance of sila (moral conduct), samadhi (practice) and paññā (wisdom) even as they strive for rebirth in the Pure Land. Indeed the late Ven. Yin-Shun in his book The Way to Buddhahood, taught a comprehensive approach not unlike that which Shan-tao and Tao-ch’o offered many centuries ago:

The chanting of “Amitabha Buddha” should also be accompanied by prostrations, praise, repententance, the making of sincere requests, rejoicing, and the transference of merit. According to the five sequences in the “Jing tu lun” (Pure Land Treatise),3 one should start with prostrations and praise and then move into practicing cessation [meditation], contemplation [more meditation], and skillful means. One can thereby quickly reach the stage of not retreating from the supreme bodhi. As Nāgārjuna’s Śāstra puts it “those aiming for the stage of avivartin [non-retrogression] should not just be mindful, chant names and prostrate.

It’s a well-established trend, and works for many people in the world, but only in Japan is there a separate trend toward exclusivity and the idea of traditional Buddhism being invalidated. The sense of Dharma Decline so critical to Japanese Pure Land in today’s climate seems like a subjective anachronism now, and difficult to base a doctrine on with so great a diversity of sanghas and teachings in the world.

Second, what I believe to be the stronger refutation of Japanese Pure Land Buddhism as traditionally practiced in Jodo Shinshu and Jodo Shu is summed up in the following passage which deals with the issue of hōben (方便) or “expedient means” (again, emphasis added):

Both in his religious practice and, specifically, the Sōjō, Jōkei’s articulation of the normative voice of inclusivism and diversity within Buddhism is again instructive. The content of this vision of Buddhism, grounded in the tradition’s emphasis on karmic causality, appears almost boundless at times. Hōnen’s exclusive claims of efficacy, resonating with much of the contemporary Tendai hongaku discourse and effectively undermining the moral implications of karma and its ramifications for Buddhist soteriolology, was a wholesale rejection of Buddhist tradition. It invalidated not only the devotion to the variety of Buddhas and Bodhisattvas that manifest different qualities of wisdom and compassion but also the importance of various kinds of ascetic practices, long the centerpiece of monastic life. In short, Hōnen’s teaching “delocated” Buddhist sacrality from its traditional broad manifestations — temporal and spatial — to one single exclusive manifestation. (pg. 203)

Again, I think back to my experiences in Nara, Japan in particular. At Todaiji alone, I saw six or seven temples on the temple grounds devoted to various figures of Buddhism. The plurality was amazing, and welcoming in a way. It felt inclusive, not exclusive, and there was no sense of guilt in praying to Jizo Bodhisattva, or the Lotus Sutra, one might feel in a Jodo Shinshu temple for example4 While there, if all I wanted to do was see Kannon, I could do so, but if I wanted to see other figures too, no problem. In other words, the broad, inclusive nature of Nara-style Buddhism allows Buddhists to offer as much or as little devotion to their heart’s content. No need to worry about doctrinal clashes or implicit guilt.

Thus, my faith in Amitabha Buddha and the Pure Land is no less than it once was, but Ford’s and Jokei’s writings and my experiences in Nara and Kyoto remind me that Buddhism is strongest in diversity, and later Kamakura schools of Buddhism have a tendency toward exclusivity. Japanese Pure Land Buddhists, along with some Zen and Nichiren Buddhists, argue that exclusive approach is simpler and more accessible, but given what other Buddhists faiths I’ve seen, I believe the exclusive approach is ironically less simple and less accessible by virtue of their exclusivity. Too much rationalization, cutting off, and justification while the rest of the Buddhist world quietly hums along to a relatively consistent tune, even with all its own faults.

The inclusive approach exemplified by Jokei, and Ford’s argument that it’s the normative Buddhist approach for most of the Buddhist world, allows considerable flexibility to follow an approach that works for you, without having to deny other paths as too difficult, elitist or only valid during a “better era” of Buddhism. Just follow which aspect you tend to have a karmic connection toward, whether it be Amitabha Buddha, Shakyamuni Buddha, Kannon, zazen, tantra, or some combination.

First and foremost, I guess I consider myself a Mahayana Buddhist and second a Pure Land follower, not the other way around. So, what does this mean for me? I think I already know the answer, but I’m holding off for now to think further. Jokei’s “middle of the road” approach to Buddhist devotion and practice, and inclusiveness, provides a lot of inspiration right now, along with my experiences in Japan, and I hope to explore this more as time goes on.

Namo Shaka Nyorai

Namo Amida Butsu

P.S. More regarding the critical role karmic causality plays in Buddhism from Ven. Thanissaro Bhikkhu

P.P.S. More on the subject of inclusiveness/exclusiveness in Pure Land Buddhism.

1 This would normally be the time to bring up the classic Kalama Sutta text, an awesome, though often quoted out of context in Buddhist writings. Instead, I’ll encourage you to read it yourself in full. It really is one of the best sutras in Buddhism. 🙂

2 Exemplified in the Yogacara/Hossō school in particular amongst the Nara Buddhist schools, and in opposition to Tendai “hongaku” or “innate enlightenment” teachings, and Shingon teachings regarding the “womb of Buddhahood”. It was one of the most tense and long-standing doctrinal feuds in Japanese Buddhism all the way until after Jokei’s time when some reconciliation was made. Ford does not elaborate on how this was done.

3 To be precise the Pure Land Treatise is: 淨土論, Ching-t’u-lun (Wade-Giles) or Jìngtǔ lùn (Pinyin), composed by Jiacai (迦才, ca.620-680).

4 Some Shinshu Buddhists I’ve met have explained it’s OK, as long as it’s an expression of gratitude but again there’s that subtle “if” in there.

You must be logged in to post a comment.