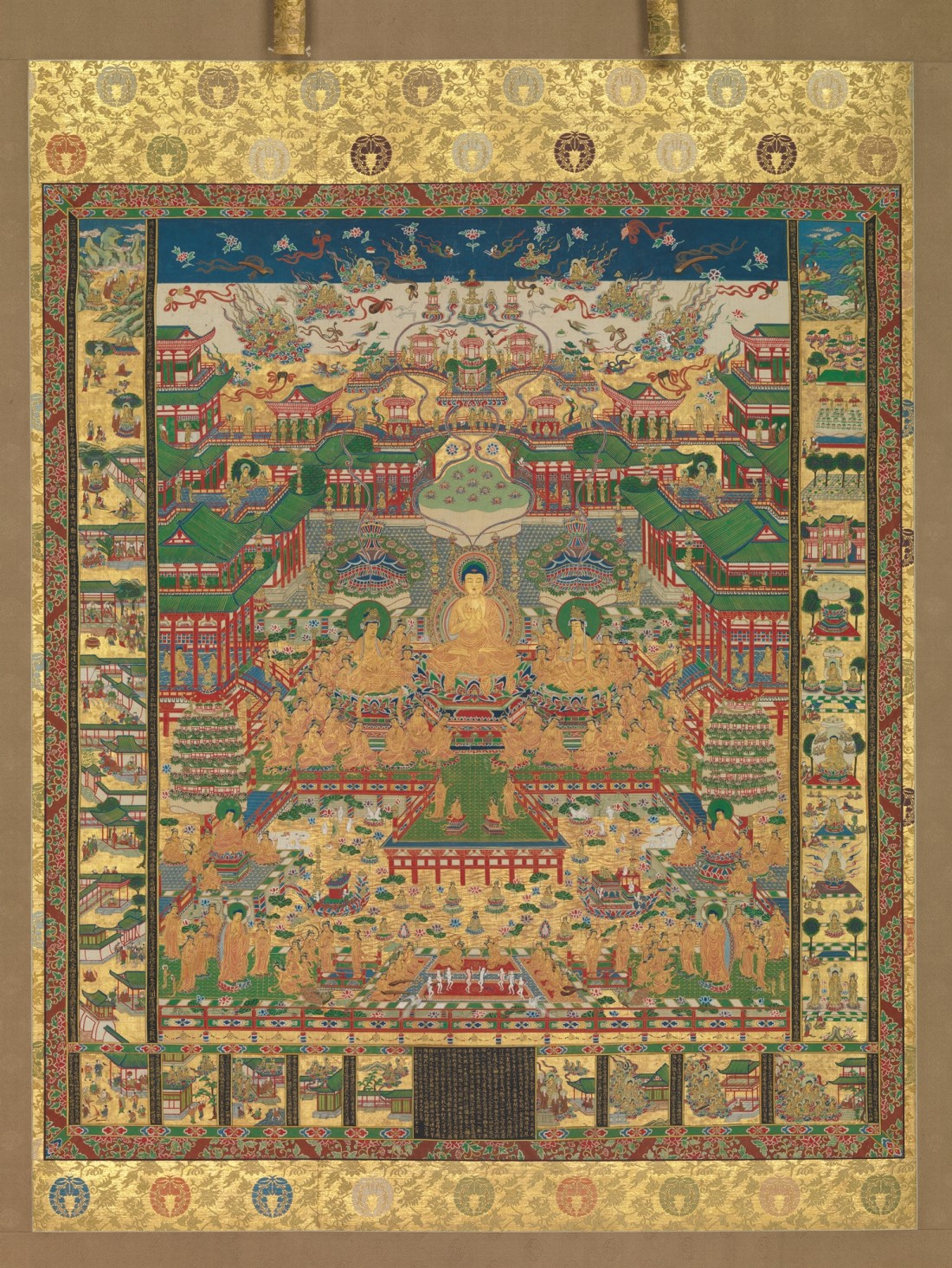

The nianfo (念佛) is widely recited across many cultures and languages by people who follow the Pure Land Buddhist tradition. In Japanese it is called the nembutsu (念仏), and that is the name I most often use on this blog. In Korean it is the yeombul (염불), and in Vietnamese it is the niệm phật. Just as the name differs by language, the phrase itself has changed pronunciation as it is adopted in other cultures and languages, just like the sutras did.

Let’s look at examples.

The original form of the nianfo (as far as I can tell) comes from Sanskrit language in India. In Sanskrit, “nianfo” was buddhānusmṛti (buddhānussati in Pāli language). The venerable site Visible Mantra states that it was recited like so:1

namo’mitābhāyabuddhāya

In the Siddham script, still used in some esoteric practices, this is written as:

𑖡𑖦𑖺𑖦𑖰𑖝𑖯𑖥𑖯𑖧𑖤𑖲𑖟𑖿𑖠𑖯𑖧

From here, Buddhism was gradually imported into China from India (a fascinating story in and of itself), and because Chinese language and Sanskrit are so different, this was no easy task. Nevertheless, the buddhānusmṛti was translated as nianfo (念佛) and written as:

南無阿彌陀佛

This was how the Chinese at the time approximated the sound of the Sanskrit phrase. In modern, Simplified Chinese characters this looks like:

南无阿弥陀佛

But how does one read these characteres? That’s a fun question to answer.

You see, Chinese has many dialects because of geography, regional differences, and migration of people. Thus, even though Chinese characters are written the same (with only modest regional differences), the way they are read and pronounced varies. Thanks to Wiktionary, I found a helpful list to illustrate:

| Dialect or writing system | Pronunciation |

|---|---|

| Mandarin, Pinyin system | Nāmó Ēmítuófó or Námó Ēmítuófó |

| Mandarin, Zhuyin (Bopomofo) system | ㄋㄚ ㄇㄛˊ ㄜ ㄇㄧˊ ㄊㄨㄛˊ ㄈㄛˊ, or ㄋㄚˊ ㄇㄛˊ ㄜ ㄇㄧˊ ㄊㄨㄛˊ ㄈㄛˊ |

| Cantonese, Jyutping system | naam4 mo4 o1 mei4 to4 fat6 naam4 mo4 o1 nei4-1 to4 fat6 naa1 mo4 o1 mei4 to4 fat6, or naa1 mo4 o1 nei4-1 to4 fat6 |

| Hakka, Sixian or Phak-fa-su system | Nà-mò Ô-mì-thò-fu̍t Nà-mò Ô-nî-thò-fu̍t Nà-mò Â-mì-thò-fu̍t |

| Eastern Min, BUC system | Nàng-mò̤-ŏ̤-mì-tò̤-hŭk |

| Puxian Min, Pouseng Ping’ing system | na2 mo2 or1 bi2 tor2 hoh7, or na2 mo2 or1 bi2 tor2 huoh7 |

| Southern Min (a.k.a. Hokkien), Peh-oe-ji system | Lâm-bû O-bí-tô-hu̍t Lâm-bû-oo-mì-tôo-hu̍t |

Of these dialects, I am only familiar with Mandarin and (to a much lesser extent) Hokkien, so I can only trust the others based on Wikipedia.

Anyhow, China was a powerful, dynamic culture at the time, and it had a profound influence on its smaller neighbors such as the Korean peninsula, Japan, and northern Vietnam (a.k.a. Dai Viet). Just as the neighbors of the Romans (including the Byzantines) absorbed Roman culture, the neighbors of China did the same even though the languages were very different.

Thus, the nembutsu in these languages became:

| Language | How to Recite |

|---|---|

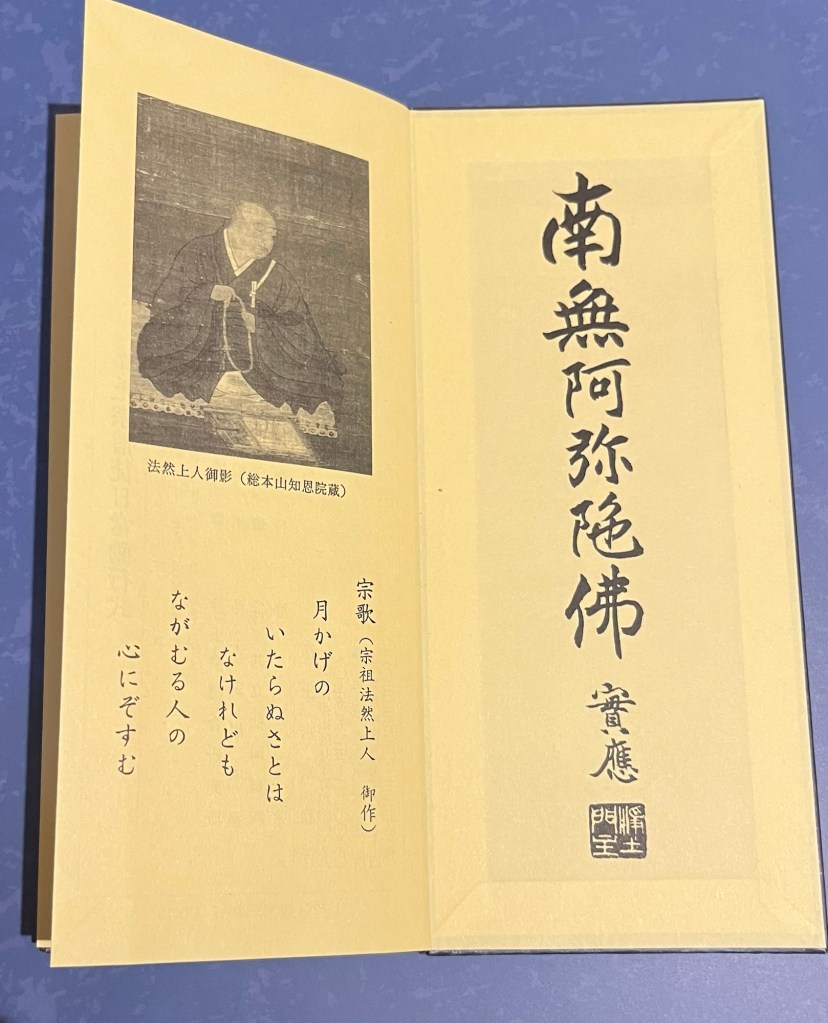

| Japanese | Kanji: 南無阿弥陀仏 Romaji: Namu Amida Butsu |

| Korean | Hanja: 南無阿彌陀佛 Hangul: 나무아미타불 Romanization: Namu Amita Bul |

| Vietnamese | Chữ Hán: 南無阿彌陀佛 Quốc ngữ: Nam mô A-di-đà Phật2 |

What about Tibetan Buddhism? I am really unfamiliar with that tradition, so I might be wrong here, but my understanding is that Tibetan veneration of Amida Buddha stems from a different tradition, so instead of the nianfo, they recite appropriate mantras instead. Beyond that, I don’t know.

Anyhow, this is a brief look at how a simple Sanskrit phrase has evolved into so many traditions and ways to express veneration to the Buddha of Infinite Light. Thanks for reading!

𑖡𑖦𑖺𑖦𑖰𑖝𑖯𑖥𑖯𑖧𑖤𑖲𑖟𑖿𑖠𑖯𑖧

南無阿彌陀佛

Namu Amida Butsu

P.S. Another post despite my intended rest. The time off really has helped, so it’s been well worth it, but now I am eager to write again. 😌

1 As I’ve written before, writing Sanskrit in the more modern Devanagari script is kind of pointless since Sanskrit was never written in that until late in history, long after Buddhism in India was gone. Sanskrit does not have a native script either, so the Roman Alphabet is as god as any.

2 Brushing off my college Vietnamese, this is pronounced as “Nam-moe Ah-zee-dah-fut”.

You must be logged in to post a comment.