After a couple recent posts, I realized that I had never covered a very weird, disastrous war in Japanese history: the Ōnin War (応仁の乱, Ōnin no Ran) from 1467 to 1477.

The Onin War is something most Westerners would not be familiar with, but it had a devastating impact to Japan that can still be felt today in Kyoto. The war spanned 10 years, but was almost entirely fought within and around the old capitol of Kyoto, rather than across the countryside. The war practically flattened Kyoto, and with it centuries of culture and history.

The war began as a succession dispute. After the current shogun of Japan, Ashikaga Yoshimasa (also arguably the worst shogun in Japanese history) adopted this younger brother to be his heir. Yoshimasa had no male heirs, and so this was a common practice. Unfortunately, his wife then gave birth to a son, which put Yoshimasa in a very awkward spot.

Two of the most powerful samurai families supporting Yoshimasa were divided about which person to support: Yoshimasa’s younger brother, or his infant son. The Hosokawa and Yamana clans were already feuding with one another, so this just gave them another axe to grind. The two main generals under Yoshimasa were:

- Hosokawa Katsumoto (細川勝元) – He supported Yoshimasa’s younger brother’s claim to be the heir.

- Yamana Sōzen (山名宗全) – He supported Yoshimasa’s infant son, intentionally to further oppose the Hosokawa.

Eventually, both sides secretly built up armies within the city of Kyoto to attack the other. Neither side had a clear advantage, and neither side could score a decisive victory. The Hosokawa had the support of the Shogunate, but the Yamana clan had 6 out of 7 gates to the city. Each side had 100,000+ soldiers in the city. Confusingly, the two opposing sides later switched the heir they supported, and as the war became increasingly pointless, the two sides fought simply because they didn’t want to lose to their rival.

As the war dragged on, both armies pulled in more allies and reinforcements from the provinces, fighting over and over again in the neighborhoods of Kyoto, destroying homes, temples, etc. Battles were fought street-by-street, neighborhood by neighborhood. They even fought at Buddhist temples just to gain some advantage over their opponent.

But after 10 years, both sides were exhausted, weakened and finally withdrew.

Old Kyoto was completely destroyed. When people in Kyoto talk about “the war” destroying Kyoto, they are not referring to World War II, but the Onin War. So much was lost in the destruction that Kyoto has never been quite the same. Many of the famous temples you see in Kyoto today were burned down during the Onin War (possibly other times too, buildings in Japan frequently suffer from fire).

According to Professor Donald Keene, the famous Zen master Ikkyū Sōjun described the destruction in a poem titled “On the Warfare of the Bunmei Era”:1

One burst of flame and the capital—gilt palaces and how many mansions— Turns before one’s eyes into a wasteland. The ruins, more desolate by the day, are autumnal. Spring breezes, peach and plum blossoms, soon become dark.

Part of the reason for such destruction was that old Kyoto was a city made almost entirely out of wood. Further, houses were very close to one another. Even the Yamana and Hosokawa compounds were within walking distance from one another. Also, as I’ve alluded to before, the countless dead and displaced were horrendous to behold, especially compared to the aristocracy of Kyoto that mostly made it out unscathed.

But where was the Shogun in all this?

Ashikaga Yoshimasa was, by hereditary right, the Shogun (将軍): the supreme military commander of Japan, and had authority over both the Hosokawa and Yamana clans. And yet, even after his poor decision making caused the war to begin with, when the conflict erupted, Yoshimasa shrugged and basically did nothing.

Yoshimasa had no force of personality to compel both sides to stop fighting, and although he came from long line of warriors, he was much more inclined toward the arts. Through the entire conflict, Yoshimasa did not take sides, nor lead troops into combat, though some of his relatives briefly did. Yoshimasa simply withdrew and, like an aristocrat, remained aloof to the conflict. Yoshimasa held lavish drinking parties and poetry contests even while fighting raged in the city and Kyoto was burning.

As a Shogun, Yoshimasa was absolutely the wrong man for the job, and yet, when he retired as a Shogun, he devoted all his time, money and efforts to culture and arts, and this helped start a new culture in Kyoto: the Higashiyama culture. The Higashiyama Culture was short-lived, and war resumed in Japan soon after, but many of the traditional arts that exist in Japan today were from this small period of time, promoted and elevated by Yoshimasa.

One can easily argue that few, if any, wars have any real value, but the Onin War is a spectacular example of a war that accomplished almost nothing, could have been prevented by competent leadership, and came at tremendous cost. Even stranger, the result of this tremendous death and destruction was a new flourishing culture that is at the heart of Japan today.

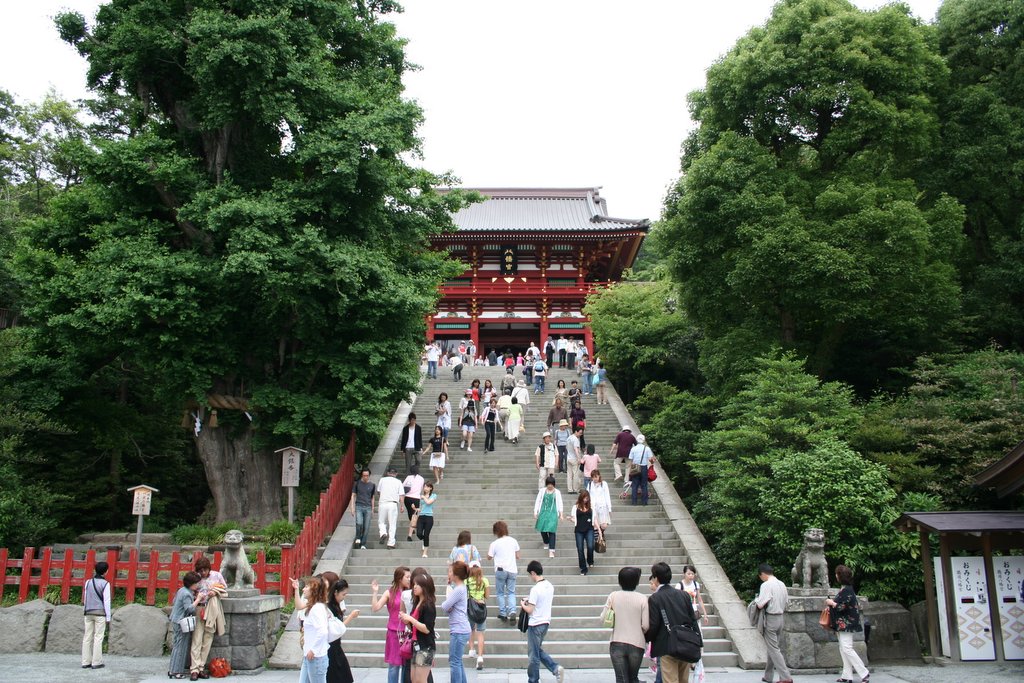

P.S. Featured photo is the Silver Pavilion of Ashikaga Yoshimasa, taken in 2010.

1 I tried finding this in Japanese, but I couldn’t. It was translated from a 1966 book called 五山文学集/江戸漢詩集 apparently.

You must be logged in to post a comment.