Visiting the city of Tokyo is not complete without taking a stop at the iconic Tokyo Tower. But what a lot of visitors might not know is that right next to Tokyo Tower is a Buddhist temple of great historical and cultural value: Zojoji

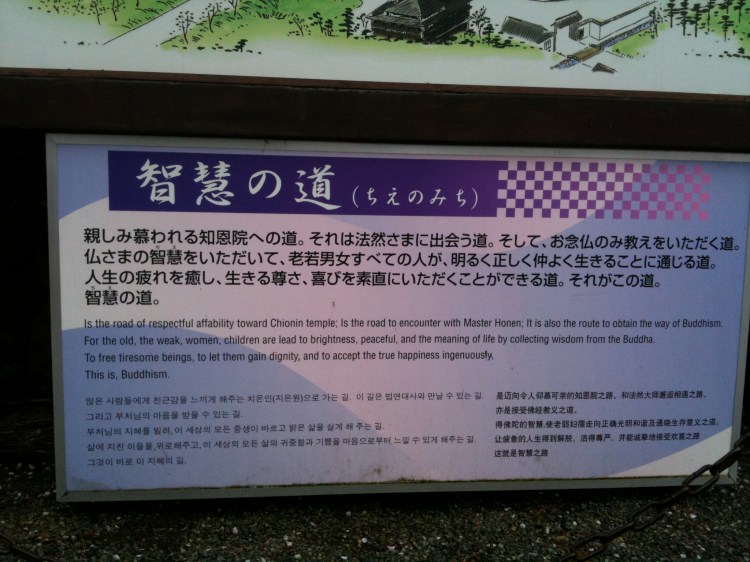

The temple of Zōjō-ji (増上寺) was the family temple for the Tokugawa shoguns who ruled Japan from 1600 to 1868 (e.g. the Edo Period), and many of the shoguns are interred here. The temple is also one of two main temples of the Jodo-shu sect of Buddhism. Jodo-shu Buddhism really helped me find my foundation back in the day, so I am more than a little fond of it. I have also visited the other main temple, Chion-in, in Kyoto a couple times. My first visit in 2005 is what really started me on the path to Buddhism back in the day. So, it’s no exaggeration that without the Honen the founder and Jodo Shu sect, I wouldn’t have found my path. I am always grateful.

In any case, wife (who’s Japanese) and I both like to come to Zojoji whenever we can. We joke it’s our “power spot”.1

The prestige and political power of Zojoji meant that it has been a very important temple in the Tokyo area for centuries, probably more so than Sensoji / Asakusa Temple (which I am also quite fond of).

The English website for Zojoji is actually pretty good, but it leaves out some details found in the Japanese version. Every time I go, I see foreign tourists dropping by, but I suspect some of them are unaware of the history and teachings of the temple, which is a shame because it’s actually a pretty neat place. So, this post is a lengthy tour of Zojoji. If you are reading this through email, you may want to visit the link instead. This post is VERY picture-heavy.

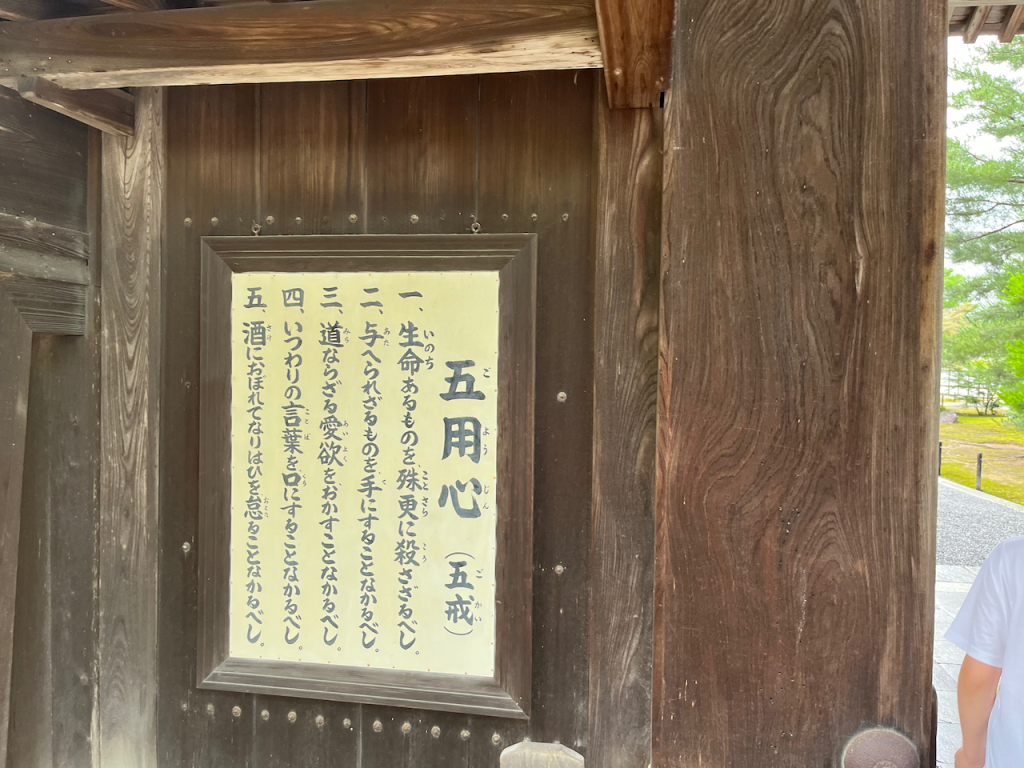

The Japanese site has a nice map of temple. I started at the bottom-center, at the Sangédatsu-mon (三解脱門), which might translate into something like the Three Gates of Liberation:

To the left of the gate is a sign that posts a monthly Buddhist teaching.

This month’s (August 2024) teaching is a quote from the very early Buddhist text, the Dhammapada, verse 54:

Not the sweet smell of flowers, not even the fragrance of sandal, tagara, or jasmine blows against the wind. But the fragrance of the virtuous blows against the wind. Truly the virtuous man pervades all directions with the fragrance of his virtue.

https://www.accesstoinsight.org/tipitaka/kn/dhp/dhp.04.budd.html

From here, I passed through the gate and took a photo of this statue of the Bodhisattva Kannon:

Next, based on the map linked above, I went clockwise around the perimeter of the temple. The next thing I saw was this pagoda (gojū-no-tō 五重塔 in Japanese) which seems to have been built in 1938:

It sits next to the other gate to Zojoji, the Kuro-mon (黒門, “black gate”) which was built in the 1700’s.

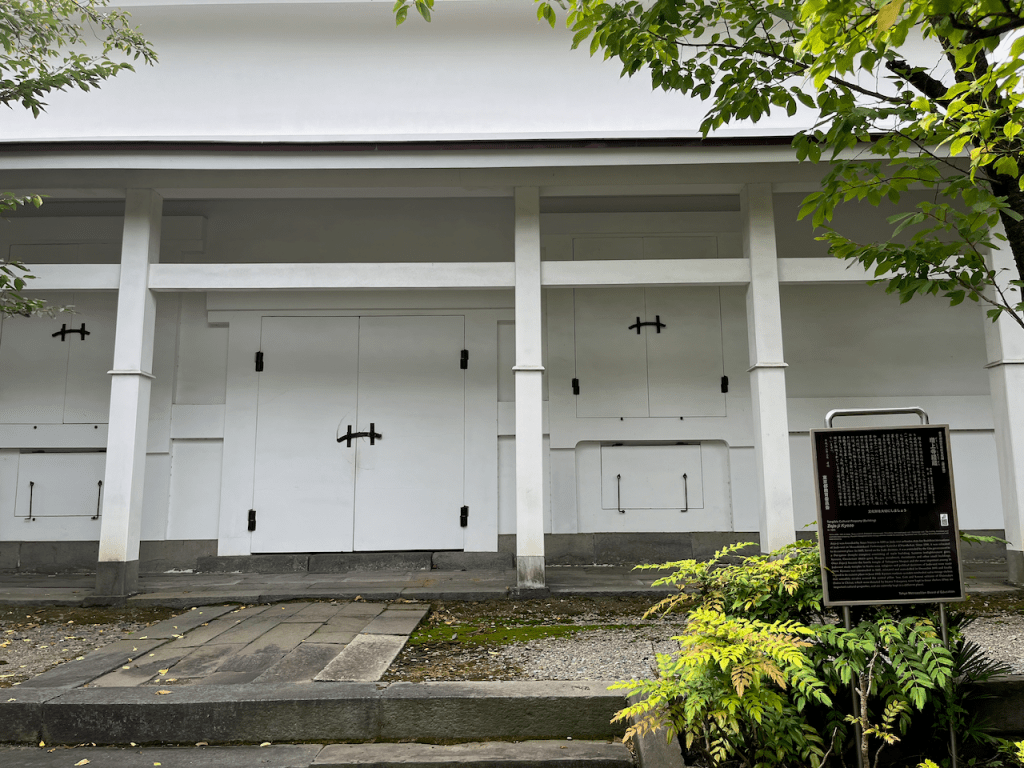

Just north of this (still going clockwise), you can see the Sutra Storehouse (kyōzō 経蔵):

This is something major temples often have: a large store house that contains the vast corpus of Buddhist literature (sutras): the Tripitaka. Sadly, I came too early in the day, and so the doors were closed. If you click on the map above, and look in the bottom left for 経蔵 you can see photo of the interior. It contains a full copy of the Taisho Tripitaka, in three different versions, in a rotating shelf.

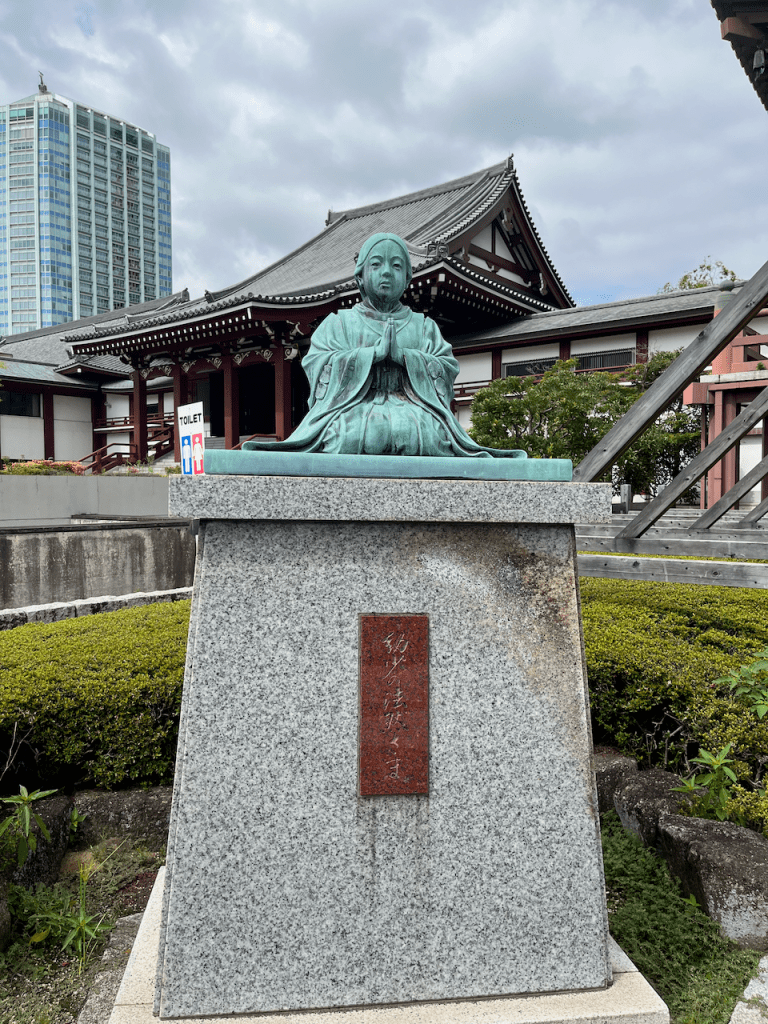

The left area of the map mostly contained meeting halls and offices, so I kind of skipped past this quickly, and headed toward the main hall (hondō 本堂). This is in the very center of the map. Just to the left of the stairs is a nice statue of the 12th century founder of the Jodo-shu sect, Honen, in his youth:

There are some famous stories about his life (somewhat embellished, I believe), including his piousness at a young age. Hence, you often see Jodo-shu temples with status of young Honen. That said, Honen is a cool guy, and he gets my respect any day.

Next is the main hall itself:

This place is pretty amazing inside. Also, unlike many temples, you do not need to remove your shoes at the door and you are welcome to take photos (except during funeral services, obviously):

The main altar is to Amida Buddha, the Buddha of Infinite Light, and the devotion of all Pure Land Buddhists across traditions. The gold color and lotus artwork are all taken from descriptions of the Pure Land, as described in the Sutras. It is said all beings reborn in the Pure Land will have the color of gold, just like Amida, and will be born from lotus buds. The Taima Mandala, not related to Zojoji, provides a nice visual representation.

To the left and right of the main altar are Honen, mentioned above, and Shan-dao the Chinese Pure Land master who inspired Honen back in the day, respectively. They lived centuries apart, but both are revered for their contributions to the tradition.

To the right of the main hall you have two choices: one you go down the stairs to the Museum. Or go to the Ankokuden Hall:

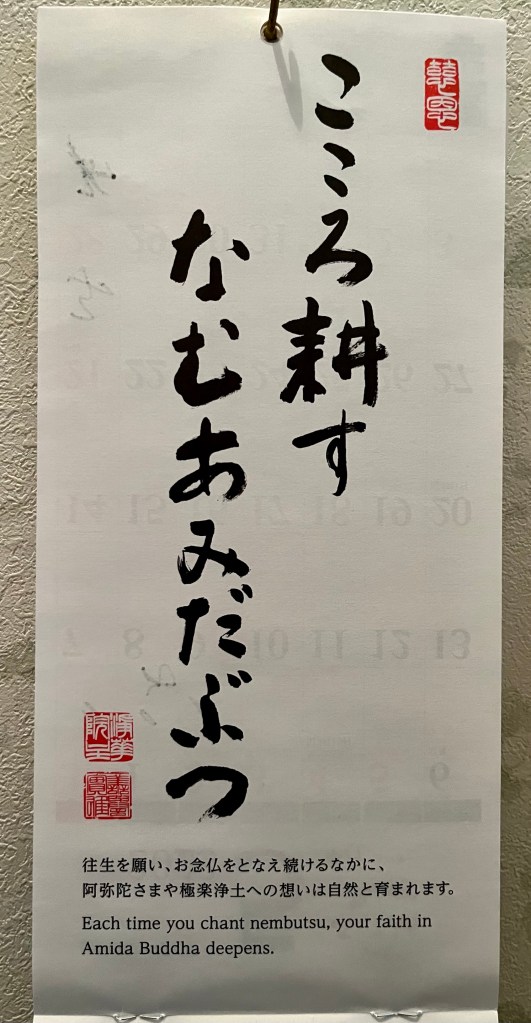

We’ll talk about the museum a bit later. For now let’s focus on the hall. Inside is both a gift shop and another altar to Amida Buddha:

This statue of Amida Buddha is historically significant though: it was the same statue venerated long ago by Tokugawa Ieyasu, the first Shogun of the Edo Period, and final unifier of Japan. This black-colored Amida statue had been a central devotional figure of the Tokugawa Shoguns for generations, so while it’s not the “main attraction” for tourists, from a historical standpoint, it is. I’ve seen it multiple times, and I never get tired of being here.

As alluded to earlier, there are shrines to the left and right of the Amida Buddha. The one on the left is of the founder of the Tokugawa shoguns,2 Tokugawa Ieyasu described above. The one on the right is less clear. It enshrines someone named Princess Kazunomiya. I had to do a bit of research and it turns out that Kazunomiya was a member of the Imperial family (not the Tokugawa family), but had been wed to Tokugawa Iemochi the 14th Shogun as a political marriage intended to heal the centuries old breach between the two families. The arranged marriage had a rocky start, but in the end proved to be a surprisingly happy and successful marriage at a time when Japan was in the waning days of the Shogunate. So, within the Tokugawa family temple, she is enshrined as an important matriarch.

We’ll see more monuments to Princess Kazunomiya shortly, so remember the name.

Anyhow, after picking up some nice incense and another seal in my pilgrimage book, I left the Ankokuden Hall. To its right is a line of statues.

The statue in the front is Bodhisattva Kannon, similar to what we saw earlier.3 There is a small altar to the right as well with another statue of Kannon that is often overlooked:

This is the “Western-facing Kannon”. The western-direction in Mahayana Buddhism is strongly associated with the Pure Land of Amida Buddha (by contrast, the eastern direction is associated with the Medicine Buddha’s own Lapis Lazuli Pure Land), and since Kannon is an attendant of Amida Buddha, this tracks.

But what about the little statues with red bibs?

These statues represent another Bodhisattva named Jizō. I haven’t talked about Jizo as much in this blog, but he’s very important in Japanese religion as a kind of protector deity, especially of children. Each statue adorned with a bib represent a child that was lost in pregnancy or in childbirth, and so the grieving parents pray to Jizo to protect their child in the life beyond. The clothing is an offering to Jizo, perhaps to pass on to the child?

While the statues are very cute, there is a tragic meaning behind them as well.

The line of statues continues back behind the Ankokuden and Hondo (main hall). It is here that you come upon the mausoleum of the Tokugawa Shoguns.

Not all shoguns are interred here. Some are interred in a shrine called Toshogu up north in Nikko. I would estimate that roughly half of the shoguns are interred here. I won’t show them all, since the map and pamphlet you receive at the ticket booth shows a full list. But to give a few examples…

From the mausoleum entrance, if you were to go further left you will see this statue:

Without getting too bogged down in details, the four statues here represent four major Bodhisattvas in the Mahayana-Buddhist tradition. From left to right with Sanskrit (and Japanese) names:

- Manjushri (Monju)

- Avalokitesvara (Kannon)

- Ksitigarbha (Jizo)

- Samanthabhadra (Fugen)

It’s actually quite rare to see all four arrayed like this. I was kind of impressed. It is said these statues were created in the year 1258 according to the plaque.

Further left:

If you go up the stairs and turn right…

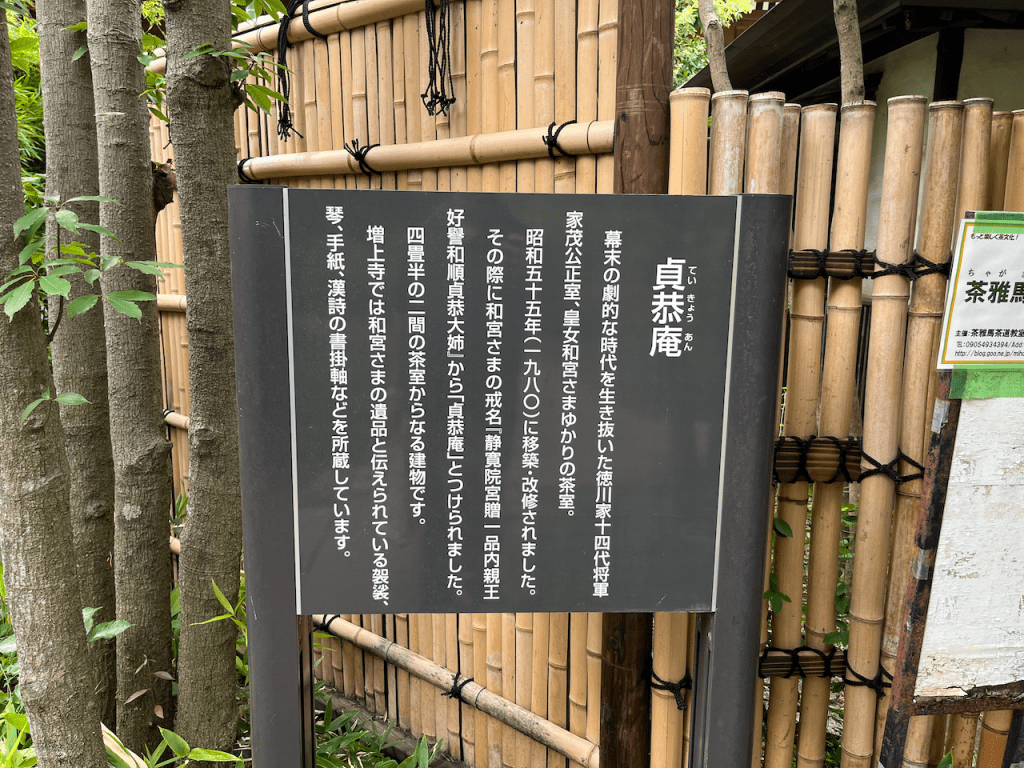

You can find the tea house of Princess Kazunomiya called the Teikyōan (貞恭庵):

Since Princess Kazunomiya took tonsure as a Buddhist nun in her final years, she took the ordination name Teikyo, so the name of the place is basically “Princess Kazunomiya’s hearth”. The sign said that it was refurbished in 1980 and is used for some public functions. It was closed when I came so I didn’t get to see much.

Facing the tea house is another statue of Kannon Bodhisattva in a more motherly form.

Past the tea house and up some stairs is this place, which is the upper part of the map:

It turns out that this is a columbarium: a storage house for the bones of the deceased after cremation. This is common in Buddhist temples. This columbarium in particular houses the bones of those who are somehow connected to the temple across the generations. Beyond that, the website didn’t provide an explanation.

By this point I wanted to see the museum but again I had arrived too early so I stopped by a local McDonald’s for brunch:

On the way out, I also took photos of the Buddhist bell (bonshō 梵鐘) as well:

And a small Shinto shrine to the right of the main entrance:

This Shinto shrine, called the Yuya (熊野) Shrine, was founded in 1624 by the 13th head priest of Zojoji, one Shoyo Kurayama, to protect the north-east corner of the temple from disasters. The north-east is seen as a particularly dangerous direction in Chinese geomancy (a.k.a. feng-shui), so the kami here provide protection. It is not unusual to see small Shinto shrines within Buddhist temples, and many Shinto deities are viewed as manifestations of Buddhist deities (gongen 権現) by Japanese in medieval times. The sign next to the shrine states that 3 kami reside here:

- Ketsumiko-no-ōkami

- Ōnamura-no-mikoto

- Izanagi-no-mikoto (as in Izanagi from early Japanese mythology? I am not sure)

These three kami all seemed to have been imported from a trio of Shinto shrines called the Kumano shrines, which have a strongly syncretic Buddhist-Shinto worship. I didn’t even know the Kumano shrines existed until I wrote this article. Side note: the Chinese characters for Kumano (熊野) can be alternately read as “Yuya”, hence “Yuya Shrine”.

Anyhow, having satiated myself on McD’s, it was time to go back and visit the Museum…

Much of the museum doesn’t allow photography, but showed the history of Zojoji. As it is being restored from earlier destruction, there wasn’t actually that much in the museum.

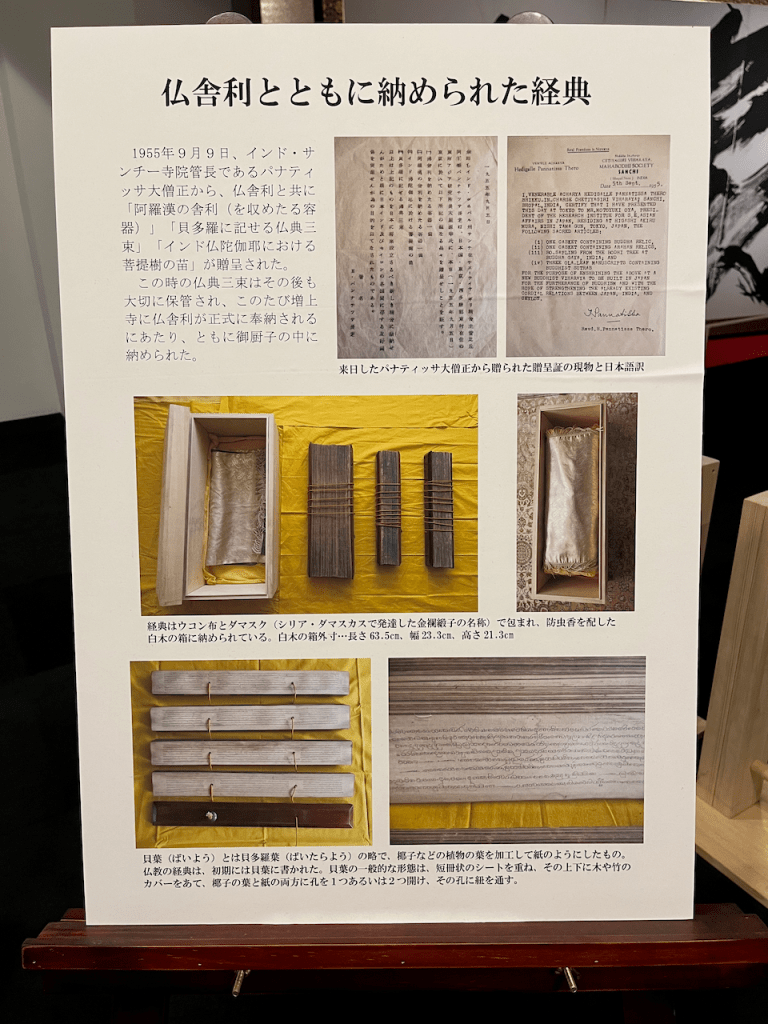

However, what the museum also had (and OK to photograph) was a genuine relic of the Buddha, as in Shakyamuni Buddha, the historical founder. It also contains relics of Rahula, the Buddha’s son before his enlightenment, and Ananda, his trusted retainer. As the sign shows above, the relics were uncovered at Sanchi, which is an important Buddhist archeological site. The relics were given to Japan as a gift in 1955 and enshrined right under Zojoji. You can see

A display to the right shows the contents, and the letter from India to Japan. In addition to fragments of the bones of Shakyamuni Buddha, Rahula and Ananda, the contents included recovered copies of Buddhist sutras that were inscribed on palm leaf at the time, and a seed descended from the original Bodhi Tree.

In my nearly 20-25 years as a Buddhist, I had never come face to face with a relic of the Buddha before, so I was kind of awestruck. The small wooden plaque just in front of the small statue of the Buddha contained a small prayer that reads:

Recite 3 times: namu shaka muni bu (praise to Shakyamuni Buddha)

followed by a longer hymn:

kyo rai ten nin dai kaku son

go ja fuku chi kai en man

in nen ka man jo sho gaku

ju ju gyo nen mu ko rai

(then recite the nembutsu 10 times per Jodo Shu tradition…)

I don’t have a translation of this hymn, but after a bit of late night sleuthing, I suspect it’s a verse from a Buddhist text called the Humane King Sutra. I don’t think there’s an English translation anyway.

In any case, I recited the verses of praise to Shakyamuni Buddha and finally went home.4

But that concluded the trip to Zojoji. Usually, I go with the family, and we can’t afford to spend half a day there, but this time I had some free time and was able to really take in all the sites of Zojoji. As a historical site, Zojoji is very dense and fascinating. It’s hard to imagine centuries of history, all closely tied to the Tokugawa shoguns and the Jodo-shu sect all in one place. The relic of the Buddha alone is pretty amazing too.

This post was pretty long, but I hope you enjoyed.

P.S. I didn’t really provide a lot of links to Jodo Shu Buddhism, since I talk about it quite a bit in the blog already, and many of the English sites have sadly atrophied or disappeared over time. I would definitely recommend various books such as A Raft from the Other Shore or Traversing the Pure Land Path, but these are mostly out of print now. I have done what I could over the years to distill many of these lost sources into an accessible format here, but there’s still plenty to find if you know where to look.

1 This is actually a slang phrase in Japanese too, taken from English: pawaa supotto (パワースポット), meaning any place that inspires you spiritually.

2 Without getting too bogged down in history, think of a shōgun (将軍) as the Imperial-appointed “General Commander of the Armed Forces”. The role has changed and evolved over generations, but suffice to say if you were the shogun, you were the real, not symbolic, authority in Japan.

3 The astute might be wondering why a temple devoted to Amida Buddha also contains so many statues to another figure like Kannon. In Mahayana Buddhism, the two share a close relationship. It is described in the sutras who Amida Buddha is attended to by two Bodhisattvas: Kannon and another named Seishi. Kannon has an outsized following of their own, but the two are frequently depicted together, as both embody the universal goodwill and compassion that are hallmarks of Mahayana Buddhism. Seishi, admittedly, isn’t described much in the Buddhist texts, and thus isn’t revered much on their own.

4 Actually, I stopped along the way at Akihabara because I had never been there. That place was … not for me. Nerdy, but in a very different way. I did have some good fries at a Turkish cafe in Akihabara for dinner, thanks to Mustafa the chef. Very nice fellow. If you are in Akihabara, stop by his cafe and get some good Turkish food.

You must be logged in to post a comment.