My guide book on Japanese culture talks about a concept called sahō (作法), which in a mundane sense just means “instructions” for doing stuff. But the book explains that it also describes how things are done culturally:

… for example, in the case of the tea ceremony, every act is carefully choreographed, from where people sit, to how the water is boiled, to how the ea is prepared and so on.

Again, in the business world, one can observe sahō in action as the seller employs polite language and bows often as he shows various forms of respect to the buyer. Another case would be the social setting of a company, where a subordinate will use particular sahō with his boss.

Page 156

The book further explains:

For most Japanese, sahō is an ingrained pattern of behavior that affects their day-to-day actions without them even being aware of it. However, for people who come from overseas, some of these practices may appear puzzling. Why is someone bowing so many times in a particular setting? Or at another time, why is someone sitting ramrod straight? But for the Japanese, they are simply following the sahō that is appropriate for that place and circumstance.

I definitely experienced some of this confusion in the early years when I visited Japan with my wife. My in-laws kindly took me to a local Takashimaya department store and paid to get me a tailored suit. As a poor white kid in America, the experience was kind of awkward on a few levels: I wasn’t used to getting measured for a tailored suit, I wasn’t used to the very polite speech and mannerisms of the store employee, I wasn’t very good at speaking Japanese, and I wasn’t even used to owning my own suit.1

This concept of sahō isn’t limited to Japanese culture, of course. It is true, based on limited experience, that things can feel really choreographed in Japanese culture compared to American culture, but the idea of “how people do things” is universal. The American handshake is on example, the tendency for Russians not to smile during formal settings, the “pub culture” in Ireland and so on. There’s countless examples unique to each culture.

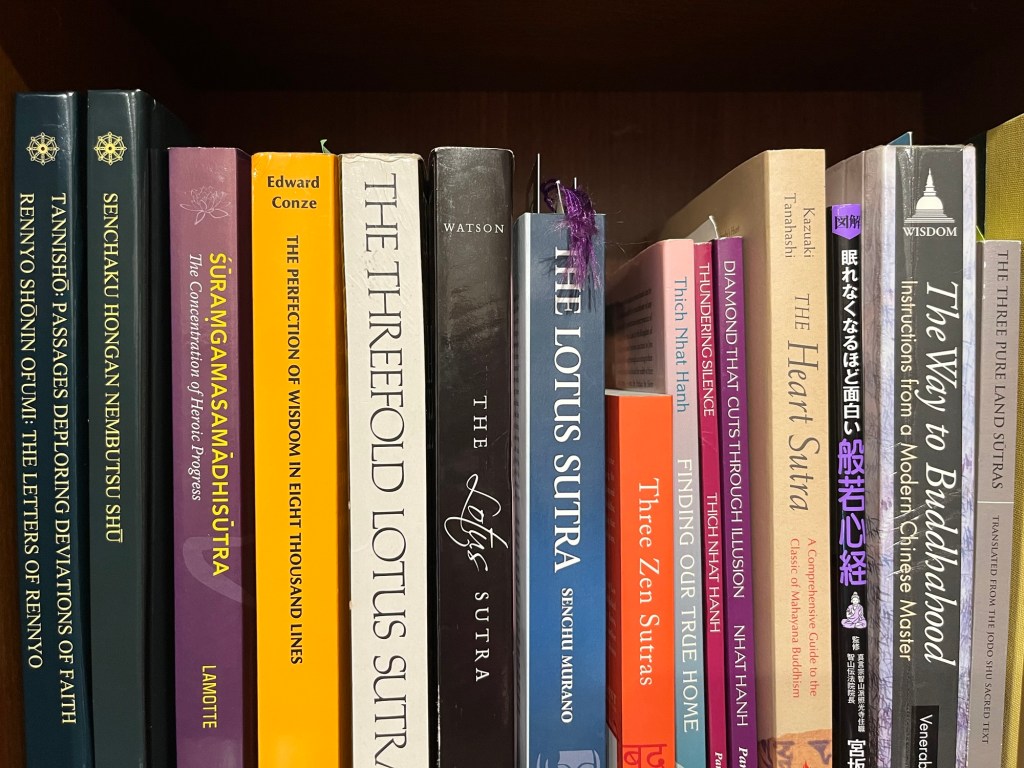

Even for a culture like Japan, where everything really is kind of choreographed, you do get used to it. The extra flourishes at the bookstore (wrapping the books, extra bowing, etc) were a bit confusing at first, but after a while, I don’t even really mind it anymore. Similarly, certain habits became ingrained more and more each time I visit.

So, when you encounter another culture, the important to bear in mind is that each culture has its own sahō, and it will be different than yours. Be observant, be flexible. If you do, you’ll quickly adapt and will succeed. People who stand like tall trees in the wind get blown down, but those who bend like grass prosper.

Food for thought.

P.S. Fun bonus post before Thanksgiving weekend! Happy Thanksgiving Day and Native American Heritage Day to readers in the US.

1 It is still the only suit I own, but I save it for important occasions only, such as my mother-in-law’s funeral. Speaking of sahō, funerals in Japan are very formal compared to American ones.

You must be logged in to post a comment.