A little while back, during my post on Fushimi Inari Shrine in Kyoto, Japan, I alluded to how the native Shinto religion often blended with Buddhism up until the early modern period (e.g. the Meiji Period) when they were more forcefully separated.

You can still see vestiges of this blending in some temples and shrines, but one great example is the Toyokawa Inari shrine right in the heart of Tokyo’s Minato Ward:

This Shinto shrine / Soto-Zen Buddhist temple venerates Dakini-ten (荼枳尼天), which is the Buddhist form of the Shinto kami Inari Ōkami.

Dakini-ten is based on the concept of Ḍākinī in esoteric (a.k.a. Vajrayana) Buddhism, but in Japan it blended with veneration of Shinto kami and thus took on a life of its own.

Anyhow, let’s talk about the temple itself. I visited the temple in 2018 and had little context back then, so I didn’t take as many good photos as I would have liked, but I will try to explain as best as I can.

Once you go past the main gate…

You come upon the main shrine to Inari Ōkami (colloquially known as “O-Inari-san”):

Another, small sub-shrine here:

You can see fox statues all over the complex, due to their close association with Inari Ōkami.

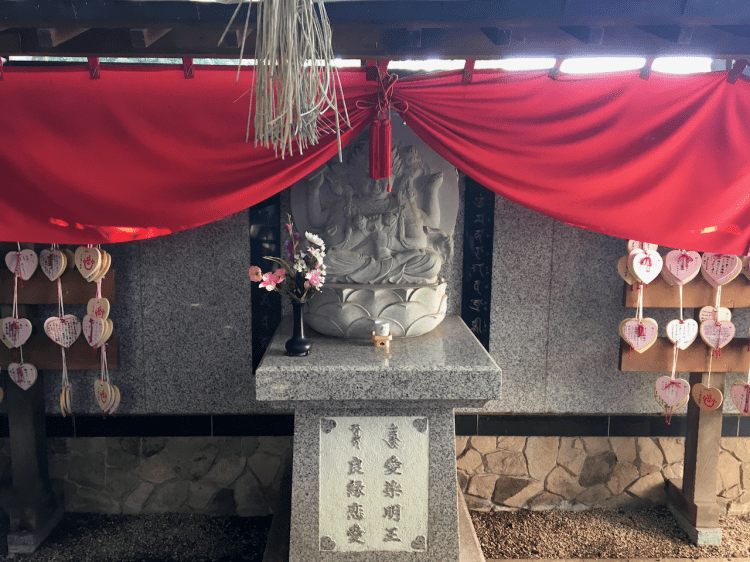

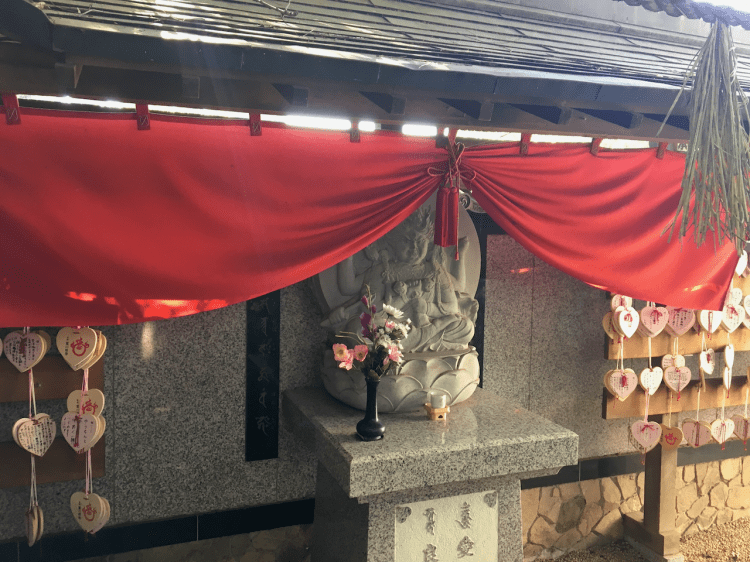

However, other deities, both Buddhist and Shinto are enshrined here too. For example, below is an esoteric-Buddhist (Vajrayana) deity named Aizen Myō-ō (愛染明王):

Also, Benzaiten, one of the Seven Luck Gods:

And Kannon Bodhisattva:

The fact that both Shinto deities like Benzaiten and Inari Ōkami reside in the same shrine as overtly Buddhist deities such as Kannon and Aizen Myō-ō is somewhat unusual, but really isn’t. This was normative for Japanese religion until the modern century. Japan has had two religions for a very long time, and they’ve co-existed for so long, that they often blended together.

If you look at American religion, pagan religion and Christianity co-existed for so long (even when paganism was officially repressed) that the two blended together. Things we take for granted such as Christmas trees, mistletoe, Easter eggs, and such are all examples where they have blended together to religion as we know it today. This might offend religious purists (to be fair everything annoys religious purists), but this is how societies absorb and adapt religions over generations. Japanese culture simply had different religions to work with.

Anyhow, fascinating stuff.

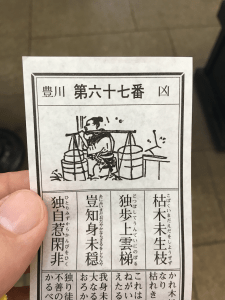

P.S. My omikuji fortune that visit was bad luck (kyō, 凶). I don’t remember having a particular bad year, especially compared to 2020 later, but it was surprising to get an overtly bad fortune for a change.

You must be logged in to post a comment.