Recently while taking my personal retreat, I spent some time catching up on Buddhist reading, and finished a book titled Introduction to the Lotus Sutra by Yoshiro Tamura, and translated to English. I had high hopes for the book, but came away pretty disappointed as it was a pretty thinly veiled promotion of a Nichiren-Buddhist interpretation of the Lotus Sutra, and of Nichiren Buddhism in general.1

One passage makes some interesting comments worth noting though (Wikipedia links added):

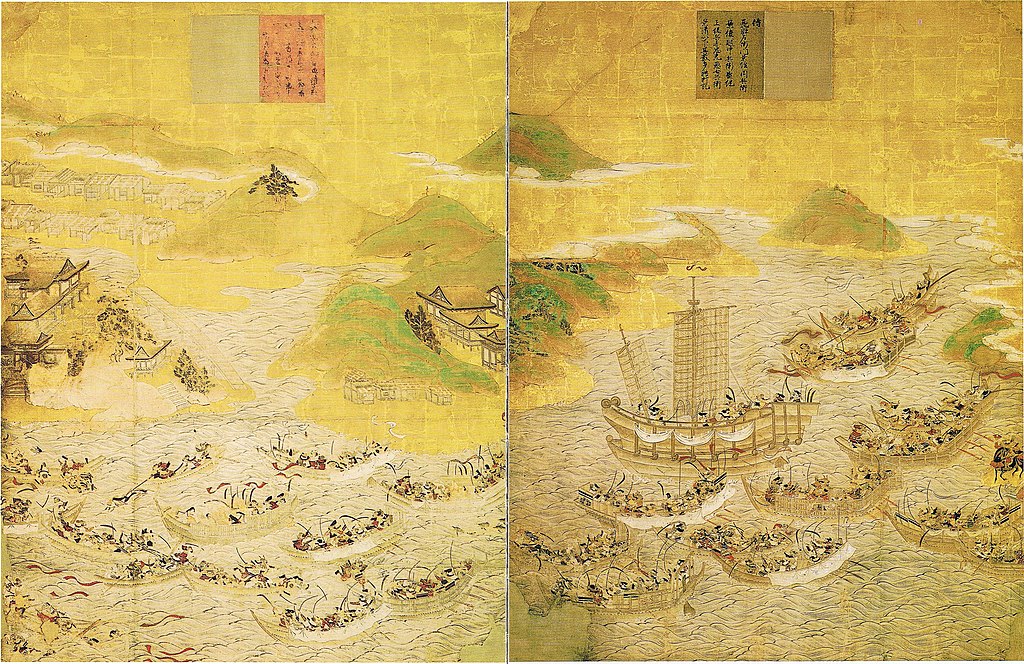

Shinran (1173-1262), Dogen (1200-1253), and Nichiren (1222-1282) also came into reality of out Mt. Hiei’s hall of truth [same as Honen a generation earlier]. Yet their attitudes toward the actual world were quite different from Honen’s. While Honen was mostly devoted to giving up on life and longed for the pure land of the next life, Shinran, Dogen, and Nichiren struggled positively within the actual world. Their activities and writings came right after the Jokyu turbulence of 1221 and were related to it.

Page 123, translation by Michio Shinozaki, edited by Gene Reeves

Mr Tamura is comparing several different Buddhist monks who all left the Tendai sect around the same time, and each founded their own sects. The first, was Honen, who founded the Jodo Shu sect and greatly popularized Pure Land Buddhism in Japan. This is a fascinating historical phenomenon that started in the last 12th century with Honen, and persisted with a couple more generations of Buddhist monks all trained from the same Tendai sect, and apart from Nichiren, its great temple complex on Mt Hiei.

As Nichiren was the last of these great reformers, he had the benefit of hindsight, and tended to be rather harsh toward Honen’s Pure Land movement as degenerate, and further obscuring the true Buddhist teachings (as enshrined in the Lotus Sutra and the Tendai sect). Thus, ever since, Nichiren authors and followers have had particular animus toward Honen. The book doesn’t pull punches either.

But it’s an interesting comment to make, and not without merit. The Jodo Shu Buddhist sect has always been focused on a singular goal within the larger Buddhist religion: to enable followers to be reborn in the Pure Land of Amitabha (Amida) Buddha and thus provide as a refuge, but also to enable them to accelerate on the traditional Buddhist path faster. A lot of this hinges on a medieval-Buddhist interpretation of the “end days” or Dharma Decline, which looks a bit silly knowing what we know now.

In any case, Jodo Shu sect Buddhism, at least on paper, definitely focuses on the life to come. From what I hear on the ground, the reality is a lot more nuanced, and many communities still practice some manner “traditional Buddhism”, but the primary focus still remains rebirth in the Pure Land to come.

So, what Mr Tamura says makes sense.

Mr Tamura is also correct in that Dogen, who founded the Soto Zen sect, and Nichiren approached the same medieval concern with Dharma Decline, but in different ways: Dogen focused on the classic Buddhist approach to mindfulness, meditation, focus on the now, etc. Nichiren took the logical conclusion of the Lotus Sutra’s egalitarian teachings in the form of social reform, nominally as a reform of the Tendai sect, especially in the face of the crooked administration by the new Hojo clan’s military government.2

But I have to disagree with Mr Tamura’s hidden conclusion that by focusing on this-worldly practice that certain sects of Buddhism are superior to others. I feel that this hopelessly generalizes things.

One of the things that always attracted me to Honen’s teachings was his overt rejection of petty, secular life while keeping his focus on the future, namely the Buddha’s Pure Land. It may seem counterintuitive, but by focusing on the “world to come” and thus rejecting the world as it is, i think this fosters a renunciant’s mindset, even as one continues to live in this world. The historical Buddha, Shakyamuni, definitely advocated this approach.

This may seems like not a big deal, especially given other Buddhist sects also have some form of monastic practice, or similar rejection of secular life, but consider that the other aforementioned reformers were all Buddhist monks of hte same Tendai sect, and Tendai at the time had a controversial teaching called hongaku (本覚) or original enlightenment. The idea is that one is already enlightened but unaware of this due to ignorance or skewed viewpoints. This leads to all sorts of thorny issues with Buddhism and Buddhist practice, and gave some scallywags in the Buddhist monastic community an excuse to “loosen the reins a bit” in terms of discipline.

Honen seeing the state of affairs of the community at his time, overtly rejected this concept. Other reformers embraced the concept to some degree or another, sometimes leading to some behavior that in the wider Buddhist world would raise eyebrows.

On the other hand, the historical Buddha definitely advocated practice and mindfulness here and now too. In fact, it’s pretty much central to Buddhist practice, at least for monastic followers. So, Mr Tamura, Dogen, Nichiren and others aren’t wrong.

As a modern 21st-century Buddhist speaking 800 years later (and from another culture), with plenty of personal biases of my own, I think you need a bit of both. On the one hand, whether you are a Buddhist layperson or a monastic, it’s healthy to maintain a renunciant’s mindset. The world is a series of endless transitions, both on a macro level and a personal level, so there’s no lasting refuge or rest. Further, it doesn’t make sense to just throw up your hands and bank on the future through prayer and good merit, because there’s plenty of things you can do in the here and now to make life better for others, and also for yourself. Even if you engage in a little bit of Buddhist practice,3 that’s still a step in the right direction. Even if you meditate even only occasionally, that’s still better than nothing.

So, in a sense, all of the Buddhist reformers in 12th-13th century Japan had something positive to contribute, and each was approaching the same issues with novel approaches. It’s somewhat stupid to try to and hold up one sect as superior to others based on an artificial criteria.

So, anyhow, the book was disappointing, but it does help remind me of what matters.

P.S. Photo taken at the Butchart Gardens in Victoria BC last week.

1 The book started out reasonably well, but the last third of the book was unabashedly promotion of Nichiren Buddhism. Bear in mind that the Lotus Sutra has been revered and influential in many Buddhist communities outside of 13th century Japanese-Buddhist thought, so this tendency to focus on a single sect’s teachings to the exclusion of others. The book’s not-so-subtle tendencies to belittle continental Buddhist culture while promoting Japanese thought didn’t help either. People sure do love to inject culture into their religion.

2 Shinran, who was a follower of Honen, took a more nuanced approach that tends to incorporate some elements of Honen’s view, while focusing on a radically lay-oriented religious community (similar to Nichiren). There’s already plenty of books about Jodo Shinshu (Shinran’s sect), and Shinran, so no need to belabor it here.

3 Consistency has never been my forté. 🤦

You must be logged in to post a comment.