One historical period that has continuously fascinated me for a long time is the end of the Heian Period in Japan, culminating in the climactic war between the Heike (Taira) Clan and the Genji (Minamoto) Clan, followed by the rise of military government for the next 800+ years.

“How did you go bankrupt?” Bill asked.

“Two ways,” Mike said. “Gradually and then suddenly.”

The Sun Also Rises by Ernest Hemingway

Why does this matter?

As the quote above suggests, the fall of the Heian Period and of the Imperial aristocracy, built around a Chinese-inspired Confucian bureaucracy, came slow, then suddenly when the lower samurai class rose and and asserted power. Let’s compare the before and after:

The Latter Days of the Heian Period

The Heian Period (平安時代, 794 – 1185) of Japanese was a long, 400-year period, that began when the Imperial capitol moved to the new city of Heian-kyō (modern day Kyoto) away from Heijō-kyō (modern day Nara). The Imperial government had been plagued with infighting and manipulation by powerful temples in Heiji-kyo, so the Emperor decided to make a clean start and migrate the capitol.

But the earlier Nara Period and the Heian Period represent a single continuum of life in Japan where the Emperor ruled in a Chinese-Confucian style bureaucracy with Japanese characteristics. The Imperial bureaucracy was run by a large number of literate officials either through Entrance Exams that tested your knowledge of the Confucian Classics, and aspects of Chinese history, or through connections if you were nobility.

Speaking of nobility, everyone in the Court, from the lowliest bureaucrat, to the Emperor had an official rank. This was part of the old Ritsuryō system. The Emperor was automatically 1st rank upper (正一位, shō ichi-i), while just below him someone might be 1st rank lower (従一位, ju ichi-i), then 2nd rank upper (正二位, shō ni-i), and so on until you get to the lowly paper-pushing bureaucrat at 少初位下 (shō so-i no ge) rank. Each year, the Emperor would approve promotions or demotions of rank, which would be annouced, so for doing some good work, you might be promoted one year, and your stipend increased, as well as other perks. However, there was a catch. If you were born to a venerable noble family such as the Fujiwara, Ōe or Tachibana, you were automatically 5th rank or higher. If you were not, it was almost impossible to attain anything above 7th rank. Sugawara no Michizane was a rare exception, but he paid for it when court treachery got him exiled.

Thus, the aristocracy held a grip on the Imperial court, but it didn’t stop there. The aristocracy held increasingly large tracts of land called shōen (荘園) that were tax-exempt due to a loop-hole in the system. The wealth of the aristocratic families grew larger and larger while the state became increasingly bankrupt.

Further, as the Heian Period went on, the aristocracy figured out how to manipulate power even further by arranging marriages with the reigning Emperor, and if they had a son, pressure the reigning Emperor to abdicate, so the ambitious family could control the Imperial heir as a regent. Case in point, during the 990’s two different branches of the Fujiwara clan were struggling for control, on led by Fujiwara no Michitaka and the other by Fujiwara no Michinaga. Both them had daughters wed to reigning emperor Ichijō, who had multiple sons. Initially, next reigning emperor was his son Emperor Sanjō who had not been born from a Fujiwara mother, but he was soon pressured to abdicate by Fujiwara no Michinaga, thus allowing Michinaga’s grandson and Ichijo’s other son to become emperor Go-Ichijō (i.e. “Ichijō the latter”) to reign.

Things got even nuttier when certain emperors, forced to abdicate and take tonsure as Buddhist monks, figured out how to retain power behind the scenes at odds with the nobility. The most well known example was Emperor Go-shirakawa who only reigned officially as emperor for three years, but retained power as the “cloistered emperor” for another 37 years.

None of this takes into the account the growing power and political manipulation of Buddhist temples, and their armies of soldiers, an open violation of the Buddhist principle to abstain from politics and violence.

Thus with such a toxic mix of competing power centers, a crippled central government, to say nothing of the earthquakes, plagues and political neglect of the provinces.

… and then it finally started to fall apart.

The Fall

The fall of the Heian Period and its aristocratic society started with a power struggle between the upstart Taira and Minamoto clans. Like many other samurai families, they began as little more than escorts and bodyguards to the nobility, but in time they rose to positions of power and influence, filling in the gaps of government when emperors pushed the Fujiwara back.

This culminated with the dreaded Taira no Kiyomori seizing power in all but name. This grandson, the child Emperor Antoku, technically reigned, but behind the scenes Emperor Go-Shirakawa mentioned above still held to some power, but was effectively a hostage himself. The Minamoto clan were scattered and its clan head was executed for formenting a rebellion.

Kiyomori’s grip on power didn’t last long, and wasn’t long before the his enemies in the provinces began to rally around Minamoto no Yoritomo who led a successful counterattack that resulted in a war across most of Japan, with the Taira (e.g. the “Heike clan”) mostly dominating the west and the Minamoto (e.g. the “Genji”) ruling in the eastern provinces. The current TV drama in Japan, the Thirteen Lords of Kamakura, reenacts this struggle, and the aftermath.

The Taira, including the child emperor Antoku, were wiped out at the battle of Dan-no-ura, but the battles didn’t end there. The genie was out of the bottle, and there was no going back. Minamoto no Yoritomo then seized power by compelling to emperor to recognize him as Shōgun, the generallisimo of all Japan, and he went after rivals within the Minamoto clan including the famous warrior and half-brother, Minamoto no Yoshitsune. He based his regime in the eastern city of Kamakura, not Kyoto, thus drawing power away from the old Imperial court. Emperor Go-shirakawa’s son, Emperor Go-toba, attempted one last military effort to restore the power of the Imperial court in the Jōkyū War, but the samurai class centered around Yoritomo’s widow, the powerful Hojo Masako, and Go-toba’s efforts were doomed. He was exiled until his death.

Ironically, Minamoto no Yoritomo would end his life as little more than a figurehead himself as the Hojo family he married into (ironically a branch of the Taira he defeated) manipulated marriages and increasingly held power.

In the end, the new “Kamakura Period” of history was the first of several military regimes in Japan until 1868 (arguably 1945) where the Imperial court still held nominal power, but true power rested with the military class. The old Confucian-style bureaucracy still existed, people including power warlords still held rank in the Court, but it was a shadow of its former power, and was mainly used to legitimatize the ruling shogun and little else.

On the Ground

Reading this history is one thing, but to people on the ground, as one crisis after another affected Japan during the end of the Heian Period both political and physical, it certainly felt like the End Times.

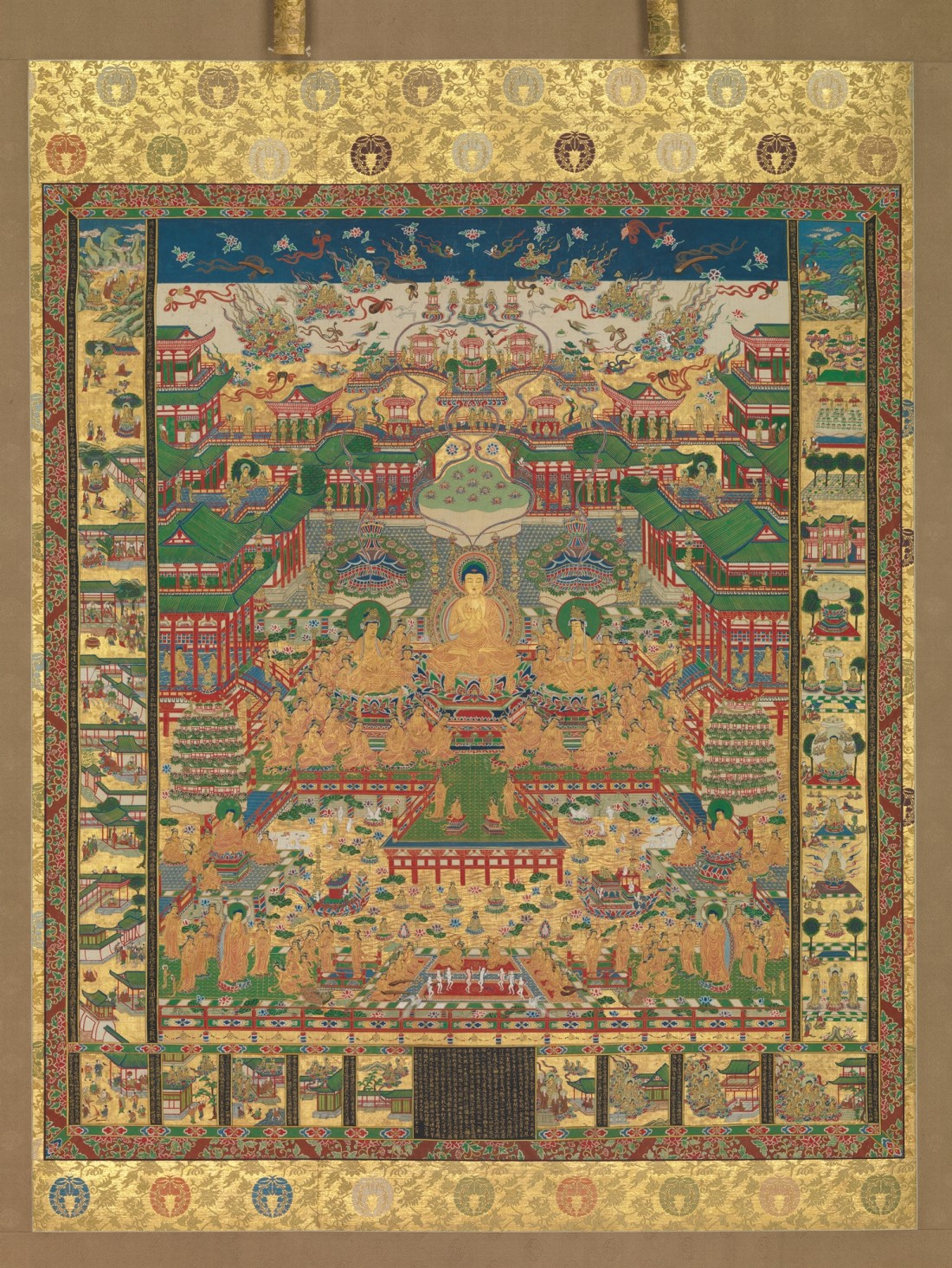

Millenarian Buddhist movements among the provinces sprang up in great number, as people were convinced that the era of Dharma Decline, the era mentioned in Buddhist scriptures when the Buddha-Dharma had utterly faded from the world, had come and that they were all doomed. This is why the Pure Land Buddhist movement started by Honen became so widespread and popular. By this point, people were so convinced that it was all over, they focused on escaping the endless cycle of birth and death to be reborn in the Pure Land of Amitabha Buddha instead. Pure Land Buddhism had been popular before this, but it took on a new sense of urgency under the collapse of the old society. Thus Honen’s disciples, such as Shinran, carried this message further out into the provinces and Pure Land Buddhist movements sprang up everywhere.

Nichiren Buddhism, which came slightly, was a similar millenarian movement, but instead Nichiren blamed society’s ills ironically on the Pure Land movement itself for leading society away from the True Dharma (e.g. the Lotus Sutra). Like many others in society, including Honen a couple generations earlier, Nichiren was appalled by the death, warfare and disasters affecting Japan and felt there had to be a reason for it all.

This may seem odd to us in the 21st century, but for people who grew up that the world around them was governed by the Buddha-Dharma (or lack of it), this is the only conclusion that would make sense. We in our time believe the world is governed by science, so when something happens, we tend to look for a scientific-analytical explanation. When the Byzantines in the 8th century saw their world collapse due to the Plague of Justinian followed by invasions from the new Muslim Arabs, they saw felt that their world that had been governed by God as approaching the End Times too, culminating with the siege of Constantinople itself. Thus, Iconoclasm sprang up soon after.

In each case, people are faced with a cataclysm and are using reason to try to come to grips with what’s going on, and how to fix it. We can look back and laugh and people for their “backward views”, but what will people say about us 1,000 years in the future, I wonder?

The Aftermath

In any case, once the war between the Taira and the Minamoto ended and the capital was moved to Kamakura, life in Japan was simply never the same. Generations had lived with the trauma of last years of the Heian Period, the warfare and so on, and much of the literature of the time including the Hojoki and the Essays in Idleness carry a sense of “paradise lost”. It was over. Everyone knew it, and there would be no going back.

And yet, for all the sadness and sense of loss, Japan did carry on through many subsequent generations to be the country it is today. The court life of the Heian Period is still remembered in things such as the Hyakunin Isshu poetry anthology, doll displays on Girls’ Day, woodblock art, and so on. And of course, historical dramas.

P.S. A scene from the Illustrated scroll of Tale of Genji (11th cent.), depicting the Azuma-ya (“East Wing”). Imperial court in Kyoto, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

You must be logged in to post a comment.