Another dharani I was reading about lately is the Great Compassion Dharani, also known as the Nīlakaṇṭha Dhāraṇī, or in Japanese Buddhism the daihishin darani (大悲心陀羅尼), also known more simply as the daihishu (大悲咒), among other names.

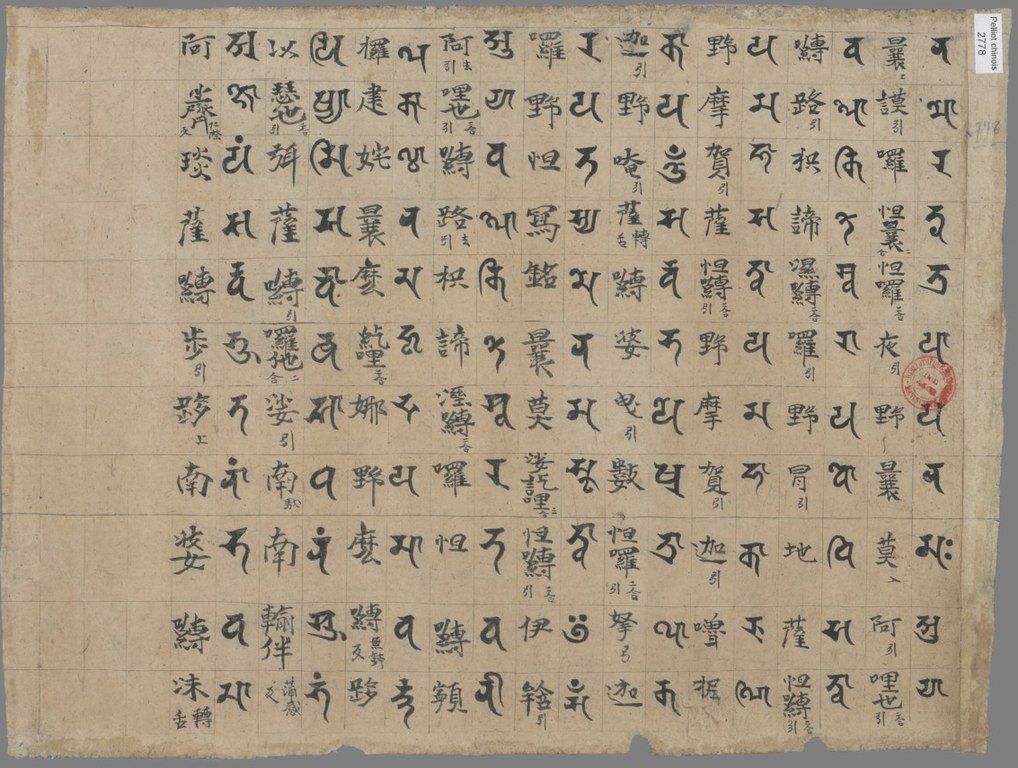

According to Wikipedia, this is one of widely recited dharani across the Buddhist tradition, and has undergone various changes over time, with a couple extant (though corrupted) versions. The featured photo above is an example found in the Dunhuang caves of China, showing the original text in Siddham script, with Chinese transliteration:

You can see another example here, using both Siddham script, and the ancient Sogdian script:

Whereas the Dharani for the Prevention of Disaster (discussed in a previous post) is focused on practical matters, the Great Compassion Dharani is meant to be chanted in order to awaken goodwill towards others, using Kannon Bodhisattva as the archetype. It is taken from a longer Buddhist text, the Sutra on the Thousand-armed, Thousand-eyed Bodhisattva Avalokitesvara’s Sutra of Dharanis on the Vast, Perfect, and Unobstructed Mind of Great Compassion (千手千眼観世音菩薩広大円満無礙大悲心陀羅尼経).

This dharani is most closely associated the Zen traditions, but because it is pretty long, it’s probably not always practical for lay followers to recite in daily services. I have not seen it listed in service books for lay followers in either Soto Zen or Rinzai Zen. In any case, I am posting it here as a reference.

You can see an example of the Great Compassion Dharani being chanted in a formal Soto Zen service here:

There is a nice Chinese-language version here (starts at 1:07):

I have posted the dharani here in multiple languages, so that people can choose which version they prefer to recite. The main source was Wikipedia, but for the Chinese Pinyin, I had to check multiple websites as the pinyin varied slightly in some places, while for the Japanese version, I checked line by line in the video above.

| Sanskrit (Amoghavajra version) | Original Chinese | Chinese Pinyin1 | Japanese Romaji (Soto Zen) |

|---|---|---|---|

| namaḥ ratnatrayāya | 南無喝囉怛那哆囉夜耶 | Nā mo hē là dá nà duō là yè yé | Na mu ka ra tan no to ra ya ya |

| nama āryā | 南無阿唎耶 | Ná mó ā lì yē | Na mu o ri ya |

| valokite śvarāya | 婆盧羯帝爍缽囉耶 | Pó lú jié dì shuò bō là yē | Bo ryo ki chi shi fu ra ya |

| bodhi satvaya | 菩提薩埵婆耶 | Pú tí sà duǒ pó yē | Fu ji sa to bo ya |

| mahā satvaya | 摩訶薩埵婆耶 | Mó hē sà duǒ pó yē | Mo ko sa to bo ya |

| mahā kāruṇikāya | 摩訶迦盧尼迦耶 | Mó hē jiā lú ní jiā yē | Mo ko kya ru ni kya ya |

| oṃ sarvarbhaye sutnatasya | 唵薩皤囉罰曳數怛那怛寫 | Ǎn sà pó là fá yì shù dá nā dá xià | En sa ha ra ha ei shu tan no ton sha |

| namo skṛtva imaṃ āryā | 南無悉吉慄埵伊蒙阿唎耶 | Ná mó xī jí lì duǒ yī méng ā lì yē | Na mu shi ki ri to i mo o ri ya |

| valokite śvara raṃdhava | 婆盧吉帝室佛囉愣馱婆 | Pó lú jí dì shì fó là léng tuó pó | Bo ryo ki chi shi fu ra ri to bo |

| namo narakiṇḍi | 南無那囉謹墀 | Ná mó nā là jǐn chí | Na mu no ra kin ji |

| hriḥ maha vadhasame | 醯利摩訶皤哆沙咩 | Xī lì mó hē pó duō shā miē | Ki ri mo ko ho do sha mi |

| sarva athadu yobhuṃ | 薩婆阿他豆輸朋 | Sà pó ā tuō·dòu shū péng | Sa bo o to jo shu ben |

| ajiyaṃ | 阿逝孕 | Ā shì yùn | O shu in |

| sarvasatā nama vastya namabhāga | 薩婆薩哆那摩婆薩哆那摩婆伽 | Sà pó sà duō ná mó pó sà duō ná mó pó qié | Sa bo sa to2 no mo bo gya |

| mārvdātuḥ | 摩罰特豆 | Mó fá tè dòu | Mo ha te cho |

| tadyathā | 怛姪他 | Dá zhí tuō | To ji to |

| oṃ avalohe | 唵阿婆盧醯 | Ān ā pó lú xī | En o bo ryo ki |

| lokāte | 盧迦帝 | Lú jiā dì | Ryo gya chi |

| karate ihriḥ | 迦羅帝夷醯唎 | Jiā luó dì yí xī lì | Kya rya chi i ki ri |

| mahā bodhisatva | 摩訶菩提薩埵 | Mó hē pú tí sà duǒ | Mo ko fu ji sa to |

| sarva sarva | 薩婆薩婆 | Sà pó sà pó | Sa bo sa bo |

| mālā mala | 摩囉摩囉 | Mó là mó là | Mo ra mo ra |

| mahemahe ṛdayaṃ | 摩醯摩醯唎馱孕 | Mó xī mó xī lì tuó yùn | Mo ki mo ki ri to in |

| kuru kuru karmaṃ | 俱盧俱盧羯蒙 | Jù lú jù lú jié méng | Ku ryo ku ryo ke mo |

| dhuru dhuru vjayate | 度盧度盧罰闍耶帝 | Dù lú dù lú fá shé yē dì | To ryo to ryo ho ja ya chi |

| mahā vjayate | 摩訶罰闍耶帝 | Mó hē fá shé yē dì | Mo ko ho ja ya chi |

| dhara dhara | 陀囉陀囉 | Tuó là tuó là | To ra to ra |

| dhiriṇi | 地唎尼 | Dì lì ní | Chi ri ni |

| śvarāya | 室佛囉耶 | Shì fó là yē | Shi fu ra ya |

| cala cala | 遮囉遮囉 | Zhē là zhē là | Sha ro sha ro |

| mama vmāra | 摩麼罰摩囉 | Mó mó fá mó là | Mo mo ha mo ra |

| muktele | 穆帝隸 | Mù dì lì | Ho chi ri |

| ihe īhe | 伊醯伊醯 | Yī xī yī xī | Yu ki yu ki |

| śina śina | 室那室那 | Shì nā shì nā | Shi no shi no |

| araṣaṃ phraśali | 阿囉參佛囉舍利 | Ā là shēn fó là shě lì. | O ra san fu ra sha ri |

| vsa vsaṃ | 罰沙罰參 | Fá suō fá shēn | Ha za ha za |

| phraśaya | 佛囉舍耶 | Fó là shě yē | Fu ra sha ya |

| huru huru mara | 呼嚧呼嚧摩囉 | Hū lú hū lú mó là | Ku ryo ku ryo mo ra |

| hulu hulu hrīḥ | 呼嚧呼嚧醯利 | Hū lú hū lú xī lì | Ku ryo ku ryo ki ri |

| sara sara | 娑囉娑囉 | Suō là suō là | Sha ro sha ro |

| siri siri | 悉唎悉唎 | Xī lì xī lì | Shi ri shi ri |

| suru suru | 蘇嚧蘇嚧 | Sū lú sū lú | Su ryo su ryo |

| bodhiya bodhiya | 菩提夜菩提夜 | Pú tí yè pú tí yè | Fu ji ya fu ji ya |

| bodhaya bodhaya | 菩馱夜菩馱夜 | Pú tuó yè pú tuó yè | Fu do ya fu do ya |

| maiteriyā | 彌帝唎夜 | Mí dì lì yè | Mi chi ri ya |

| narakinḍi | 那囉謹墀 | Nā là jǐn chí | No ra kin ji |

| dhiriṣṇina | 地利瑟尼那 | Dì lì sè ní nā | Chi ri shu ni no |

| payāmāna | 波夜摩那 | Pō yè mó nā | Ho ya mo no |

| svāhā siddhāyā | 娑婆訶悉陀夜 | Suō pó hē xī tuó yè | So mo ko shi do ya so mo ko |

| svāhā mahā siddhāyā | 娑婆訶摩訶悉陀夜 | Suō pó hē mó hē xī tuó yè | So mo ko mo ko shi do ya |

| svāhā siddha yoge śvarāya | 娑婆訶悉陀喻藝室皤囉耶 | Suō pó hē sī tuó yù yì shì pó là yē | So mo ko shi do yu ki shi fu ra ya |

| svāhā narakiṇḍi | 娑婆訶那囉謹墀 | Suō pó hē nā là jǐn chí | So mo ko no ra kin ji |

| svāhā māranara | 娑婆訶摩囉那囉 | Suō pó hē mó là nā là | So mo ko mo ra no ra |

| svāhā sira siṃ amukhāya | 娑婆訶悉囉僧阿穆佉耶 | Suō pó hē xī là sēng ā mù qié yē | So mo ko shi ra su o mo gya ya |

| svāhā sava maha asiddhāyā | 娑婆訶娑婆摩訶阿悉陀夜 | Suō pó hē suō pó mó hē ā xī tuó yè suō pó hē | So mo ko so bo mo ko o shi do ya |

| svāhā cakra asiddhāyā | 娑婆訶者吉囉阿悉陀夜 | Suō pó hē zhě jí là ā xī tuó yè | So mo ko sha ki ra o shi do ya |

| svāhā padma kastāyā | 娑婆訶波陀摩羯悉陀夜 | Suō pó hē bō tuó mó jié xī tuó yè | So mo ko ho do mo gya shi do ya |

| svāhā narakiṇḍi vagaraya | 娑婆訶那囉謹墀皤伽囉耶 | Suō pó hē nā là jǐn chí pó qié là yē | So mo ko no ra kin ji ha gya ra ya so mo ko |

| svāhā mavali śaṅkrayā | 娑婆訶摩婆利勝羯囉夜 | Suō pó hē mó pó lì shèng jié là yè | So mo ko mo ho ri shin gya ra ya |

| svāhā namaḥ ratnatrayāya | 娑婆訶南無喝囉怛那哆囉夜耶 | Suō pó hē ná mó hé là dá nā duō là yè yē | So mo ko na mu ka ra tan no to ra ya ya |

| namo āryā | 南無阿唎耶 | Ná mó ā lì yē | Na mu o ri ya |

| valokte | 婆嚧吉帝 | Pó lú jí dì | Bo ryo ki chi |

| śva rāya svāhā | 爍皤囉夜娑婆訶 | Shuò pó là yè suō pó hē | Shi fu ra ya so mo ko |

| Oṃ sidhyantu mantra | 唵悉殿都漫多囉 | Ān xī diàn dū màn duō là | Shi3 te do mo do ra |

| padāya svāhā | 跋陀耶娑婆訶 | Bá tuó yě suō pó hē | Ho do ya so mo ko |

Side note, there is a different version in the Japanese Shingon-Buddhist tradition, but I am too lazy to post here, since the dharani is so long. You can find it here on the Japanese Wikipedia article under “真言宗の読み方”.

June 2025: Major rewrite of this page to make the text side-by-side, but also fixed several typos.

1 Sources used to validate the pinyin: here and here, plus Wikipedia article. Each one slightly disagreed with one another, and my Chinese language skills are very limited, so I had to make a best guess in a few cases where things seemingly contradicted. It’s also possible that certain Chinese characters just have multiple pronunciations.

2 For some reason, the Soto Zen version doesn’t have the words 那摩婆薩哆 (nama vastya / ná mó pó sà duō).

3 Similarly, the Soto Zen version doesn’t have the final “om” (唵, ān) in it.

You must be logged in to post a comment.