I have a small fascination with calendars,1 including the traditional Japanese calendar (online example here), which has a lot of interesting cultural tidbits that aren’t obvious to Westerners.

On many Japanese calendars are small words like 大安, 仏滅, and 先勝 that repeat over and over in a cycle each month. These are known as the rokuyō (六曜) or “six days” and are related to a superstition that has persisted since the Edo Period (16th – 19th century).

Here is an old example I took many years ago at my in-laws house in Japan. I use to stare at this calendar all the time, trying to puzzle out what these words meant…

A more contemporary example here is from a calendar we got in 2025:

Prior to the early-industrial Meiji Period (late 19th century), Japan still used a lunar calendar based on the Chinese model which is now called kyūreki (旧暦) or “the old calendar”. As a lunar calendar, it had twelve months, 30 days each, to reflect the cycles of the moon. Japanese New Year thus originally coincided with Chinese New Year, though the first day of the new lunar year is now relegated to kyūshōgatsu (旧正月, “old New Year”). Modern new year is observed on January 1st instead to coincide with Western calendar.

Anyhow, since the months were all exactly 30 days, the rokuyō were six days that reflected good or bad fortune on that day, mainly related to public events like weddings, funerals, new undertakings, etc. Though, it’s thought that the six days were also used to determine one’s fortune in gambling, too. The six days are, in order are:

| Japanese | Romanization | Meaning | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| 先勝 | senshō | Winning first/before | Mornings were thought to be auspicious, but afternoons unlucky. |

| 友引 | tomobiki | Pulling friends | Funerals were avoided this day, but private gathering of friends were considered OK. |

| 先負 | senbu | Losing first/before | Mornings were thought to be unlucky, but afternoons auspicious. |

| 仏滅 | butsumetsu | Death of the Buddha | Inauspicious all day. Social events avoided. |

| 大安 | taian | Great Luck | Very auspicious day. |

| 赤口 | shakkō | Red Mouth | Though 11am to 1pm was thought to be OK, the rest is dangerous, especially handling knives. |

The six days simply repeat over and over throughout the old Chinese calendar, but there’s a twist:

- The first day of the 1st and 7th lunar months is always 先勝 (senshō).

- The first day of the 2nd and 8th lunar months is always 友引 (tomobiki).

- The first day of the 3rd and 9th lunar months is always 先負 (senbu).

- …and so on.

So this cycle of six days actually resets at the beginning of a new month. This leads to some interesting outcomes for certain traditional Japanese holidays, particularly the 5 seasonal holidays or sekku, some of which we’ve talked about here in the blog. For example:

- Girls Day is always 大安 (taian). Girls rock, what can I say? 😎

- Childrens Day (originally Boys Day) is always 先負 (senbu). Maybe boys start out awkward, but mature into their own later? 💪🏼

- Tanabata (July 7th), one of my other favorite Japanese holidays, is always 先勝 (senshō). The star-crossed lovers that feature in the story of Tanabata were separated later, so perhaps they were only lucky at first. 💔 (just kidding)

- Day of the Chrysanthemum (Sept. 9th, another holiday we haven’t gone over yet) is always 大安 (taian). Mathematically this makes sense since it is exactly 6 months away from Girls Day.

Further, a couple other traditional holidays such as jūgoya (十五夜, “harvest moon-viewing day”) is always 仏滅 (butsumetsu) and the lesser-known jūsanya (十三夜, “the full moon after harvest moon”) is always 先負 (senbu).

Finally, there are intercalary or “leap months” (uruuzuki, 閏月) that are inserted about every 3 years to help re-align the calendar with the seasons. Lunar cycles don’t match solar ones very well, so in antiquity, lunar calendars frequently fell out of alignment. In the case of the Japanese calendar, this is done about every 3 years after the risshun season from what I can see.

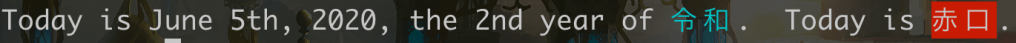

A while back before I had all this figured out, I wrote a small computer program that would execute every time I would log into my computer terminal. Sometimes, I written program this in Python language, sometimes in Ruby, and then Golang. The screenshot below is from the Ruby version which worked reasonably well:

The current incarnation I use was written in Golang language and doesn’t yet include Imperial reign name, nor leap months. I have taken the existing version and moved it to Gitlab for public usage, though it is far from complete. You can find the repo here.

Anyhow, that’s a brief look at the rokuyo in the Japanese calendar. If you’re technically-inclined, feel free to try out the program above, make improvements, send feedback, whatever.

For everyone else, the six days are a bit of a cultural relic from an earlier time in Japan, and apart from planning weddings and funerals, most people give it no real thought. Me? I like to check it from time to time and see if my day’s experiences matched the day’s fortune (spoiler: it usually doesn’t).

Edit: turns out my Ruby code had a silly bug in it all these years. It is now fixed.

Edit 2: turns out 2023 in the Chinese lunar calendar had a leap month, which throws off this entire script. I hadn’t expected this. Will think about this for a while and try to solve for leap months too.

1 Historia Civilis has a fun video on Youtube about the origin of the Julian Calendar and why 44 BCE was the “longest” year in history.

2 The idea of the Buddha’s death and the concept of Nirvana (lit. “unbinding”) is a lengthy subject in Buddhism. Enjoy!

You must be logged in to post a comment.