Not too long ago, I found an old book I had forgotten I had: a translation of the Awakening of Faith in the Mahayana. For simplicity, we’ll call it the “Awakening of Faith” in this blog post. The Awakening of Faith is a Buddhist treatise, a śastra,1 written probably in the 6th century, but attributed to a Buddhist master in India, Aśvaghoṣa from the 2nd century. It is thought to have been composed in China, but likely drew from Indian sources, or was composed by an Indian-Buddhist monk living in China. Since it is mainly found in China, it is called Dàshéng Qǐxìn Lùn (大乘起信論).

Wikipedia points out that researchers now think a more appropriate title would be Awakening of Mahayana Faith in the Suchness of the mind. The 信 here might also be interpreted as “trust” or “entrusting”, so maybe Awakening of Mahayana-style Entrusting [in the Suchness of the Mind]? That reads a bit awkward though, so readers will have to decide how to phrase it.

If readers are curious what Mahayana Buddhism is, please feel free to read here.

This might sound like I am splitting hairs, but it is kind of important to emphasize that English terms like “faith” aren’t a good analogue for what the book is about. This is not a book of Christian-style faith. Instead, the author of the treatise addresses why they wrote The Awakening of Faith, when the same teachings are found throughout existing Mahayana sutras:

Though this teaching is presented in the sutras, the capacity and deeds of men today are no longer the same, nor are the conditions of their acceptance and comprehension….

Translation by Yoshito S. Hakeda

The author lists eight reason such as helping all attain peace of mind, liberating from suffering, and correcting heretical views (my words, not the book). In other words, the author wanted to both assert an orthodox Mahayana viewpoint of Buddhism, but also to clarify any misunderstandings and inspire others to take up the path. It is in a sense, a textbook introduction of Mahayana Buddhism.

Mahayana Buddhism is actually a pretty broad tradition, with lots of sub-schools, diverging viewpoints and so on. So, it’s hard to explain the entire tradition in a single book. Still, the treatise does a good job of touching on some essentials that many Mahayana Buddhist traditions today are founded upon. Traditions such as Zen, Pure Land, Nichiren, Tendai, and Vajrayana (among others) all have certain common teachings that pervade them all. The Awakening of Faith helps to enumerate what these are, in a fairly short, readable format, which for a 6th century text is pretty impressive.

To give an example, here is a quote on Suchness : a fancy term for reality, totality of existence, the Whole Enchilada, the Whole Shebang, etc, etc.:

[The essence of Suchness] knows no increase or decrease in ordinary men, the Hinayanists [earlier Buddhist schools], the Bodhisattvas, or the Buddhas. It was not brought into existence in the beginning, nor will it cease to be at the end of time; it is eternal through and through.

Page 65, translation by Yoshito S. Hakeda

If this sounds strangely familiar to readers, you might find something very similar in the Heart Sutra:

“Hear, Shariputra, all dharmas [all things, stuff] are marked with emptiness; they are neither produced nor destroyed, neither defiled nor immaculate, neither increasing nor decreasing….”

Translation by Ven. Thich Nhat Hanh in “Heart of Understanding”

You can definitely see some common themes between The Awakening of Faith and early Mahayana-Buddhist sutras such as the Heart Sutra. Further, The Awakening of Faith explores the notion of Bodhisattvas quite a bit:

The Buddha-Tathāgatas [e.g. the many buddhas], while in the stages of Bodhisattva-hood [i.e. on the cusp of becoming fully enlightened buddhas], exercised great compassion, practiced pāramitās [perfecting certain virtues], and accepted and transformed sentient beings. They took great vows, desiring to liberate all sentient beings through countless aeons until the end of future time, for they regarded all sentient beings as they regarded themselves.

Page 67, translation by Yoshito S. Hakeda

… but it gradually moves from theoretical teachings into more practical ones too. I was surprised to see the treatise openly teach the importance of developing faith in the Western Pure Land of Amida Buddha:

Next, suppose there is a man who learns this teaching for the first time and wishes to seek the correct faith but lacks courage and strength….It is as the sutra says: “If a man meditates wholly on Amitābha Buddha in the world of the Western Paradise and wishes to be born in that world, directing all the goodness he has cultivated [toward that goal], then he will be reborn there.”

Page 103, translation by Yoshito S. Hakeda

The particular “sutra” that the author is talking about is unclear. Hakeda and other scholars seem really quick to dismiss this section as a later addition, or influenced by the Pure Land Buddhist community, since it’s not found in the Three Pure Land sutras, but I would argue that it is either quoted from, or related to an earlier Pure Land sutra called the Pratyutpanna Sutra. Note this quotation here:

In the same way, Bhadrapāla, bodhisattvas, whether they are ascetics or wearers of white (i.e., laypeople), having learned of the buddha field of Amitābha in the western quarter, should call to mind the buddha in that quarter. They should not break the precepts and call him to mind singlemindedly, either for one day and one night, or for seven days and seven nights. After seven days they will see Amitābha Buddha. If they do not see him while in the waking state, then they will see him in a dream.

Translation by Paul Harrison, courtesy of BDK America

But I digress.2

If you think of The Awakening of Faith as a kind of Mahayana training manual, you’d probably be right. It’s meant to distill the vast corpus of teachings into a more bite-sized treatise that covers all the important bases without getting bogged down in sectarian debates. It’s not difficult to read, but does get a little cerebral at times. Still, it was a pretty impressive effort for the day, when Buddhism was still being introduced in China, and people wanted sought to find a way to make the teachings accessible and easy to understand.

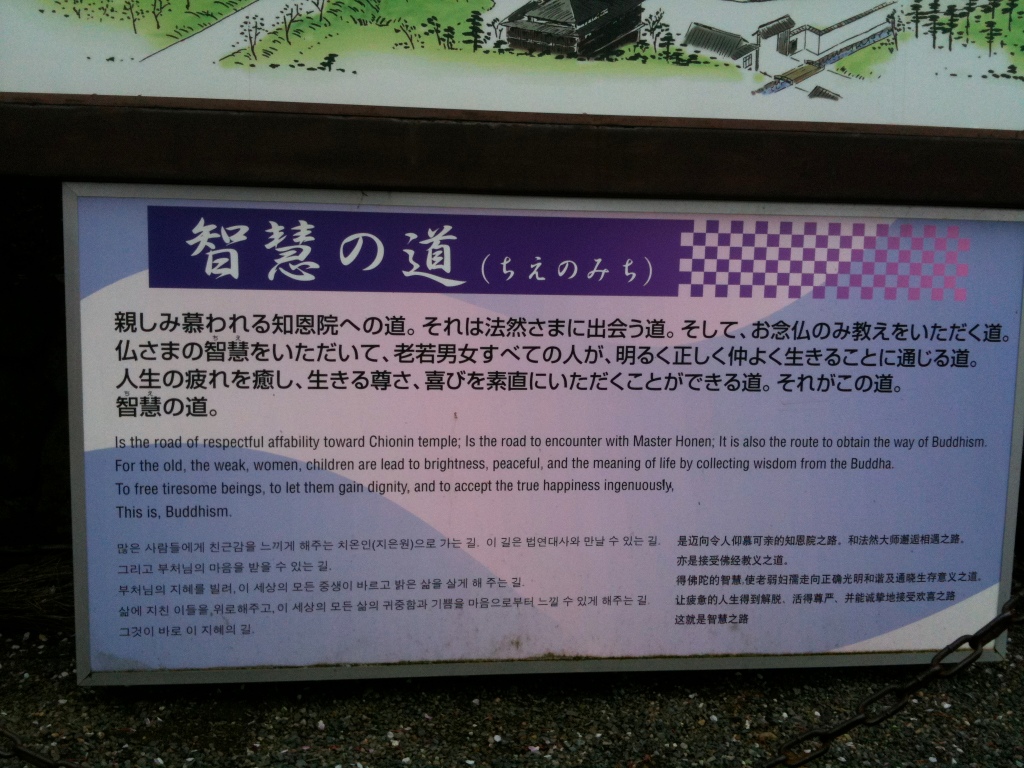

It’s influence on later East Asian Buddhism cannot be understated. It provided an important foundation for later schools such as Tian-tai (Tendai in Japan), and subsequent schools that arose from it: Zen, Pure Land, etc.

English translations are hard to find, but if you manage to find a copy of The Awakening of Faith, and are interested to understand what Mahayana Buddhism is all about, definitely pick it up.

1 Pronounced like “shastra”, see Buddhist Sanskrit Basics for more information.

2 It’s quite possible that Professor Hakeda is correct in that it’s a later addition. Ph.D’s aren’t for show: the dude has a lot of background and training in the subject, so he knows a lot. I just think that because the Pratyutpanna Sutra was already popular in China by the time that The Awakening of Faith was composed, it might not be a later addition. But as the kids say, that’s just my “head canon”. 😁

Also noteworthy is no mention of the verbal nembutsu in the above quote. The verbal nembutsu as a practice was popularized centuries later by Shan-dao. Therefore, if it was added to The Awakening of Faith as an afterthought, it was probably something very contemporary.

You must be logged in to post a comment.