There’s a good chance that if you ever visited Tokyo, you’ve been to this place:

This place is Asakusa Temple, or in Japanese Asakusa-dera, though more formally known as Sensōji. The Chinese characters 浅草寺 can be read either way. This is a temple formerly of the Tendai sect that has been a part of Tokyo since at least the 9th century and is centered around a statue of the Bodhisattva Kannon said to have washed up on the shore one day. The homepage (English available) is here.

Asakusa Temple is simultaneously a giant tourist-trap and a great experience. I have visited the temple 3-4 times since 2009 and it is always worth it. I have included photos from various trips below.

The first thing people will see is the famous Kaminari-mon Gate (雷門, “the lightning gate”) with its massive red lantern, flanked by two guardian Buddhist deities, the Niō. If you pass through the gate, or on your way out, you may notice the reverse:

The lantern on the back instead reads Fūraijinmon (風雷神門) or the Gate of the Wind and Thunder god.

Once you pass through the gate, you will see a huge, long walkway: the Nakamise-dōri (中店通り):

This is not the temple proper. This is a large number of very crowded street stalls selling all kinds of wares: some focused on foreign tourists, and some focused more on native Japanese visitors. You can find all kinds of things here. In our most recent trip, we found some excellent shichimi spice with yuzu flavor added. Goes really well in soups. You can probably spend half a day here. Just beyond these shops, to the left and right, are various restaurants, against catered toward either native Japanese or foreign tourists. We ate at this place during our last trip:

In any case, once you go all the way past the shops, you can get to the temple proper:

This tall structure is a pagoda:

A pagoda, or gojū no tō (五重塔) in Japanese, is something adapted from Chinese culture and is meant to represent the ancient Buddhist stupas in India: storehouses for relics of the Buddha.

The temple gate itself, called the Hōzōmon (宝蔵門, “treasure [of the Dharma] storehouse gate”) sports a similarly large red lantern:

Past this second gate you are now at the temple proper. There is a large, outdoor charcoal brazier with incense sticks burning here. Per Buddhist tradition, you can purify yourself (ablution) before seeing the Bodhisattva by waving some of the incense smoke over you. Once ready, you then proceed to the main hall (honden 本殿):

If you look up as you pass this lamp, you’ll also see the underside has a neat dragon pattern on it:

Since the temple itself is devoted to the Bodhisattva Kannon, you will see it enshrined at the central altar:

The statue itself is hidden behind the red screen, but is flanked by two other statues denoting the Indian gods Brahma and Indra as guardians. Also, if you pay attention, you’ll notice this mark both on the red screen and above:

This is the Sanskrit letter “sa” written in old Siddham script as 𑖭, and is used to represent Kannon. It also represents the Sanskrit word satya (“truth, virtue, etc”). There is also a really large grilled wooden box in front, and that is where you can put in a donation. Per tradition, people often put in a ¥5 yen coin (go-en-dama) due to word-play that implies fostering a karmic-bond with the bodhisattva.

Note that if you go left of the main hall, there’s several other things to note. First is the koi pond and bridge:

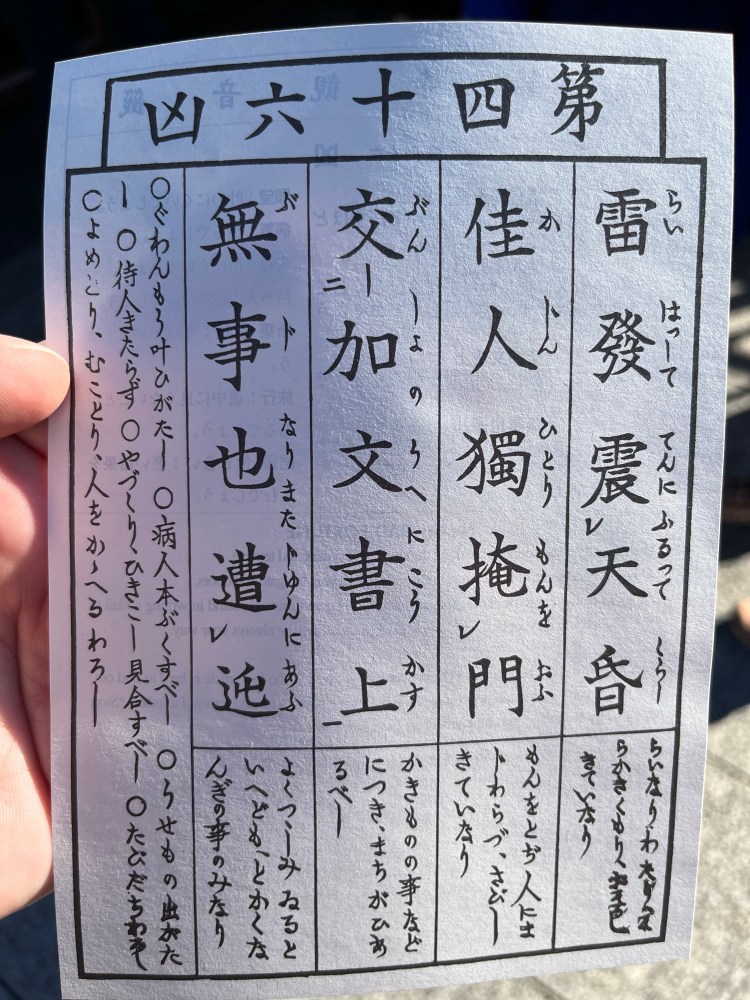

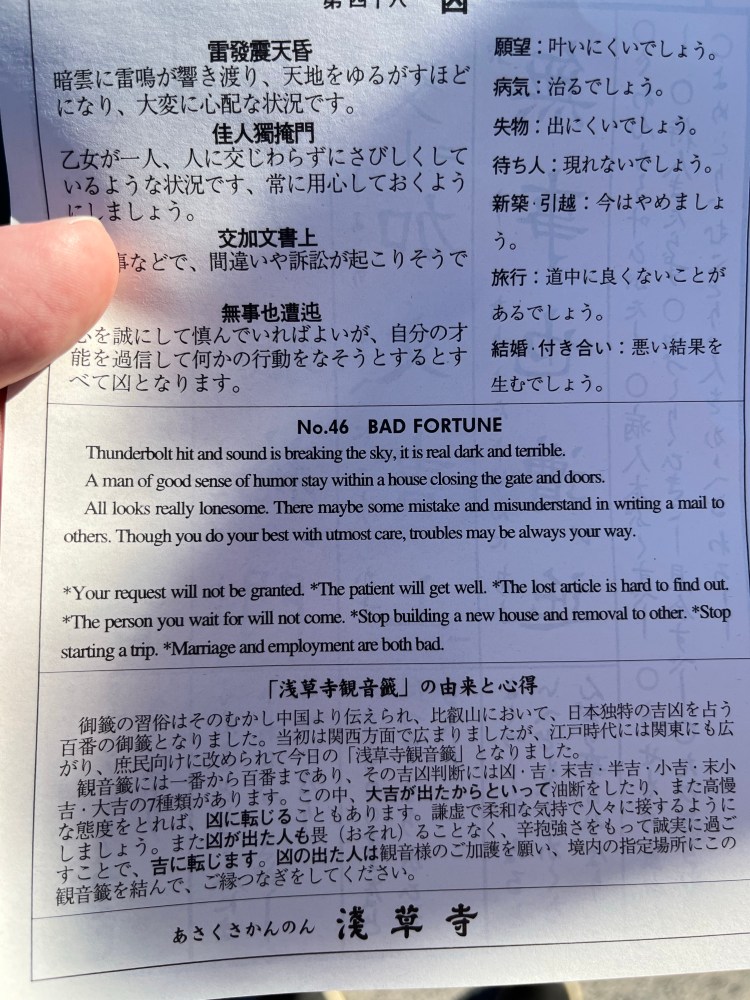

There’s also a place here where you can draw your fortune (omikuji). This year, I drew a bad fortune (凶 on the upper left):

Per tradition, if you get a bad fortune, you’re supposed to tie it up on a small wire fence nearby, so the bad luck “stays there”, and does not follow you.

There is also a statue of Amitabha Buddha (阿弥陀如来, amida nyorai) nearby:

Finally, to the left of the main hall is one of several secondaries halls that compromise the temple complex. This hall is called the Yogodo Hall:

It is here that I got my pilgrimage book in 2022:

The Yogodo Hall is a commemorative hall to mark the 1,200th anniversary of the Tendai monk Ennin, who was a pivotal figure in the early Japanese Tendai tradition, and still crucial to the growth and development of the tradition. Side note, the term yōgō (影向) is a Buddhist term of the temporary manifestation of a Buddha or Bodhisattva or other divinity in the world for the benefit of beings. This is probably meant to be a form of praise to Ennin, implying that he had been a temporary manifestation of a Buddhist figure.

There are several other halls I’ve managed to overlook each time I visit, but a full map of the site in English can be found here.

In any case, it’s interesting to look back on my old photos and reflect on how much has changed (phone camera technology, for example 😉 ), and how much has remained the same at Sensoji…

You must be logged in to post a comment.