This blog, and its blogger, have focused on the Pure Land tradition of Buddhism for many years. I didn’t really start practicing Buddhism seriously until I encountered the Jodo Shu-sect teachings of Honen way back in 2005. It really inspired something in me that’s never stopped even as my practice has taken many twists and turns.

But, strangely, I’ve never actually talked about what a “pure land” is. That’s the subject of today’s post.

The concept of a “Buddha land” or “Pure land” is actually a broad and rich tradition within Mahayana Buddhism, and well worth exploring. Here, I am not talking just about Amida Buddha and his Pure Land, but the general concept. It shows up a lot in Mahayana Buddhism and its many traditions, including the Zen tradition. It also shows up in contemporary Asian literature as well, including Akutagawa Ryunosuke’s famous short story “The Spider’s Thread” (蜘蛛の糸) as well as the Legend of Zelda series. Once you recognize it, references to Buddha lands show up in many unexpected places.

And yet, it all started long ago in India.

Traditional cosmology (i.e. “how the world is arranged”) in India tended to see a flat world with continents strung together in all directions, including above and below. Some of these continents would be anchored by a massive mountain in the middle, called Mount Sumeru (or Mount Meru). You can see this also in Buddhist architecture such as this famous temple in Bangkok, Thailand:

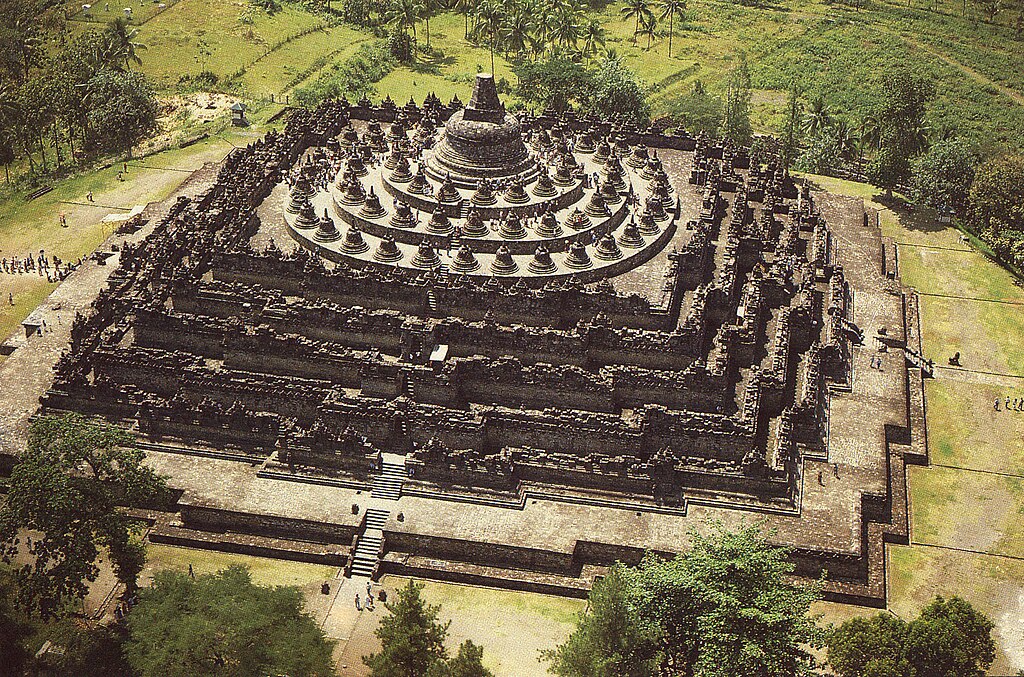

Or the famous Borobudur temple in Indonesia:

Incidentially, people in India thought that they lived in one of these continents called Jambudvipa, which was on the southern end of Mount Sumeru. For example, in the Earth Store Bodhisattva Sutra, you see text like so (chapter 4):

Thus, in this Saha world, on the continent of Jambudvipa, this Bodhisattva teaches and transforms beings by means of millions of billions of expedient devices.

Translation by City of Ten Thousand Buddhas

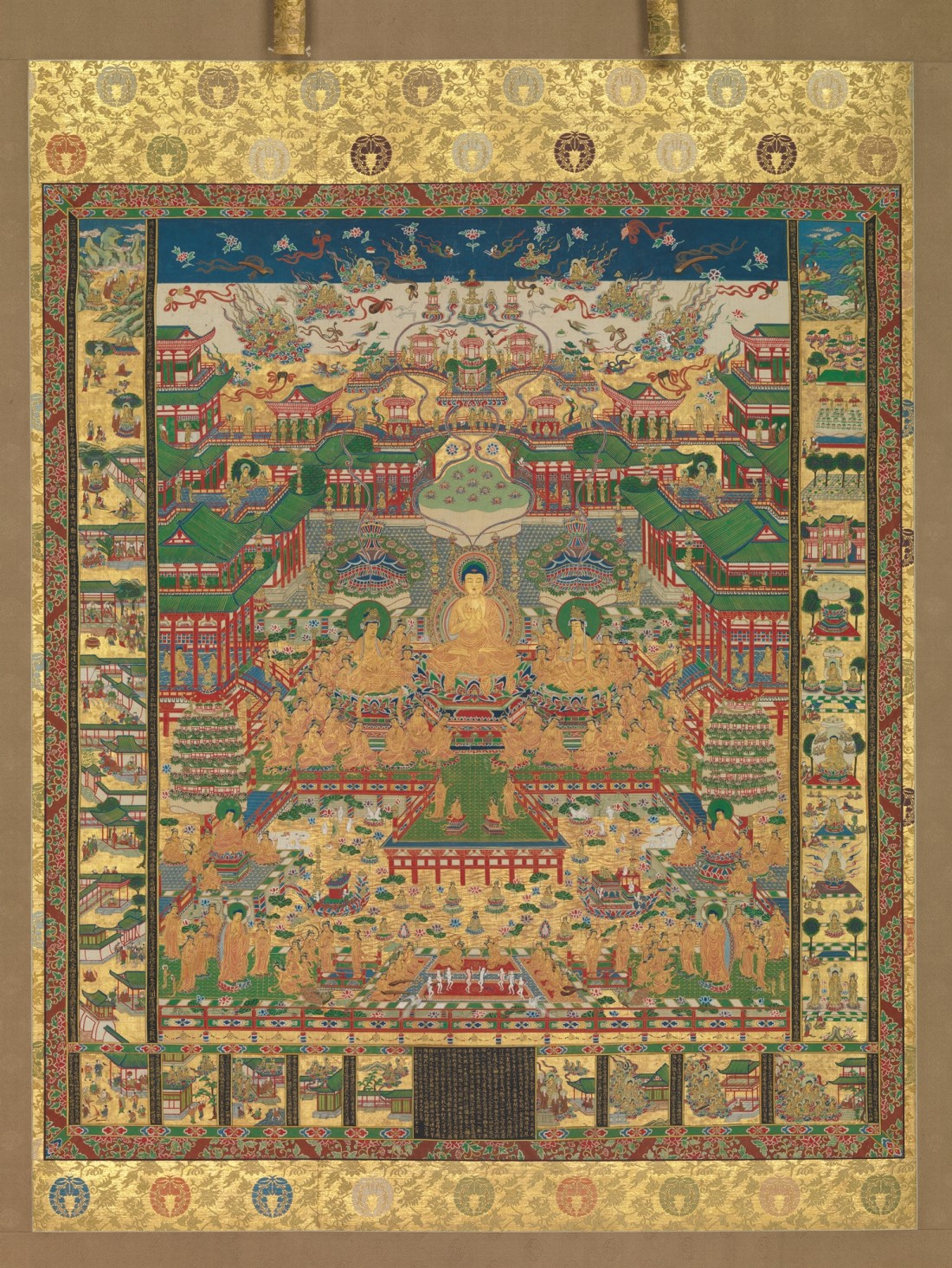

Anyhow, different continents were more peaceful and civilized than others. In some continents dwelt a living buddha, and by their sheer presence, the land would be purified, and all would be peaceful. Such lands are called buddhakṣetra in Sanskrit.

Let’s take a look this passage from the Amitabha Sutra:

At that time the Buddha told the Elder Shāriputra, “Passing from here through hundreds of thousands of millions of Buddhalands to the West, there is a world called Ultimate Bliss. In this land a Buddha called Amitābha right now teaches the Dharma

Translation by City of Ten Thousand Buddhas

In this sutra, the Pure Land of Amitabha is just one of many such lands that exist to the west, but a particularly splendid Buddha land. Buddhas and Buddha lands were thought to exist in all cardinal directions, and the Amitabha Sutra above goes to great lengths to describe some of them, but highlights Amida Buddha’s Pure Land in particular.

Another example of a Buddha land is the realm of the Medicine Buddha, called Lapis Lazuli, which was thought as existing to the east (not west). The Medicine Buddha Sutra describes it at length. It even goes out of its way to say it’s easier to be reborn in the realm of Lapis Lazuli than the Pure Land of Amitabha:

“If their rebirth in the Pure Land is still uncertain, but they hear the name of the World-Honored Medicine Buddha, then, at the time of death, eight great Bodhisattvas, namely, [list of names] will traverse space and descend to show them the way. They will thereupon be reborn spontaneously in jeweled flowers of many hues. [i.e. be reborn in the Buddha land of the Medicine Buddha]

Translated and annotated under the guidance of Dharma Master Hsuan Jung by Minh Thanh & P.D. Leigh

If a person could be reborn in their next life in a Buddha land, any Buddha land, and thus be in the presence of a living Buddha, it is thought they would find refuge, but also they would advance much better along the Buddhist path. The idea of Pure Lands never supplanted or replaced more tradition Buddhism, but if your current circumstances prevented you from following the Buddhist path, you could opt to be reborn in a Buddha land and make up for it in the future.

… but then we come to another Buddha land worth noting: the Buddha land of Shakyamuni Buddha himself. The sixteenth chapter of the Lotus Sutra drops a plot twist wherein the Buddha never really died, and exists for all time on Vulture Peak in India (a real place where historically he and the Buddhist community often dwelt), and preaching the Dharma to any who see him (details added by me in parantheses):

I live on Mt. Sacred Eagle (another name for Vulture Peak)

And also in the other abodes

For asaṃkhya (countless) kalpas (eons).…”This world is in a great fire.

Translation by Rev. Senchu Murano

The end of the kalpa [of destruction] is coming.”

In reality this world of mine is peaceful.

It is filled with gods and men.

The Lotus Sutra version of the Pure Land is less about esoteric geography, and more about Shakyamuni Buddha always being here, whether we see them or not. It comes down to wisdom, clarity, and good conduct.

This viewpoint is found in Zen as well. When we look at the Hymn of Zazen by Japanese monk, Hakuin, who was a lifelong devotee of the Lotus Sutra, we can see the influence:

浄土即ち遠からず

Amateur translation by me

Jōdo sunawachi tōkarazu

“Indeed, the Pure Land is not far away”

and:

当所即ち蓮華国此身即ち仏なり

Amateur translation by me

Tōsho sunawachi rengekoku, kono mi sunawachi hotoke nari

“This place is none other than the Land of Lotuses [the Pure Land],

this body is none other than the Buddha.”

But this isn’t just Hakuin talking. As we saw with the Obaku Zen tradition (a cousin of Hakuin’s Rinzai tradition), they felt the same way, only replacing Shakyamuni with Amida Buddha. But the sentiment was the same. You’ll find similar sentiments in esoteric traditions too, but I have little experience with those and cannot explain in much detail.

So, that brings us to the point: how does one interpret all these Pure Lands, these Buddha lands? My views have gradually changed over time, but I don’t pretend to have the answer. I think in a way that all viewpoints are correct. It is like the famous parable of the blind men describing an elephant: everyone has some idea, but the big picture is beyond our grasp. So, there’s no wrong way to interpret it. If one believes it’s a faraway refuge to be reborn into, that’s totally fine.1 If one believes it’s all in the mind, that’s fine too.

Even the Buddhist sutras, including some I linked above, state that simply “hearing” of the Buddha lands is a merit unto itself. So, if you’ve made it this far, you’re already doing just fine. Just apply the teachings in the way that best fits you.

Namu Shakamuni Butsu

Namu Amida Butsu

1 Maybe this is my background as a scifi fan or something, but I do like to imagine that instead of physical continents, the various worlds and Buddha lands are just planets and worlds across the entire Universe. But that’s a personal view, more fantasy than firm belief, so please take it with a grain of salt.

You must be logged in to post a comment.