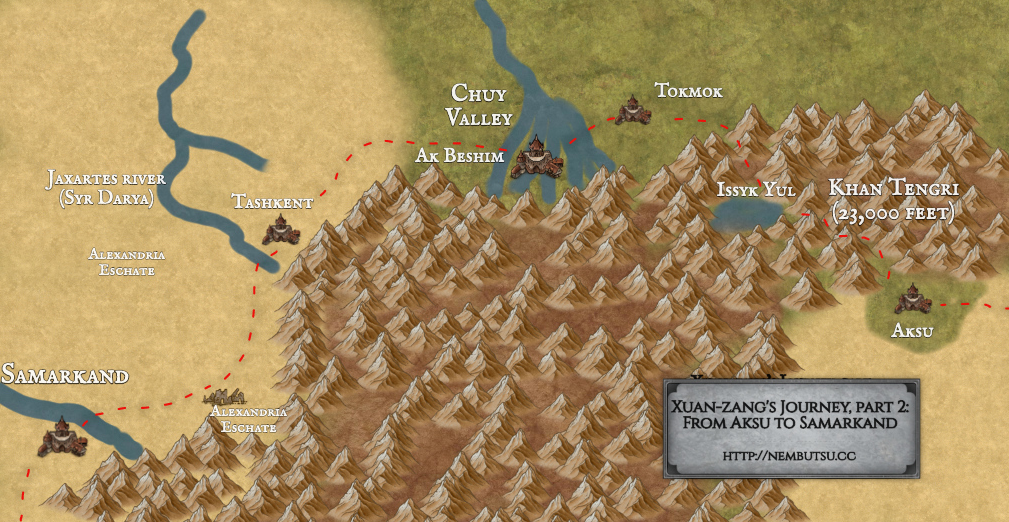

In part one, Xuan-zang the famous Buddhist monk of the 7th century who crossed from China to India encountered the first cities of the Silk Road, crossed the Gobi Desert, and avoided bandits and overbearing monarchs. In part two, Xuan-zang journeyed to the famous city of Kucha and climbed the mountain pass near Tengri Khan losing many people in the dangerous crossing.

As Xuan-zang traveled further and further west, he was leaving Chinese political influence and going further into areas comprised of steppe nomadic tribes such as the Turkic people, as well as sedentary Iranian people such as the Sogdians.

But let’s talk about Turkic people for a moment.

As we’ve talked about in previous posts, the Silk Road was a fascinating mix of different cultures and people. This was very common in the nomadic world of the Eurasian Steppes because tribes were constantly moving around, encountering new tribes, subjugating new tribes, being subjugated by other tribes, or forming alliances. It was a very fluid, dynamic and extremely dangerous environment. We’ve seen examples in past blog posts with groups like the Scythians and Parthians.

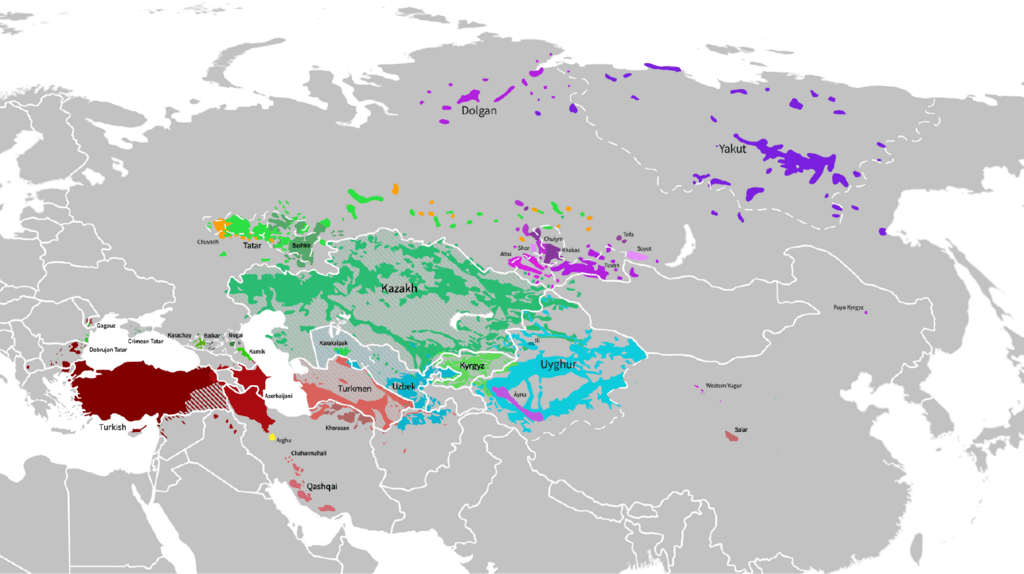

The Turkic people were another such group. Like many steppe tribes, their origins are very obscure, but they were caught up in this cultural soup, and over time grew and grew into more powerful tribal confederations. As they spread and intermixed with other steppe tribes, they also took on increasingly regional differences among each other.

Thus, the Turkish people of the Republic of Turkey (a.k.a. modern Türkiye) and the Uyghurs of north-western China have common ancestry. Some of their ancestors migrated west and contended with the Eastern Romans (a.k.a. the Byzantines), while others fought with the Chinese Tang dynasty onward. Yet in some distant, remote past they began as just one steppe tribe out of countless others and over time grew into a family of ethnicities and languages that spread all over Asia.

In Xuan-zang’s time, the Turkic tribes had formed a powerful confederation on the Eurasian steppe called the Western Turkic Khaganate. They called themselves the On oq budun (𐰆𐰣:𐰸:𐰉𐰆𐰑𐰣) or “People of the Ten Arrows” implying they were a federation of tribes, ruled by a single Qaghan (alternatively spelled Khaghan). These “Göktürks“, and their empire, remnants of an even larger Turkic Khaganate, were spread out far enough to have contact with China, the Sassanian Persians and Eastern Romans all at once.

Great Tang (e.g. Tang Dynasty China) would come to rule this entire area at the zenith of its power in the decades ahead, and the Khaganate reduced to a puppet state, but in Xuan-zang’s time, it was still a land ruled by Turkic people.

Meeting the Khagan

As Xuan-zang and his party descended the Tian-Shan mountains they came near to the modern city of Tokmok in Kyrgyzstan. More precisely, Xuan-Zang came the ancient capital of Suyab, also called Ak-Beshim, just to the southwest. This region was fed by the Chu river and was a verdant land compared to the desert wastes elsewhere. The Khaganate used these lands as a resting place when not on the march.

The leader of the Khaganate, Tong Yabghu Qaghan (Tǒng Yèhù Kěhán, 统叶护可汗 to the Chinese) was eager to meet Xuan-zang and provided a fitting welcome. Xuan-zang, for his part, gave the Qaghan a letter of introduction from the king of Turpan.

Xuan-zang described the Qaghan thus:

[the Qaghan] was covered with a robe of green satin, and his hair was loose, only it was bound round with a silken band some ten feet in length, which was twisted round his head and fell down behind. He was surrounded by about 200 officers, who were all clothed in brocade stuff, with hair braided. On the right and left he was attended by independent troops all clothed in furs and fine spun hair garments; they carried lances and bows and standards, and were mounted on camels and horses. The eye could not estimate their numbers.

The Silk Road Journey with Xuan-zang, page 32

Tong Yabghu Qaghan’s “palace” was a great yurt, wherein a feast was held. The guests enjoyed such foods as wine, mutton, and boiled veal among other things. Since Xuan-zang was a Buddhist monk, he was forbidden to eat meat and drink alcohol, and thus he was served delights such as rice cakes, cream, mare’s milk, sugar, and honey instead.

Once everyone was settled down, Tong Yabghu Qaghan asked poor Xuan-zang to make a Buddhist sermon on the spot.

Xuan-zang had to be careful not to ruin the mood of the occasion, so he opted for a sermon on the need for goodwill (metta in Buddhism) towards all beings, and on the benefits of the religious life. The Qaghan was evidentially impressed. In fact, this wasn’t the Qaghan’s first encounter with a Buddhist monk. Apparently, some years earlier a Buddhist monk from India named Pabhakarmitras had journeyed through these lands on the way to China, and so the Qaghan was well-disposed to the religion. He even tried to convince Xuan-zang to stay among his people, but Xuan-zang declined. Unlike the king of Turpan, the Qaghan seemginly took no offense and offered to send a ethnically Chinese soldier to accompany Xuan-zang for part of the way.

More importantly, the Qaghan gave Xuan-zang both gifts and letters of introduction to share with the petty princes along the way, who were all vassals of the Qaghan.

Finally, it was time to leave.

To Fabled Samarkand

From the great yurt camp at Sayub, Xuan-zang was escorted by the Qaghan part of the way, but they eventually parted. After leaving the Chuy region, the land reverted back to desert, namely the Kyzylkum Desert, also known as the Desert of Red Sands. Xuan-zang’s party journey to the next city, the city of Tashkent (modern Uzbekistan) named Zhěshí (赭時) in Chinese at the time, proved difficult, but they did eventually reach it after crossing the Jaxartes River. Of the crossing, Xuan-zang describes the scenery.

North-west from this [river crossing] we enter on a great sandy desert, where there is neither water nor grass. The road is lost in the waste, which appears boundless, and only by looking in the direction of some great mountain, and following the guidance of the bones which lie scattered aboout, can we know the way in which we ought to go.”

The Silk Road Journey with Xuan-zang, page 34

Xuan-zang does not seem to spend much time in Tashkent (I wasn’t able to find much description of his time in my limited resources), and continued on in a more Westerly direction towards Samarkand.

Fun fact, after crossing the Jaxartes river and passing Tashkent, Xuan-zang and his party entered into lands once ruled by the Bactrian Greeks. To the south and west of Tashkent was the former outpost city of Alexandria Eschate, which had been the most northerly city of the Greeks. It was a strong fortress city under king Euthydemus I, but suffered constantly attacks by the native Iranian Sogdian peoples. By the 1st century AD, the city had reverted back to local control, and the Greeks retreated from the area. By Xuan-Zang’s time this was all a distant memory.

We’ll cover Samarkand in the next episode, because things take a dangerous turn in this output of the Sassanian Persians, and also from here, the road will turn back south toward India at last.

You must be logged in to post a comment.