Way back in high school, like most American kids, I had to study things like Spanish, French, etc. I took German for two years in high school, but I didn’t find it very interesting, and I didn’t like my teacher very much. So, I never put in much effort. Later, one of my friends told me that we offered Mandarin Chinese at my high school, and I was just beginning my “teenage weeb phase”, so I was definitely curious.1

Our teacher, Mrs. Wu, was a very nice elderly teacher, even though she was in over her head dealing with a bunch of teenagers. Still, exploring something exotic like Chinese language really interested 16-year old me, and I was a pretty motivated student. I tried to learn both Traditional Chinese characters (used in Taiwan) and Simplified characters (Chinese mainland). My best friend at the time was Taiwanese-American, and I used to practice with his immigrant parents.

Anyhow, long story short, once I got into college, I focused on other priorities, and gradually, I forgot my Chinese studies.

Lately, I have been dabbling in Duolingo and learning Chinese again. I forget why, but I guess it’s partly fueled by nostalgia, but also because I already know how to read many Chinese characters through my studies of Japanese.

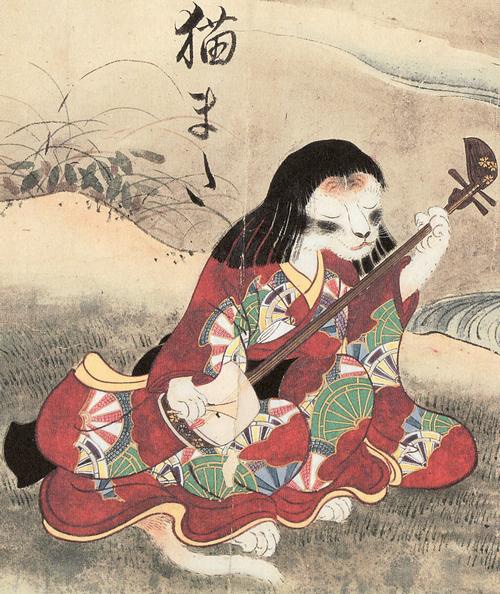

It’s been fascinating to see how Japanese kanji (Japanese-imported Chinese characters), and modern Chinese characters overlap and yet differ. The important thing to bear in mind is that Japan (like other neighboring countries), imported Chinese characters at an earlier stage in history, and over centuries the usage, pronuncaition and such have all diverged.

Take this easy sentence in Chinese:

All of these Chinese characters are used in Japanese, and without any prompts, I can read this and get the gist of what its saying, but there’s some notable divergences.

These Chinese sentence above is:

日本菜和中国菜

rì běn caì hé zhōng guó caì

A Japanese equivalent might be:

日本料理と中国料理

nihon ryōri to chūgoku ryōri

A few interesting things to note.

- The character 菜 is used in modern Chinese to mean food in general, but in Japanese it means vegetables. So the usage has diverged. I noticed that Chinese

- The country names, 中国 and 日本 are used by both languages, but the pronunciation has also diverged considerably. 中国 is pronounced zhōng guó in Chinese, and chūgoku in Japanese. You can kind of hear the similarities, but also the pronunciation has diverged for centuries.

- The character 和 (hé) is used in Chinese to mean “and”, but in Japanese a system of particles is used instead. Interestingly, 和 is used in Japanese, for example the old name of Japan was Yamato (大和) or modern words like heiwa (平和, “peace”). The pronunciation is wa, so it has diverged as well.

On thing I haven’t really delved into is the native Japanese readings for Chinese characters. Chinese characters are a foreign, imported writing system to Japan, so native words sound completely different even when written with Chinese characters. The word for 中国 (chūgoku) derives from Chinese, but 中 by itself is pronounced as naka (“middle”) which is a native Japanese word (not imported).

Anyhow, this is just a quick overview of how two entirely different languages both adopted the same writing system, but have diverged over time. If you add in languages like Vietnamese and Korean that also adopted Chinese characters, the picture is even more fascinating.

P.S. Through Duolingo, I learned that the Chinese word for hamburger is hàn-bǎo-bāo.

Chinese has to import foreign words using Chinese characters that at least kind of sound like the original. Japanese uses a second syllabary system, katakana, to approximate the same thing, although in the past Chinese characters were used as well. Hence, America is usually written as amerika アメリカ, but in more formal settings it is called beikoku 米国 (compare the pronunciation with Chinese měi guó).

1 The fact that my high school even offered Chinese language at that time (1990’s America) is pretty unusual, but I am grateful for the option. Also, thank you Mrs Wu if you ever happen to read this.

You must be logged in to post a comment.