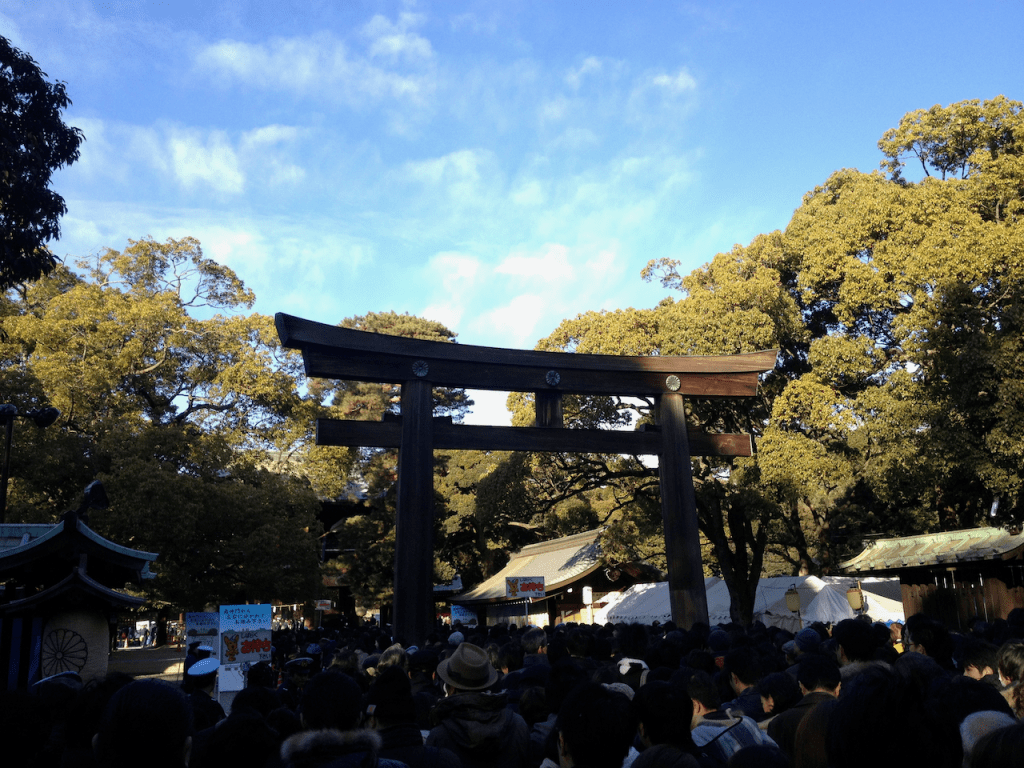

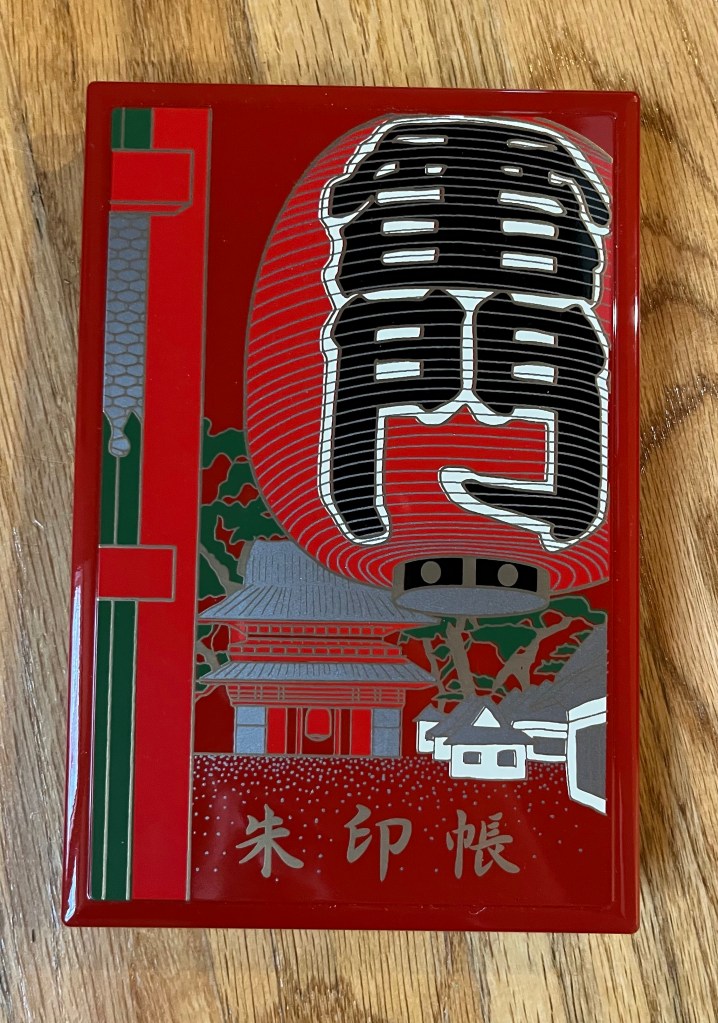

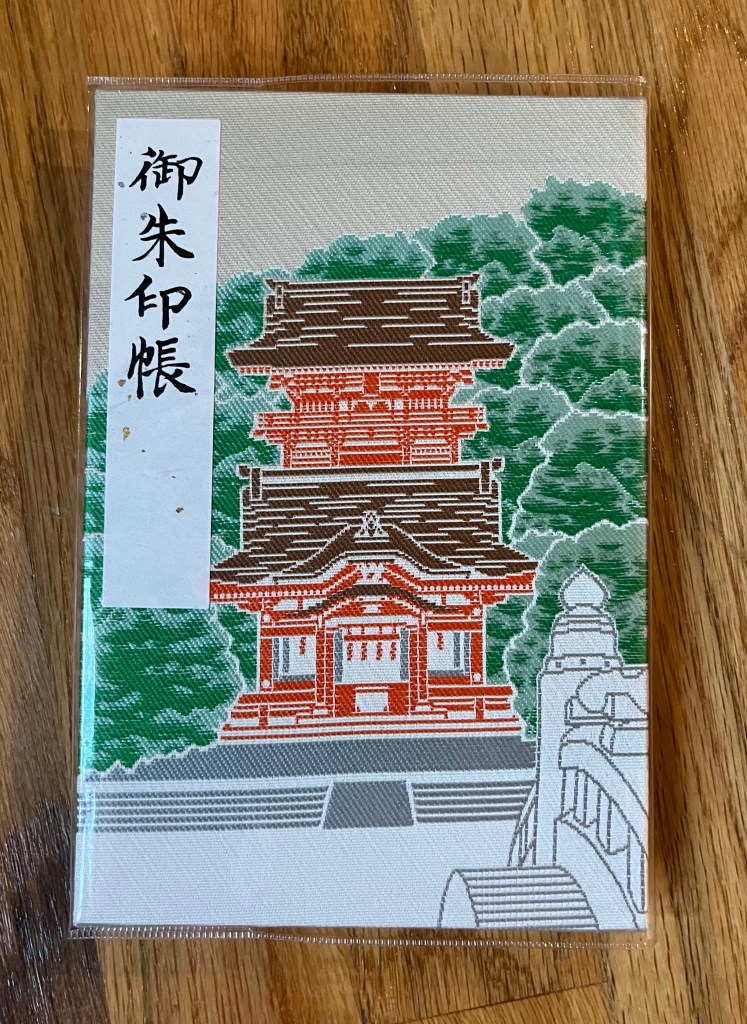

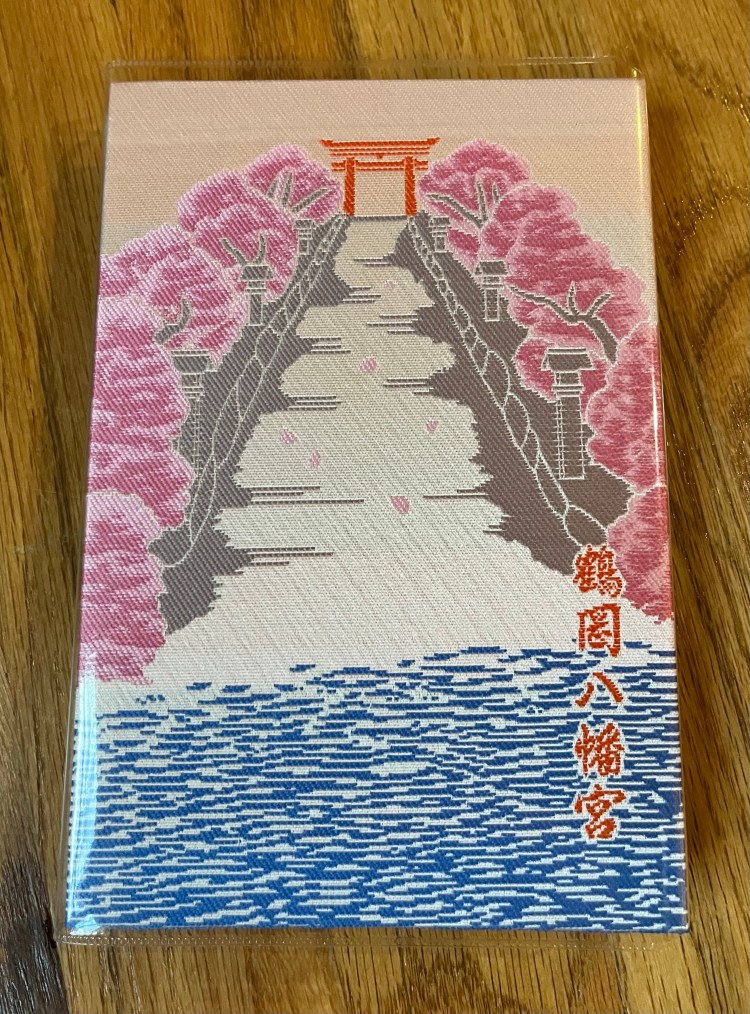

In our recent visit to Kyoto, the ancient capitol of Japan, we also took a day to visit the city of Nara, which is an even earlier capitol. Downtown Nara has several highlights but two of them are the Buddhist temple of Kofukuji, and the Shinto shrine of Kasuga-Taisha (“Kasuga Grand Shrine”). Kofuku-ji Temple is one of the central temples of the once powerful Hosso sect, and Kasuga Grand Shrine is a famous shrine within Shinto religion,1 and hosts a primeval forest that has been untouched since antiquity. I might post more photos of each later.

What makes these two sites important is that they were both tied to the powerful Fujiwara Clan.

During the Nara Period of Japanese history, the Fujiwara were just one of several noble houses that supported the Imperial family. Back then they were called the Nakatomi (中臣) Clan. During a power-struggle between the Imperial family and the Soga clan, one Nakatomi no Kamatari (614 – 669) came to their rescue and helped defeat the Soga. Thereafter, the Imperial family relied on Kamatari to help reform and strengthen the government. The Nakatomi earned the clan name Fujiwara later under Emperor Tenji. So far so good.

However, starting with Kamatari’s son, Fujiwara no Fuhito (who also helped compile the Nihon Shoki), the clan gradually began to monopolize key positions, increasingly through inter-marriage with the Imperial family. By the 12th century, every member of the Imperial family married members of the Fujiwara clan, over and over, generation after generation. This allowed the head of the Fujiwara to assume the role of “regent” (sesshō, 摂政) to his offspring who were children on the Imperial throne, when switch to “chief advisor” (kanpaku, 関白) when they were old enough to rule on their own. That same advisor could also force the Emperor to abdicate to their son (whose mother was also from the Fujiwara clan) when necessary, allowing the same official to be regent to their grandson.

Further, by holding key government positions, the Fujiwara could also manipulate property laws on their private holdings in the provinces, increasing personal revenue. The Fujiwara were not the only noble houses to do this, even the Imperial family did it, but through their connections and influence, they profited immensely from the untaxed revenue of their lands.

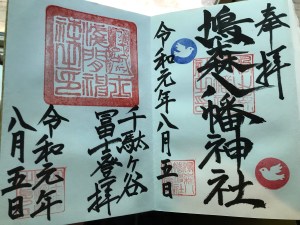

With this increasing power and wealth, the Fujiwara sponsored a number of building projects. One of these was Kofukuji Temple, which was sponsored by the Fujiwara as far back as 669, but with its increasing connections to the Fujiwara, the building complex greatly increased in size and wealth.

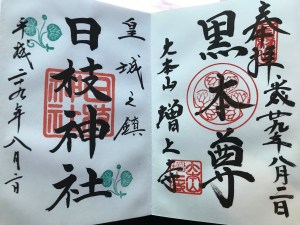

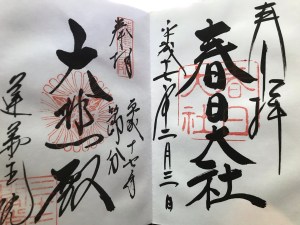

Further, the family Shinto shrine of Kasuga Taisha prospered:

But the price of all this interconnectedness between the Fujiwara and religious establishments came at a cost. The religious institutions became extensions of Fujiwara power, with clan members given key positions locking other people out,2 and fielding armies of warrior monks against other rival temples.

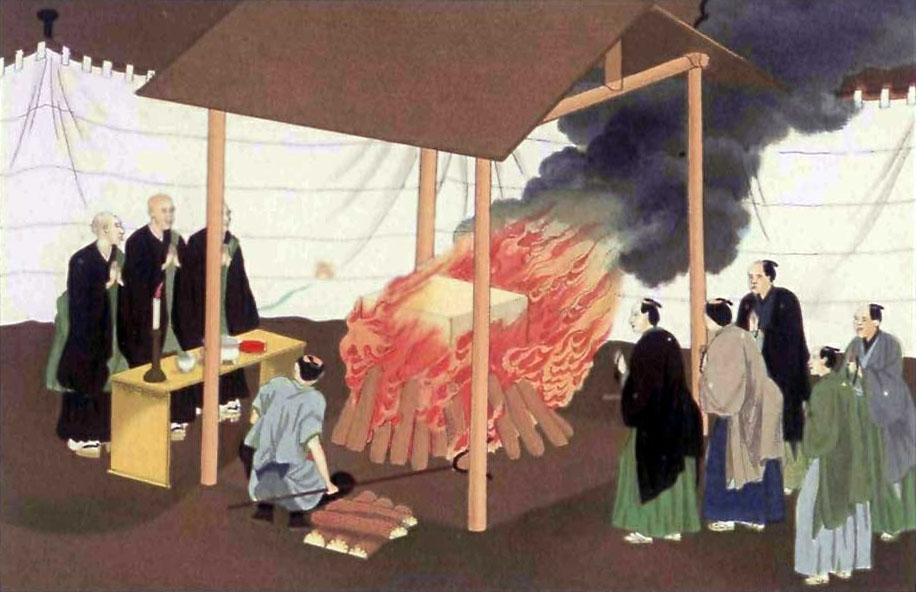

By the time the system collapsed, the Fujiwara’s power began to diminish. Kofukuji Temple was largely burned down,3 and the original clan had become so large that it gradually broke up into five different clans, each one marrying with the Imperial family as needed:

| Japanese | Romanization | Founded |

| 近衛 | Konoe | 12th century |

| 鷹司 | Takatsukasa | 1252 |

| 九条 | Kujō | 1191 |

| 一条 | Ichijō | 13th century |

| 二条 | Nijō | 1242 |

Some of these new clans, especially the Kujō, even assumed positions of power with the new Kamakura shogunal family after the untimely death of Sanetomo, the 3rd shogun. Further, by the 19th century, with Westernization of Japan (e.g. the Meiji Period) the Five Regent Houses all became merged into the Western-style “peerage“, but by 1945, now hundreds of years since their founding, the five regent clans were finally abolished for good with the post-World War II reforms of the Imperial system.

In any case, after the 12th century, the centers of power had since moved. Kofukuji Temple, having been burned down in various conflicts, never quite rebuilt its power. Newer forms of Buddhism had taken root, and new centers of religious devotion had arisen. Kasuga Taisha grand shrine, being located in Nara, was now remote as the capitol had moved further and further east. When I visited Kofukuji Temple in 2010, and again this year (2023), some things had changed. The central Golden Hall (中金堂, Chū-kondō), had finished reconstruction for the first time in centuries. But even now, many of the original buildings have not been reconstructed.

Throughout Japanese history, the Fujiwara clan maintained prestige for centuries, but actual power continued to slip from their grasp bit by bit after the 12th century, and these historical relics in Nara are shadow of their former selves, and of Fujiwara power.

1 People are often surprised to learn that Japan has essentially two religions: Buddhism which came from India (via China), and Shinto which is the native religion. The two have been pretty intertwined culturally for centuries. It’s a long story.

2 Some of those who were excluded went on to found other Buddhist sects later partly out of disillusionment with the establishment.

3 Quite a few temples burned down in times of war, not just Kofukuji. Todaiji also burned down many times, as well as Enryakuji on Mt Hiei, among others.

You must be logged in to post a comment.