During our most recent trip to Japan, I picked up some nice incense from Zojoji Temple, and my wife separately picked up some from Sanjusangendō Temple in Kyoto.1 We also bought some incense last year at the Golden Pavilion and Ryoanji. It’s a thing in our house. We actually use incense a fair amount: I use it for Buddhist home services, my wife uses it to honor her deceased mother. Sometimes we also just light it for guests who come over.

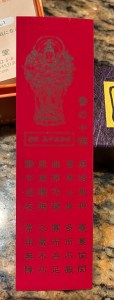

When we opened the incense box from Sanjusangendō, we were surprised to see this little red slip of paper. This is not bad photography: the paper is hard to read. At the top is a Buddhist image,2 but below that is something written on the slip of paper called the Ten Virtues of Incense, or kō no jittoku (香の十得). The Ten Virtues is a form of Chinese-style poetic verse, or kanshi (漢詩) originally composed by the 15th century eccentric Rinzai-Zen monk Ikkyu.

The Ten Virtues are ten aspects of incense that Ikkyu felt was beneficial for whomever uses it. Nippon Kodo has a really nice English-language page about it, including a translation. Feel free to stop and take a look. I’ll wait.

To summarize the benefits here (refer to other sources for proper translations), the ten virtues are:

- Spiritual awakening

- Purification of body and mind

- Removes impurity

- Brings alertness

- Brings comfort in solitude

- Brings moment of peace

- One doesn’t get tired of it

- Even a little is enough

- Stays fresh even in age.3

- You can use it every day.

Of course, it’s also important to use incense in a well-ventilated room. The smoke, while very pleasant, is probably not good for your lungs. I always open windows and doors before using it. Also, good quality incense tends to be less smoky. You can even find “reduce smoke” incense sometimes, which is probably healthier, though I would still keep good airflow just in case.

In any case, incense is pretty neat, and if you ever visit a Buddhist temple in Japan, you’re almost sure to find some really good quality stuff. But even if you can’t afford to travel, it’s not hard to find stuff online or in your area too.

Good luck and happy …….. inhaling?

1 We have visited this place a number of times over the years, including our “honeymoon” trip to meet the extended family in Japan way back when. And yet, I haven’t talked about it much. I actually really like this temple, but because they don’t allow much photography it’s hard to make a blog post about it. I might try one of these days, just haven’t figured out how to describe Sanjusangen-do without photos I can use.

2 The Buddhist image is the bodhisattva Kannon, in the form of 1000 arms, also known as senju kannon (千手観音). Since the temple venerates Kannon, this makes sense.

3 Speaking of our honeymoon trip way long ago, we went to a spa-resort place in Japan, and got these nice little incense envelopes. I put my envelope between two pages of a book at the time, shelved it, and forgot about it for years. I opened years later, and the oils of the incense had seeped through and stained the page, but it also left a really nice scent that still lasts. Even now 20 years later, the book still has a nice fragrance.

You must be logged in to post a comment.