As my studies of Ukrainian continues, one pattern that definitely appears over and over is the clear presence of grammatical gender. I’ve touched on this a bit in a recent post on how it relates to classical languages, but wanted to provide more context here.

The concept of grammatical gender is something that’s endemic to Indo-European languages (as far as I know),1 and is not related to the actual gender of a word. In Latin, the word miles means solider and is masculine (makes sense), but the Roman legion, legiō, had a feminine grammatical gender.

Modern western European languages such as Spanish and French tend to have shed and streamlined some aspects of grammatical gender. Neuter words no longer exist, so there’s only masculine and feminine genders left. Languages like English barely have any grammatical gender at all, even though it still exists in German to some degree.

Ukrainian language keeps the three classic genders: masculine, feminine and neuter, and like Spanish, French and Latin, nouns and adjectives have to agree with case (nominative, genitive, etc), number (singular and plural) and gender.

Here are three words:

| Ukrainian (Romanization) | Meaning | Gender |

| Кіт (kit) | A male cat | Masculine |

| машина (mashyna) | A car | Feminine |

| місто (misto) | A city | Neuter |

As far as I can tell, there is no definitely article like “the” or “a” in Ukrainian, but let’s use the word for “my/mine” in front of these and you can see how grammatical gender:

| Ukrainian (Romanization) | Meaning |

| Мий кіт (miy kit) | My cat |

| Моя машина (moya mashyna) | My car |

| Моє місто (moye misto) | My city |

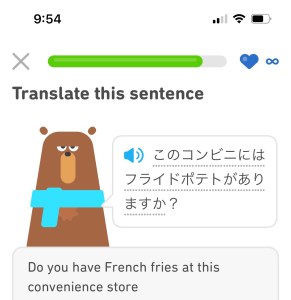

You can see how in all three cases the same word, “my”, changes according to grammar, and it’s not a small change. In the screenshot above from my Duolingo session, you can see that the adjective “older” changes the same way depending on whether it’s a sister (feminine) or brother (masculine).

Further, I was surprised that there are many words for living beings that are also divided by gender. For example кіт above means “cat”, but implies a male cat. The word for a female cat is кішка (kishka). For “friend” there are separate words for a male friend (друг, “druh”) and a female friend (подруга, “podruha”). Note that these are platonic friends, not boyfriend and girlfriend. There are separate words for those.

Also, from what I can tell, the plural friend has only one gender: друзі (druzi) means “friends” for example, though I am pretty fuzzy so far.

So far, I think I have only learned the nominative case (e.g. nouns as the subjects of sentences), so I suspect that these forms will also change depending on what part of the sentence a word is. This makes conjugation pretty tricky (just like Latin and Greek), but also means that you can upfront glean many details quickly once you get familiar with it.

Another example is in describing people. Ukrainian frequently identifies gender in a person through endings such as ець (ets) for masculine and ка (ka) for feminine. Thus, українець means a Ukrainian person, masculine, while українка means a Ukrainian person, feminine. Even words like “vegetarian person” have different endings: вегетаріанець (vegetarian, masculine) versus вегетаріанка (feminine).

P.S. I had my first actual conversation in Ukrainian recently, and I did a pretty lousy job. My mind blanked on words, and I mispronounced things. It’s been a long while since I learned a new language, and it’s easy to forget how little you actually know at first. But it also is a reminder to focus on fundamentals and nail those down before getting too hung up on the finer details. Easier said than done, but it’s been an interesting journey so far.

1 I have practically never seen any examples of it in languages like Japanese, Korean or Chinese or Vietnamese. Of course, there are gender-specific words, but inflections based on grammatical gender definitely do not exist. Bear in mind that the above Asian languages are in separate language families (despite being geographically next to one another).

You must be logged in to post a comment.