(Dear readers, I wanted to try and summarize the Pure Land Buddhist teachings in Ukrainian. There isn’t much information, so I wrote this post for Ukrainian audiences. It summarizes teachings from other posts. Thank you for your patience)

Привіт, я радий мати українських читачів, які цікавляться буддизмом. Тому я хотів написати цей блог саме для українців. Зверніть увагу, я трохи вивчив українську, але точно недостатньо, щоб писати блог. Тому мені доводиться часто користуватися Google Translate. Вибачте за будь-які помилки. Насолоджуйтесь цим постом і слава Україні

Буддизм Чистої Землі є вірною традицією в буддизмі. Багато людей в Азії та світі дотримуються буддизму Чистої Землі. Це просто, легко зрозуміти та легко застосувати на практиці. Для цього не потрібен ні гуру, ні храм. Ви можете почати як зараз.

За словами Будди Шак’ямуні, життя подібне до річки. На цьому березі розбрат, розчарування, невігластво, страх і так далі. На іншому березі — мир, доброзичливість і задоволення. Таким чином, буддизм вчить, як перепливти цю річку на інший берег.

Крім того, Будда Шак’ямуні навчив багатьох методів і «інструментів», щоб перетнути річку. Різні люди вважають за краще використовувати різні інструменти, але всі вони будують плоти, щоб переплисти річку. Буддизм чистої землі є одним із інструментів.

Буддизм Чистої Землі вшановує Будду Аміду (あみだ, 阿弥陀), Будду нескінченного світла.

Примітка: Про буддизм Чистої Землі я дізнався через японську секту «Джодо Шу» (じょうどしゅう, 浄土宗). Отже, я використовую японсько-буддійські терміни. Інші буддистські країни використовують інші терміни, але основне вчення те саме.

Аміда Будда — легендарний, або космічний, Будда, який обіцяє допомогти всім істотам дістатися іншого берега. Аміда Будда кличе людей зі своєї Чистої Землі, яка є притулком. Цей притулок доступний для всіх людей, ким би вони не були, якщо вони просто продекламують Нембуцу (ねんぶつ, 念佛).

Що таке нембуцу?

Нембуцу означає такі речі, як «думати про Будду» або «прославляти Будду» тощо. Зазвичай люди декламують нембуцу усно.

Японською мовою це вимовляється як наму аміда буцу (なむあみだぶつ, 南無阿弥陀仏).

У буддизмі існує священний текст під назвою Сутра безмежного життя, також відомий як Велика сутра Сухаватівюха. Ця сутра представляє Аміду Будду та його походження.

Давним-давно Аміда Будда був королем, який зустрів іншого Будду. Вчення Будди справило на нього таке враження, що він зрікся престолу і став буддійським ченцем. Він поклявся допомагати всім живим істотам, створивши безпечну гавань під назвою Сукхаваті («Остання радість»), а також став Буддою.

Цих обітниць насправді було 48 обітниць. 18-й обітниця є найважливішою. Це простий переклад:

Коли я стану Буддою, розумні істоти в усіх напрямках, які хочуть народитися в моїй Чистій Землі, повинні просто сказати моє ім’я принаймні 10 разів, і вони там народяться. Якщо це неправда, нехай я не стану Буддою.

Таким чином, якщо світ надто складний або людина не може слідувати традиційним буддійським шляхом, можна вибрати переродження в Чистій землі, промовляючи Нембуцу (наму аміда буцу). Це особистий вибір.

Засновник секти «Джодо Шу» Хонен (法然, 1133 – 1212) описав співчуття Аміди Будди як місячне світло. Він сяє скрізь, але лише деякі дивляться вгору:

| Японською | Коваленко | Переклад |

|---|---|---|

| 月かげの | цукі kaґе но | Немає такого села, |

| いたらぬ里は | ітарану сато ва | де б не світило |

| なけれども | накередомо | місячне світло, |

| 眺むる人の | наґамуру хіто но | але воно живе в серцях тих, |

| 心にぞすむ | кокоро ні дзосуму | хто його бачить. |

Так само в Сутрі безмежного життя є така цитата:

Якщо розумні істоти стикаються зі світлом Аміди Будди, їх три скверни усуваються; вони відчувають ніжність, радість і насолоду; і виникають добрі думки.

Але чим буддизм чистої землі відрізняється від християнства?

Фундаментальне вчення все ще є буддійським: живі істоти повинні «перепливти річку», щоб досягти короткого просвітлення. Аміда Будда просто допомагає на цьому шляху.

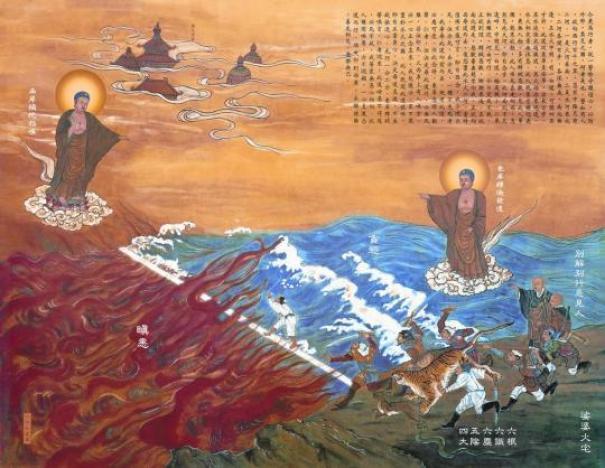

У VII столітті в Китаї жив чернець на ім’я Шандао (善導, 613–681). Він написав відому притчу під назвою «Притча про дві річки та білий міст». Ви можете побачити приклад ілюстрації нижче:

Підсумовуючи, притча вчить, що на цьому березі Будда Шак’ямуні вказує на міст. На іншому березі річки Аміда Будда кличе нас перепливти. Шлях вузький, але якщо ви прислухаєтесь до слів Будди Шак’ямуні та заклику Будди Аміди, ви пройдете безпечно.

Це базовий вступ до буддизму Чистої Землі, особливо до секти Джодо Шу. Якщо ви цікавитеся буддизмом, але відчуваєте розгубленість або самотність, просто спробуйте продекламувати Нембуцу. В якості основи використовуйте нембуцу.

У секті Джодо Шу існує традиція декламації нембуцу під назвою цзюнен (じゅうねん, 十念, «десять декламацій»). Звучить так:

наму аміда бу

наму аміда бу

наму аміда бу

наму аміда бу

наму аміда бу

наму аміда бу

наму аміда бу

наму аміда бу

наму аміда буцу

наму аміда бу

Дев’ята декламація має додаткове “цу” в кінці. Крім того, люди зводять руки разом у молитві, коли вимовляють нембуцу. Це називається «гасшо».

Ви можете побачити приклад тут, у храмі Зодзідзі в Токіо, Японія:

Вибачте, що мені довелося скористатися Google Translate, але я сподіваюся, що ви знайшли щось корисне, і я сподіваюся, що побачите світло Аміди Будди.

наму аміда буцу

You must be logged in to post a comment.