Recently, I’ve been delving into both the Sanskrit and Pali languages, both used for Buddhist religious scripture, and just when I thought I had things figured out, I realize the situation is even more complicated and fascinating than I thought.

Sanskrit is a language that was brought to India by invaders who called themselves the Arya (“the noble”), but had origins in what is now Iran. They came to India sometime after 2000 BCE and settled across northern India and surrounding areas, subjugating the native population, and bringing their religious values with them. From there, we see very early religious inscriptions such as the Rig Veda, composed in very old Sanskrit (e.g. “Vedic Sanskrit”).

But, gradually, Sanskrit and what was spoken informally “on the ground”, diverged. This diverged by regional variances, social classes, etc. They could probably understand each other’s regional dialects the same way that Americans can understand Australian English, and Australians understand American English, or Scottish English, etc, and all of them differ from “textbook English” also known as Standard English.

One might also draw an example from Latin. Classical Latin, such as the writings of Cicero, differed from “vulgar Latin” such as that spoken in the provinces. Further, vulgar Latin as spoken by the Celts in Gaul probably differed from vulgar Latin spoken by Berbers in north Africa or Egypt. Even Cicero’s spoken Latin probably differed than his writings.

Such regional dialects or variances of the original Sanskrit included:

- Magadhi – A language spoken in the kingdom of Magadha, and quite likely the Buddha’s native language. It is spoken today in India as well, but like Ancient Greek has changed over time to its modern version.

- Kosalan – A language spoken in the neighboring kingdom of Kosala, also mentioned in early Buddhist texts.

- Arda-Magadhi – “Half-Magadhi”, a possible predecessor to Magadhi above, or at least closely related.

- Paishachi – A popular, possibly literary-only language, though more research is needed.

- Maharashtri – A language spoken more to the southwest of India and frequently used in poetry. Modern day Marathi and Konkani derive from it.

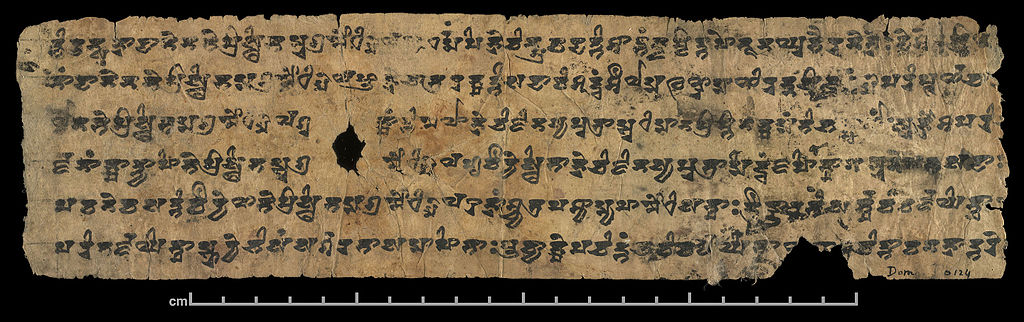

- Gandhari – A prakrit spoken in north-west India, in the important region of Gandhara, and used in some Buddhist scriptures composed in the region, instead of Pāli. Examples of recoverd texts here.

Here’s an example I found on Wikipedia:

In Pali language (we’ll get to that shortly):

Yo sahassaṃ sahassena, saṅgāme mānuse jine;

Ekañca jeyyamattānaṃ, sa ve saṅgāmajuttamo.Greater in battle than the man who would conquer a thousand-thousand men, is he who would conquer just one — himself.

The Dhammapada verse 103

…compare with Ardhamagadhi:

Jo sahassam sahassanam, samgame dujjae jine.

Egam jinejja appanam, esa se paramo jao.One may conquer thousands and thousands of enemies in an invincible battle; but the supreme victory consists in conquest over one’s self.

Saman Suttam 125

Speaking of Pāli, what’s up with Pāli? The earliest Buddhist scriptures, or sutras, are recorded in Pāli language, but Pāli isn’t technically a Prakrit like those shown above. It seems to be a language that arose as a kind of lingua franca between Prakrits.1

It makes sense why early Buddhist sutras are recording in it then: rather than recording in each Prakrit for the benefit of local audiences, pick something that was generally understood, even if imperfectly.

Pāli may have arisen around the 3rd century BCE, two to three hundred years after the Buddha, so here’s a hypothetical (repeat: hypothetical) timeline:

- The Buddha preached in his native language, Magadhi (assuming that’s what he spoke), probably around the 5th or 6th century BCE. It’s also possible he used other Prakrits as well depending on his audience, assuming they were mutually intelligible.

- Disciples remembered his teachings, and per Buddhist tradition, recited them as beset as they could recollect after this death in the First Buddhist Council.

- Per existing Indian tradition, the teachings were then passed down for centuries from teacher to students.

- As Prakrits developed and diverged over time, it probably became harder to keep things consistent across Buddhist communities, and the communities relied on more. Since it was widely used anyway, this was probably a simple, practical move.

- As Buddhist tradition changed from oral to written history, Pāli was the logical choice for some Buddhist schools, such as the Theravada. Other Buddhist school at the time stuck to local Prakrits (some of which became part of the Mahayana canon later), such as in the Gandhara region.

- As Buddhism spread even further, and Pāli fell out of use in India, Sanskrit became the liturgical language of choice and Buddhist scriptures, notably in the Mahayana tradition were shoe-horned into Sanskrit in successive waves. Given the rise of Hindu religion, which relied on Sanskrit for scripture, Buddhist communities may have felt the need to “keep up”.

Anyhow, this is speculation, but seems to fit what I’ve learned so far, and shows a fascinating evolution where Sanskrit sets the foundation, but dialects flourish until a new lingua franca is needed (namely, Pāli), until things sort of come full-circle and return to Sanskrit again, at least for the Mahayana tradition.

However, a couple points should be emphasized:

- The Buddha probably didn’t preach in Pāli language. We may never know exactly what the language was, but it is likely a local prakrit, or more than one.

- Prakrit languages are neither Sanskrit nor Pāli, but possibly developed in this order (more research needed): Sanskrit at time of migration into India -> Prakrits -> Pāli -> Classical Sanskrit

Thanks for reading!

1 Speaking of “prakrit”, there is not a universally agreed upon standard as to which languages at the time are prakrits, and which ones aren’t. In some broader definitions, Pāli language is considered another prakrit. As an amateur, I have no opinion one way or another.

You must be logged in to post a comment.