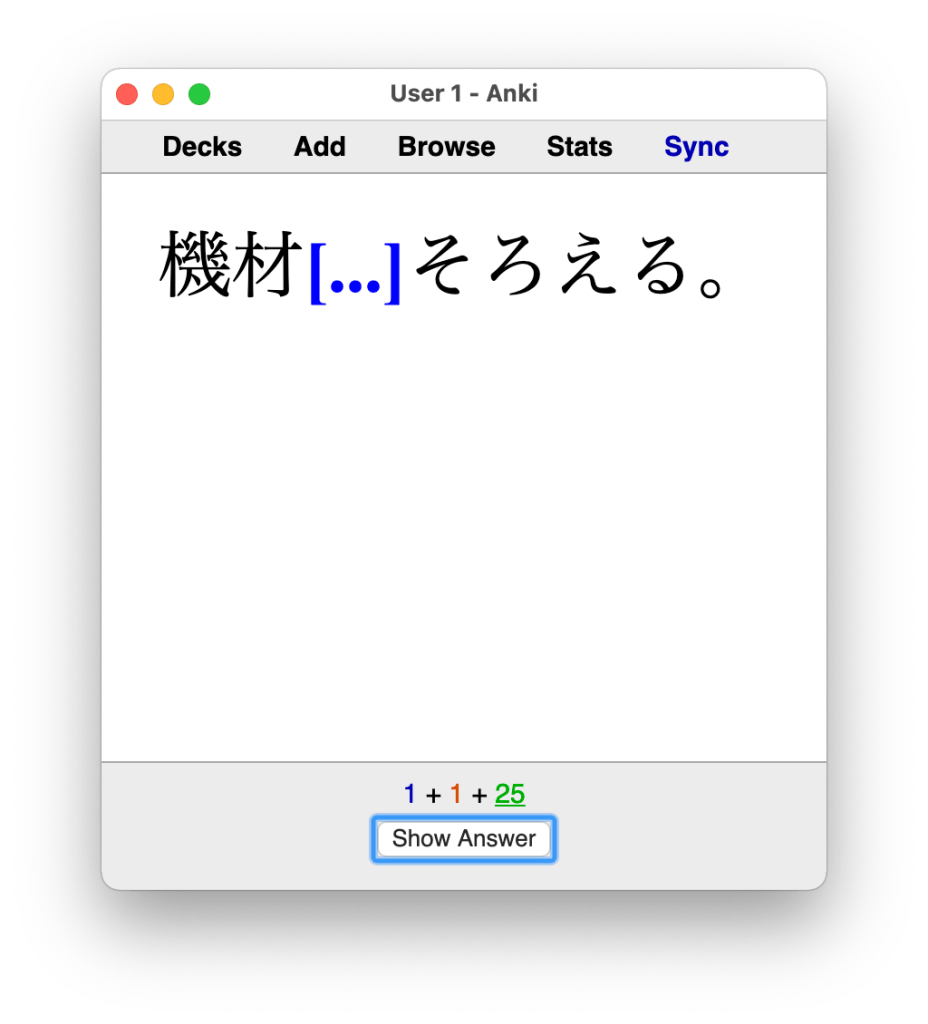

As I mentioned in my previous post, as I build up my vocabulary for the JLPT exam, N1 level, the number of flash cards I have in Anki has exploded. In the last two months, I have built up more than 1200 cards in my Anki collection through studying vocabulary guides and reading Japanese manga we have lying around at home.

Because Anki is a spaced-repetition service (or SRS), the more you guess a card correctly, the less it appears. That benefits you by allowing you to focus more on cards you struggle with. But when you learn a lot of new vocabulary in a short span of time, even with SRS, daily practice can be a nightmare because a large number of cards can come in “waves” all on the same day. And if you don’t review those cards, more will soon pile up.

When you open your SRS tool and have 120+ cards to review and 20 new ones, and you are a working parent, this gets pretty discouraging. Plus, I am only one-sixth of the way through my vocabulary guide so this amount will grow a lot more in the coming months.

To deal with this madness, I learned a feature in Anki that lets me limit the number of new cards and cards to review per day:

This feature has been very helpful for me because it gives me a reasonable limit to practice daily, even though it slows down my progress. The idea is to break up the study into smaller, discreet chunks of time. It also smooths out “waves” of flashcards overwhelming me when too many of them are all due on the same day.

The question then is how much is the right amount? I’ve play around with a few values so far: 4 new cards + 45 reviews, 6 new cards + 60 reviews, 3 new cards + 30 reviews, and so on. In my experience, I found that smaller is better, so I’ve settled on 3 new cards a day and 30 reviews. If I have a slow day and more free time, I can do the Custom Study feature to learn extra cards, but if I complete my 30 reviews that’s good enough.

The difference in the long-run is small, and it’s mostly psychological, but smoothing out your study into small daily efforts helps in the long-run, I believe.

You must be logged in to post a comment.