For months, I’ve had on my to-do list to go and fix up the Wikipedia article about the nembutsu (or nian-fo in Chinese). I had started contributing to that article way back in 2006 shortly after I first got interested in Pure Land Buddhism, and occasionally update or add details. The article was flagged for some quality control issues recently, and I decided to help clean it up.

As I began to write some updates to the article, though, and trying to distill what the nembutsu is within the Pure Land tradition, I realized that this is a really tough question. There’s centuries of interpretations, layers of culture, and divergent viewpoints. I tried to summarize this in an older article, but after reading over that article, I realized that I didn’t quite hit the mark there either.

So, let’s try this again.

Pure Land Buddhism is a large, broad, organic tradition within Mahayana Buddhism (an even bigger tradition). It is not centrally-organized, but follows many trends and traditions across many places and time periods. However, these traditions all have a couple things in common:

- Reverence toward the Buddha of Infinite Light (a.k.a. Amitabha Buddha, Amida, Emituofo, etc.). The nature of who or what Amitabha Buddha is is open to interpretation though.

- Aspiration to be reborn (as in one’s next life) in the Pure Land of Amitabha Buddha. There have been many ways to interpret what exactly this means, but I am sticking to the most simple, literal interpretation for now.

In any case, these two things are what make the “Cult of Amitabha” what it is. By “cult” I mean the more traditional, academic definition, not the modern, negative definition. Amitabha is to Mahayana Buddhism, what the Virgin Mary is to Catholicism.

Every Pure Land tradition across Buddhist history is mostly focused on #2: how to get to the Pure Land. The early Pure Land Sutras spend much time describing how great Amitabha Buddha is, and how getting to the Pure Land is so beneficial towards one’s practice, but differ somewhat on how get reborn there.

One early sutra, the Pratyutpanna Sutra is one of the first to mention Amitabha and the Pure Land at all, but it very strongly emphasizes a meditative approach, in order to achieve a kind of samadhi. According to Charles B Jones, being reborn in the Pure Land wasn’t even mentioned in this sutra, nor Amitabha’s origin story. It was a purely meditate text. Nonetheless, this sutra was highly favored by the early Chinese Pure Land Buddhists, namely the White Lotus Society started in the 5th century by Lushan Huiyuan.

The main textual source for being reborn in the Pure Land is from the Immeasurable Life Sutra, also called the Larger [Sukhavati Vyuha] Sutra. This is where we see the famous 48 vows of the Buddha, including the most important, the 18th vow (highlights added):

設我得佛。十方衆生至心信樂。欲生我國乃至十念。若不生者不取正覺。唯除五逆誹謗正法

(18) If, when I attain Buddhahood, sentient beings in the lands of the ten quarters who sincerely and joyfully entrust themselves to me, desire to be born in my land, and call my Name, even ten times, should not be born there, may I not attain perfect Enlightenment. Excluded, however, are those who commit the five gravest offences and abuse the right Dharma.

translation by Rev. Hisao Inagaki

This is where things get interesting, in my opinion.

The Chinese character 念 (niàn) was used to translate the Buddhist-Sanskrit term Buddhānusmṛti or “recollection of the Buddha”. But, according to Jones, the Chinese character 念 had multiple nuances in Chinese:

- To mentally focus on something.

- A moment in time.

- Reciting the Confucian Classics aloud.

And in fact each one of these interpretations can be applied to the nembutsu (Chinese niànfó) because it means niàn (念) of the Buddha (fó, 佛).

But which is it: concentration, a moment of recollection, or verbal recitation?

Most of the early Chinese Buddhist teachers like Tanluan, Daochuo and Shandao all promoted a mix: usually visualization was the superior method, but verbal recitation was a fallback for people who couldn’t dedicate themselves to visualization-meditation and ritual. The earliest Buddhist teachers mostly emphasized the visualization-meditation approach, but by Shandao’s time (7th century) the verbal recitation was deemed the most effective method.

Later, in Japan, the monk Genshin (not to be confused with the game…) summarizes these various methods in his 10th century work, the Ojoyoshu. It was a high quality work and even praised by Chinese monks when it was sent over as part of Japan’s diplomatic missions. But Genshin came to the same basic conclusion: the nembutsu can be any one of the three.

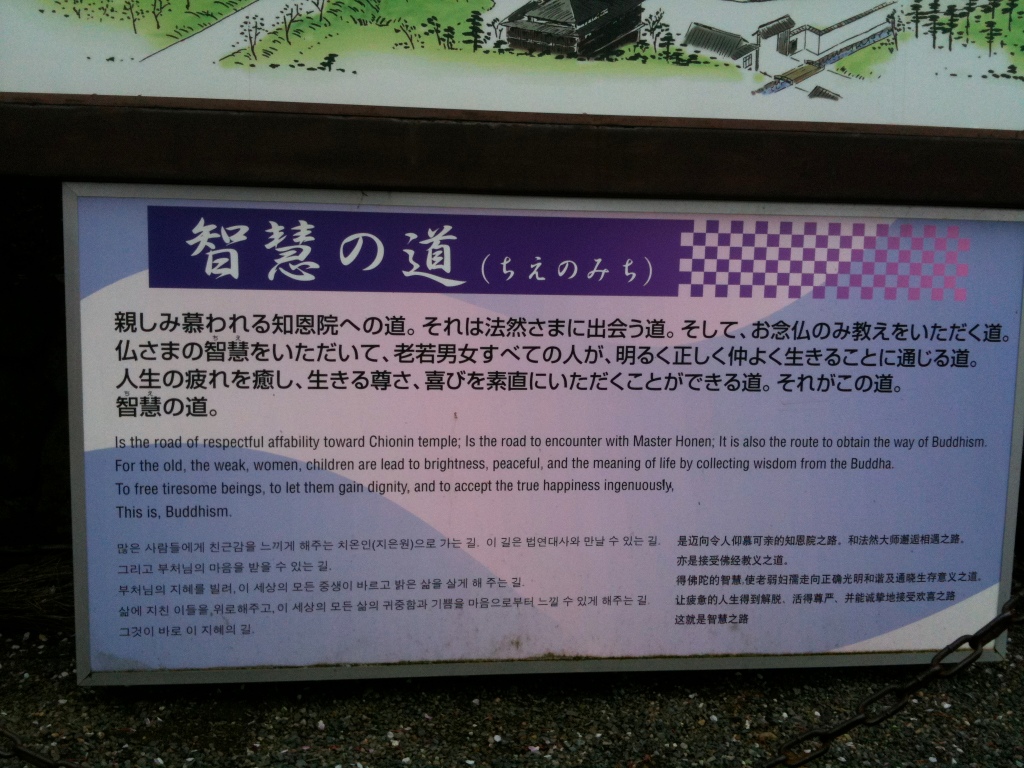

Finally we get to Buddhist teachers like Honen (12th century), who taught that the verbal recitation was the only viable choice. Honen praised past methods, but his target audience was a mostly illiterate population, as well as monks whose monastic institutions had largely declined into corruption and empty ritual. So, for such people, better to rely on Amitabha Buddha’s compassion and recite the verbal nembutsu wholeheartedly.

This approach isn’t that different from the Chinese approach which varied by teacher or patriarch but through Shandao’s influence had a parallel development. Some teachers emphasized the efficacy of simply reciting the nembutsu (much like Honen), others added the importance of concentration while reciting the nembutsu.

However, turning back to the Larger Sutra, let’s go back to the 48 vows. The 19th and 20th vows state:

(19) If, when I attain Buddhahood, sentient beings in the lands of the ten quarters, who awaken aspiration for Enlightenment, do various meritorious deeds and sincerely desire to be born in my land, should not, at their death, see me appear before them surrounded by a multitude of sages, may I not attain perfect Enlightenment.

(20) If, when I attain Buddhahood, sentient beings in the lands of the ten quarters who, having heard my Name, concentrate their thoughts on my land, plant roots of virtue, and sincerely transfer their merits towards my land with a desire to be born there, should not eventually fulfill their aspiration, may I not attain perfect Enlightenment.

So, taken together, the 18-20th vows cover the various interpretations of 念 we discussed above. All of them are included in Amitabha’s vows to bring across anyone who desires to be reborn there. The common theme is sincerity (至心 zhì xīn). If you look at the original Chinese text, all three include “sincerity”.

Further, when asked about how many times one should recite the nembutsu, Honen replied:1

“….believe that you can attain ojo [往生, rebirth in the Pure Land] by one repetition [of the nembutsu], and yet go on practicing it your whole life long.”

So, let’s get down to business: what is the nembutsu / niànfó ?

Based on the evidence above, I believe that the nembutsu is any of these Buddhist practices described above, taken under a sincere aspiration to be reborn in the Pure Land. It’s about bending one’s efforts and aspirations toward the Pure Land.

If you are calculating how to be reborn, or if your heart’s not 100% into it, then it may be a waste of effort.

Instead, if you feel unsure, study the Buddhist doctrines, get to know the Pure Land sutras, read about past teachers and if you feel fired up about, recite the nembutsu, or do whatever moves you. You will just know when. The more you put into it, the more you get out of it too.

Amitabha’s light shines upon all beings, like moonlight, and if you feel inspired by it, just know that you’re already halfway to the Pure Land.

Namu Amida Butsu

1 The site is long gone, sadly, but the Wayback Machine has an archive of the site. The updated Japanese-only site is here.

You must be logged in to post a comment.