Imagine if you will a kids martial arts school. The kids (including my son) are on the floor practicing, while the parents are sitting and watching. A pair of moms gossip, while bored dads check their phones constantly.

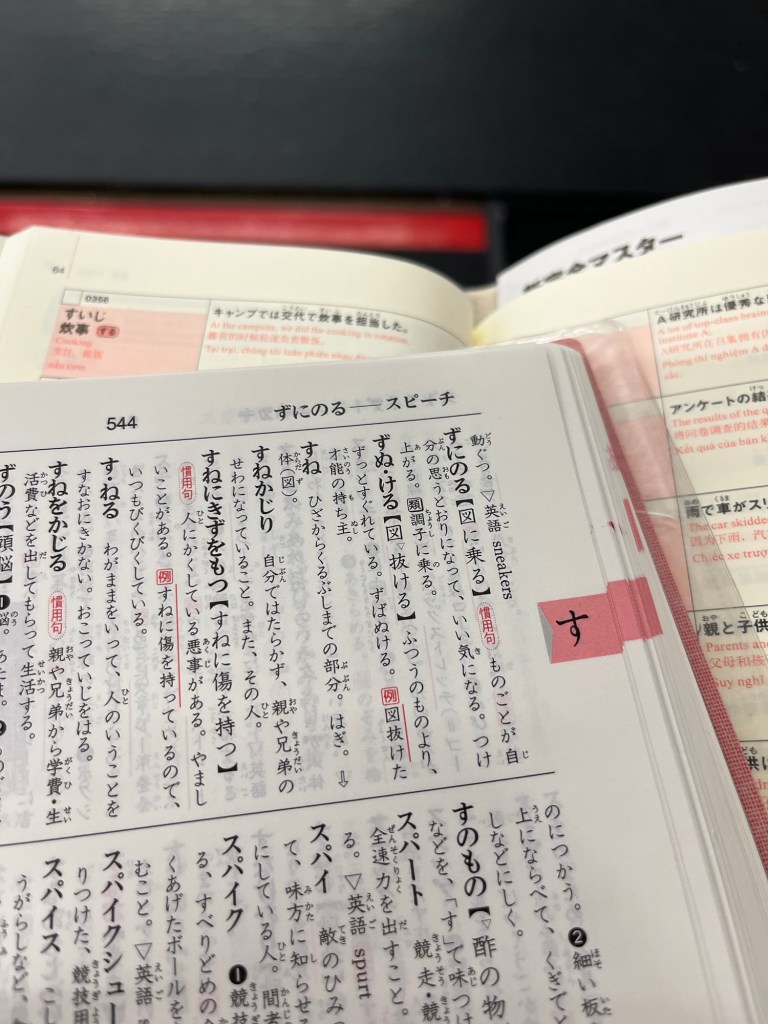

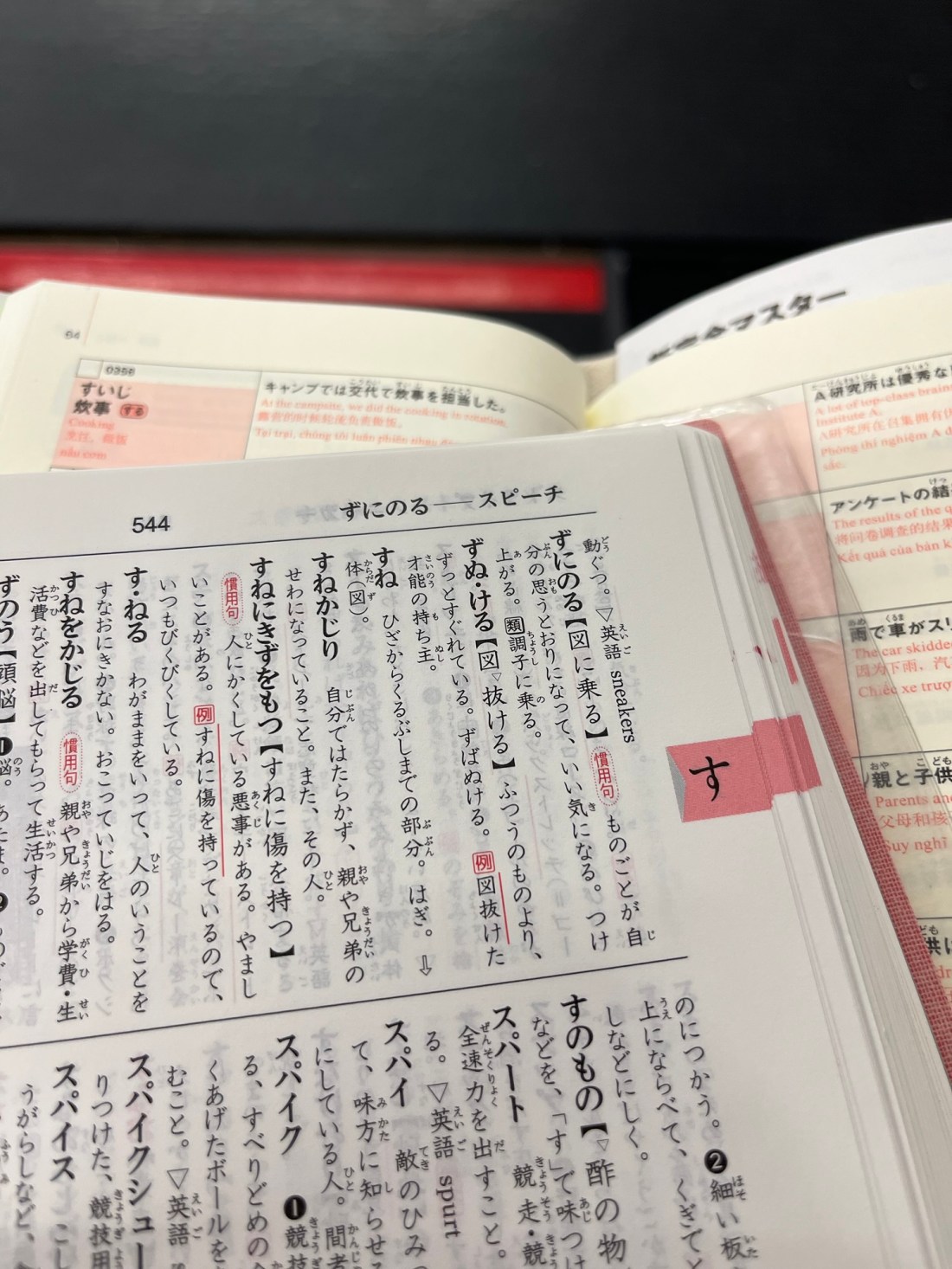

I, on the other hand, have two books open and cramming vocabulary (photo above). This has been my life for the past five or six months.

Why? Because I am going to take the JLPT certification exam this year?

“Again?!” you might be thinking. “Didn’t you bomb the last exam?”

Well, yes. Yes I did. 😅

I spent a lot of time reflecting why I failed so badly, and the basic problem is vocabulary. I just don’t know enough.

I can read Japanese, and often do, but I rely on dictionaries too much, which slows things down, and makes it hard to just enjoy a book. It’s also disruptive to comprehending the sentence.

The problem is is that a language, any language, has tens of thousands of words. A native speaker intuitively knows most of them, but a foreigner has to catch up and learn them too. They’ll never quite know as much as a native speaker, but knowing a lot of words helps reach a “critical mass” where you can function in that language and learn the rest later.

But how many words are needed for critical mass?

A very rough guess is maybe 10,000 words, enough to be a functional adult living and working in that society. Maybe 20,000? I am not sure. Many of these words are grade-school level vocabulary, btw. You might be surprised by how much a child knows by the fifth grade.

The point is is that if you want to get good at a language you have to invest a lot of time and effort to building your vocabulary. It’s not impossible but it’s both a long-term and large scale effort.

Flash cards are a tried-and-true method, and Anki SRS is a great way to make flash cards. But making good flash cards that are helpful and not a burden is important too.

Previously, I made my flash cards too long, too complicated. I had both “recall” (English to Japanese) and “recognition” (Japanese to English) fields in the same cards, and the sentences were long and took time to read.

This is OK when learning tens of words, but thousands of flash cards like this is really clunky; and review takes forever. As a working parent with little free time, that’s not going to be sustainable.

So, starting in late 2025, I started making smaller, simpler flash cards. For starters, I want to at least recognize (Japanese to English) a word in a sentence, so I stopped adding recall fields. Also, I use very short, simple example sentences that I pull from my textbook and my kids’ dictionaries. If the sentence is too long, I pare it down to the essential part.

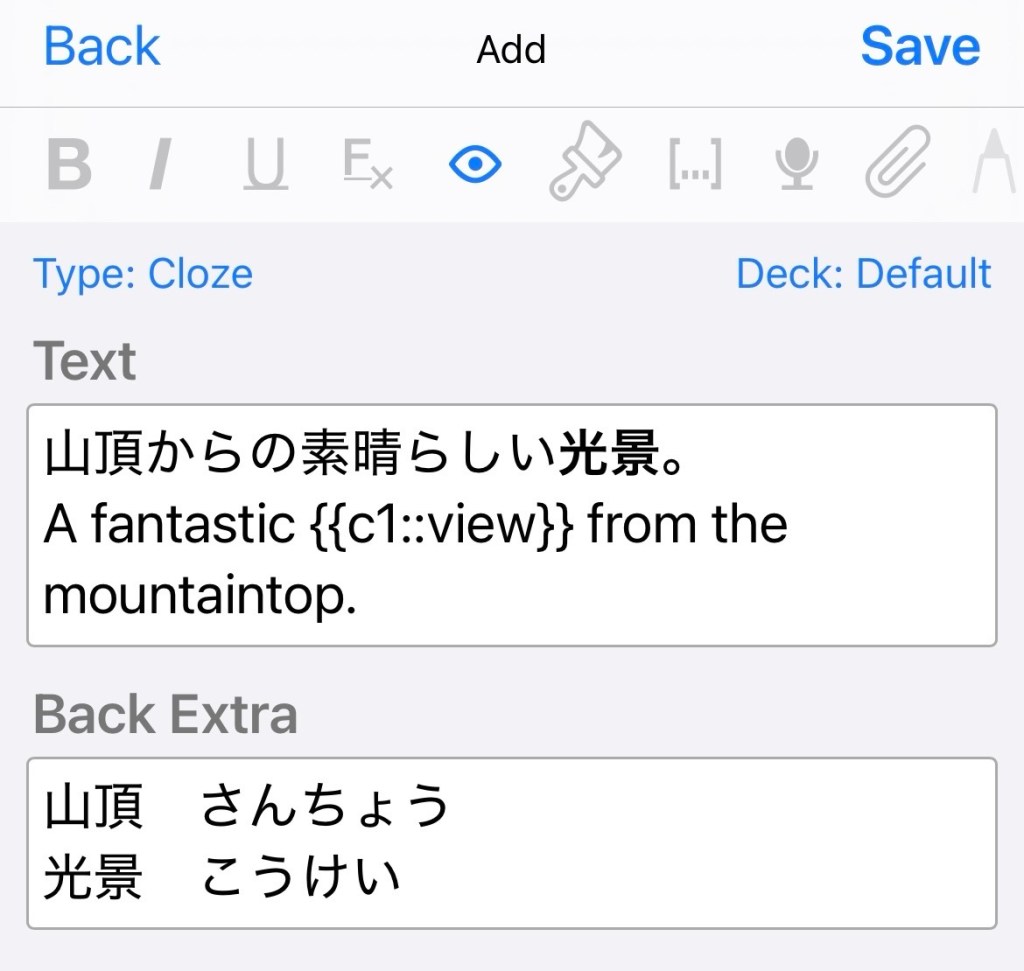

This is an example Cloze-format card I made:

The word I care about is highlighted in bold font, and the English answer, “view”, is below (the Cloze field).

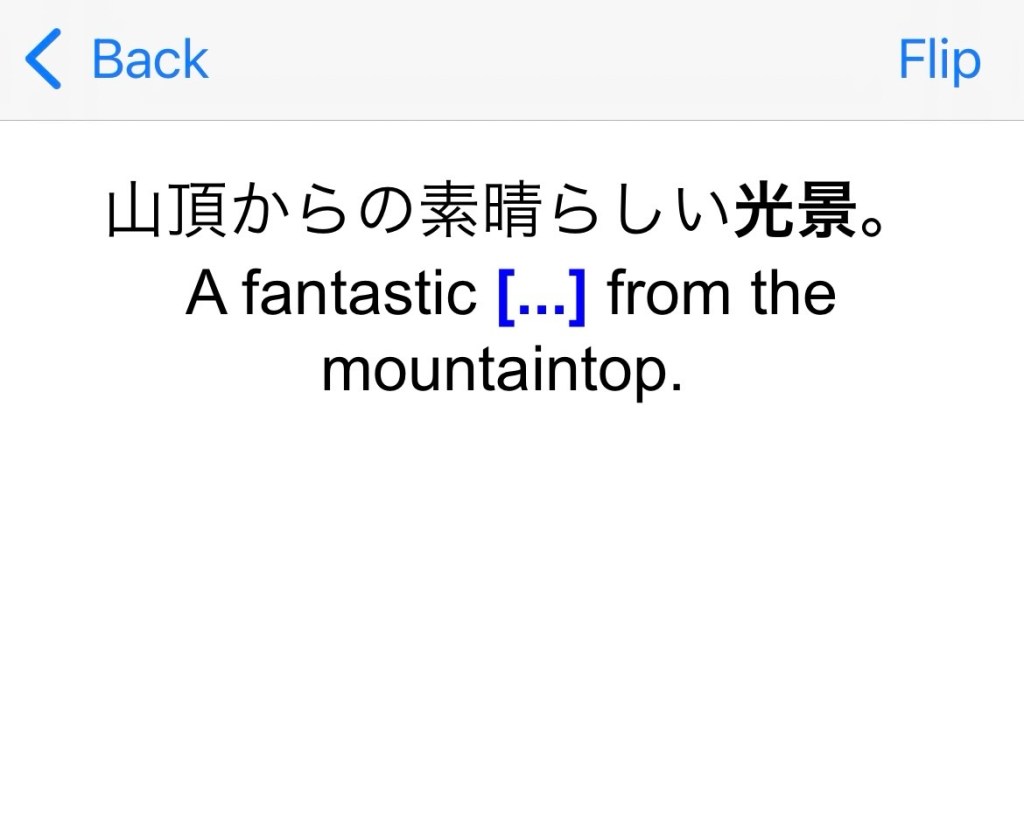

In practice it looks like this :

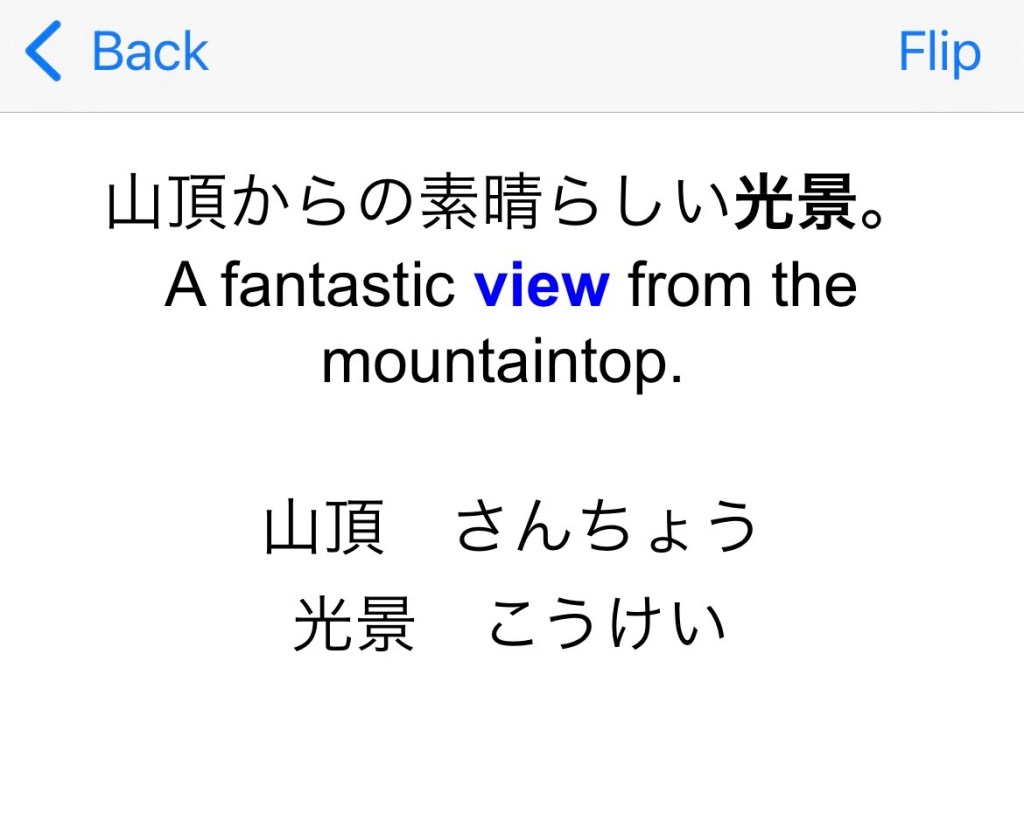

and the answer:

The goal is to make flash cards that you can flip through quickly and easily, but also unambiguous (no mind games), so you can review many cards in one session without getting tired.

If the card is too vague, or too complex, it becomes exhausting to review and you get frustrated.

Also, it really helps to learn a few words a day, not cram many at once. This means less stress, but also better retention in the long-run.

I have also found the Shin Kanzen Master vocabulary books, like this one, pretty helpful for providing a level-appropriate list of words to learn; and a good foundation for making flash cards.

So, is it working? I started this sometime late last year and I have noticed that many of my books are easier to read than before. I can read whole pages without needing a dictionary. And yet, there are times when I still have to use a dictionary if the page has unfamiliar vocabulary.

So, I am happy that I have made progress, but also I have a long ways to go.

And the JLPT exam is only months away….

You must be logged in to post a comment.