Recently, I have been dabbling in learning ancient Greek language for the first time in years. I polished off my old DVD copy of the Greek 101 course from The Great Courses which I bought during the Pandemic after my local library no longer had it available.1 It’s been fun to review old lessons, get reacquainted with such a gorgeous language, and so on.

Anyhow, something I wanted to share was a famous axiom in Koine Greek found throughout the Eastern Roman (a.k.a. the Byzantine) world:

ΝΙΨΟΝΑΝΟΜΗΜΑΤΑΜΗΜΟΝΑΝΟΨΙΝ

(Νίψον ἀνομήματα, μὴ μόναν ὄψιν)“Wash your sins, not only your face.”

This is pronounced as Nipson anomēmata mē monan opsin. This is a famous palindrome (same forwards or backwards) that according to Wikipedia is attributed to one Saint Gregory of Nazianzus. I am not super familiar with the Orthodox tradition, but feel free to consult Wikipedia for more details. You can find it at many monasteries across the Eastern Roman world, including the holy font at the Hagia Sophia, the central church of Constantinople.

In any case, the concept of ablution is also found in Buddhism and expresses a similar sentiment.

Buddhism has a popular custom whereby one performs some kind of ablution with water or incense before approaching a Buddhist altar to pray. It is not strictly required, but is commonly performed as a gesture of respect toward the Buddhist deity you are visiting by cleansing oneself at a superficial level. Within Japanese Buddhism, some sects encourage this more than others; from what I have learned Tendai Buddhism tends to emphasize this a lot, Pure Land Buddhist sects (e.g. Jodo Shu and Jodo Shinshu) do not. The emphasis varies, in other words.

But also ablution in Buddhism is not limited to the external ritual; we also the concept of repentance (e.g. “washing the soul”). This is not the same thing as Western religions, where someone begs God for forgiveness for transgressions committed. Instead, the Buddha strongly encouraged us to constantly evaluate our past conduct, and use the Dharma as a kind of yard-stick to measure them: were they skillful actions, or unskillful actions? Inevitably, one must confront their own unskillful actions. We all do. It is part of being a human being.

So, in Buddhism, many traditions have a ritual were people reflect on their past actions and renounce them, resolving to do better. It is encouraged to do this in front of a statue of the Buddha, and to repeat the liturgy out loud, not just in one’s mind:

All of the misdeeds I’ve committed in the past, are the result of my own greed [or craving], anger and delusion [or ignorance]. I renounce [or repent] these misdeeds.

Translations vary by community, this is just one example.

The idea is that by acknowledging and confessing one’s faults, one not only learns from one’s mistakes, one also potentially diminishes some negative karma that one has sown, and also prevents further self-harm (i.e. guilt, self-recrimination) by letting go and forgiving oneself.

So, just as the old Greek palindrome says, Buddhist practice is not only washing one’s face, but also one’s “soul”.2

Namu Shakamuni Nyorai

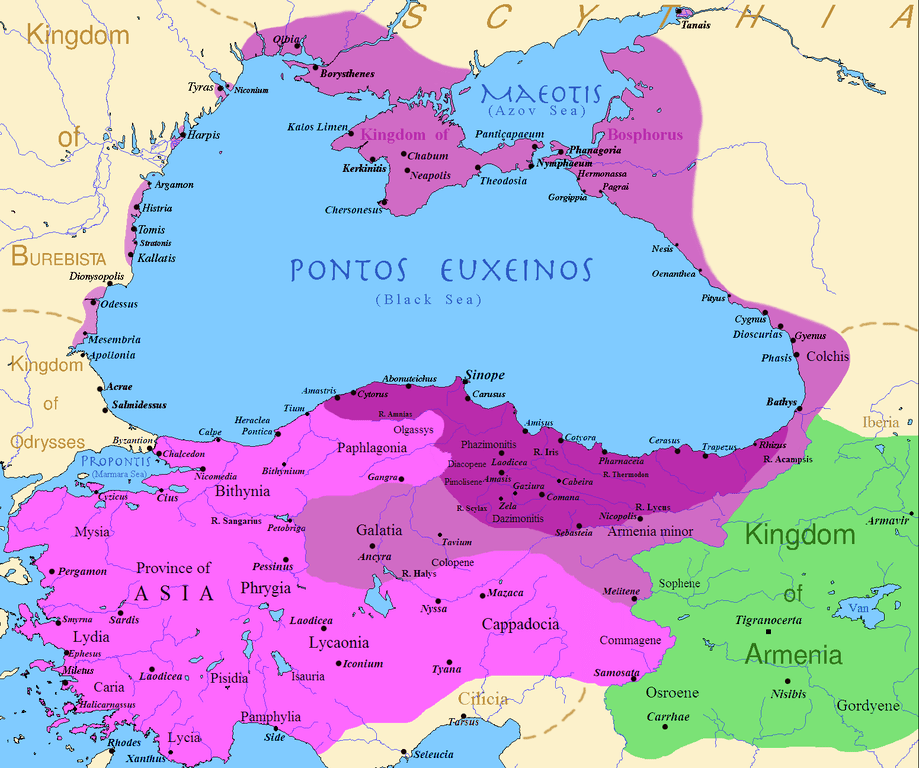

P.S. A common misunderstanding is the primary language in the Roman Empire was Latin. In fact, most of the population spoke Greek as their primary language, though this varied widely by region. This prevalence of Greek was both a leftover from the Hellenistic Age, but also because even Romans felt that Greek was a prestige language, and wealthy Romans hired Greek tutors for their children when possible. Julius Caesar’s famous “Et Tu Brute” quote was actually recited in Greek (Kai Su Teknon).

1 I prefer having hard copies of things, whenever possible.

2 Buddhism is somewhat unique among world religions in that it teaches the concept of “no-soul” (anatman), so by “soul” I don’t mean a literal soul, but the mind and one’s provisional self.

You must be logged in to post a comment.