My family and I visit a certain Shingon-sect Buddhist temple in the area for New Years tradition, and also for Setsubun rituals (namely mamemaki bean-throwing, plus good luck). Neither my wife nor I follow the Shingon sect, but Japanese-buddhist temples for the Japanese community (not Westerners) are rare, so we are glad to visit despite the lengthy drive.

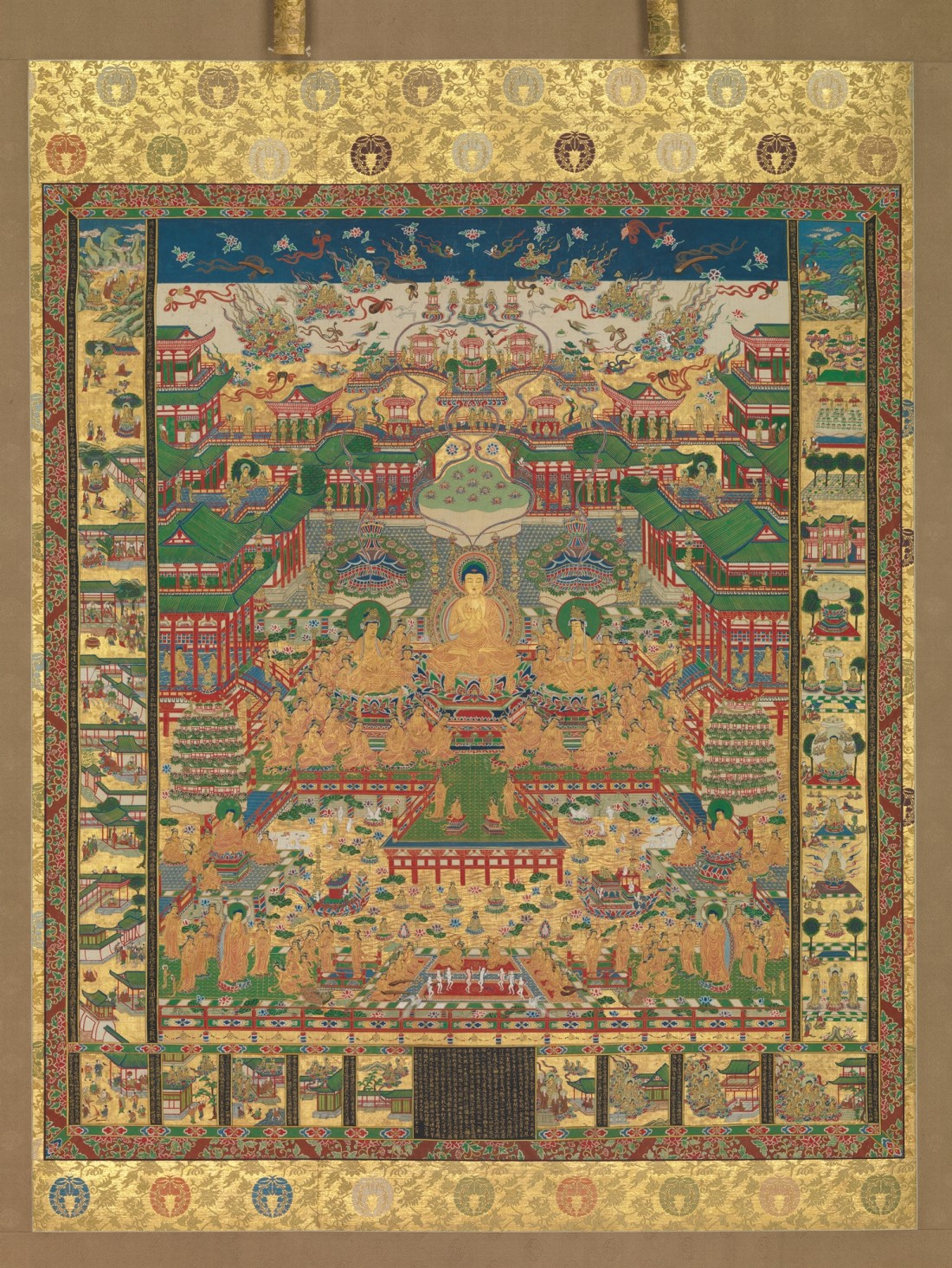

Shingon Buddhism, one of two “esoteric” (mikkyō, 密教) Buddhist traditions in Japan,1 relies on a complex array of ceremonies, rituals, symbolism, and mantra chants that help awaken one’s Buddha-nature not through words, but through a kind of non-verbal impact. This requires a trained teacher to guide one through it, hence it’s called “esoteric” Buddhism (a.k.a. Vajrayana Buddhism). Years ago, I attended a “moon meditation” sitting once where each one of us sat and meditated before a hanging scroll showing a full moon. It was an interesting experience.

Anyhow, one ceremony that’s very common in Shingon is called the Goma-taki (護摩炊き) ritual, or “fire ceremony”. This is often called Goma in English. This is a video provided by Koyasan Temple in Japan which shows a complete ceremony: a priest creates a pyre within a sacred space, often before a statue of Fudo-myo-o (不動明王). Throughout the ceremony, the priest recites certain chants and uses certain hand-gestures. The fire is thought to purify one’s mental defilements, burn away past karma too, and also certain sticks are added to the fire with people’s aspirations and wishes written on them.

At our temple here locally, the priest conducts the Goma ritual as well, and people receive blessings from the ceremony one by one, and we also receive small o-fuda talisman that we place next to our Buddhist altar at home for protection. These are larger than omamori charms, made of wood or cardboard, and usually enshrined, not carried on your person.

The origins of the Goma-taki ritual are taken from Indian religious practices of the past, but gradually underwent “Buddhification” (absorbing practices, and making them Buddhist) and this is why, I believe, that esoteric Buddhism arose in later generations of Buddhism in India.2 The deities portrayed in esoteric Buddhism also have origins in India, but transformed as they were brought through China to Japan.

Goma-taki rituals are frequently held for the public in larger Japanese temples, so you can easily drop and just observe, but be aware they can take up to an hour or more. But it is a pretty interesting experience and well worth observing.

Namu Daishi Henjo Kongo

(Praise to the Great Teacher Vairocana Vajra, a.k.a. Kukai / Kobo Daishi)3

1 the other is Tendai Buddhism, which calls it taimitsu (台密), not mikkyo. What are the differences? Not sure. Both lineages come from the same Chinese-Buddhist tradition of the time, but beyond that, no idea.

2 Seen from one perspective, the earliest texts and traditions in Buddhism did not feature any esoteric practices and rituals, so if you’re looking for “pristine” Buddhism then esoteric practices don’t fit this. From another point of view, Buddhism continued to innovate across generations, first Mahayana Buddhism, then esoteric practices, so in that light esoteric Buddhism solves problems of practice and teaching that earlier Buddhism struggled with. I don’t know which viewpoint is the right one, personally. I am a big proponent of easy, accessible Buddhist teachings and practices (hence the nembutsu, precepts, etc), and esoteric Buddhism doesn’t make this easy. And yet, it is surprisingly popular in Japan (2nd only to Pure Land Buddhism), so maybe there’s something there that I’ve failed to notice all this time? 🤷🏼♂️

3 This is often recited in Shingon tradition the way namu amida butsu is recited in Pure Land traditions in Japan.

You must be logged in to post a comment.