I had an idea recently while flipping through my book on the journeys of the Buddhist monk Xuan-zang (pronounced like “Shwan-tsong”). Xuan-zang was the famous Buddhist monk who walked to India in order to bring back more information and texts in order to help develop Buddhism in his native China. In my old post, I covered some of the trials and tribulations of this amazing journey, and even made a fun song. However, looking back the post felt incomplete. I realized that many of these places that Xuan-zang traversed are obscure and forgotten now despite their central importance to Buddhist history, and the journey was so long that it’s too much to really explore in a single post.

So, this is the start of a series of posts meant to help retrace Xuan-zang’s journey, explore places of significance and how they tied into larger history. I don’t have a schedule yet (these posts take a while to write), but I am working on the next few drafts already.

Today’s post is the prologue episode, covering China at this time, and why Xuan-zang left.

Quick note: because this episode in particular uses a lot of Chinese names, for the sake of accuracy and modern readers, I am using the pinyin-style accent marks where relevant, and also using Simplified Chinese characters. I also put in lots of hyphens to help with pronunciation.

The Tang Dynasty

Chinese history, until the Republican era (1912 onward) had seen a series of kingships followed by imperial dynasties. Although, we usually call the country “China”, the name used by Chinese people in antiquity, and by their neighbors, was often taken from the current ruling dynasty.

Dynasties came and went. Some were fairly short-lived such as the Sui, others were incredibly powerful and long-lasting such as the Ming. Some were constantly fighting for their existence, such as the Song, others were fractured into a series of “mini-dynasties” that only exerted control over a region and were unable to unify China.

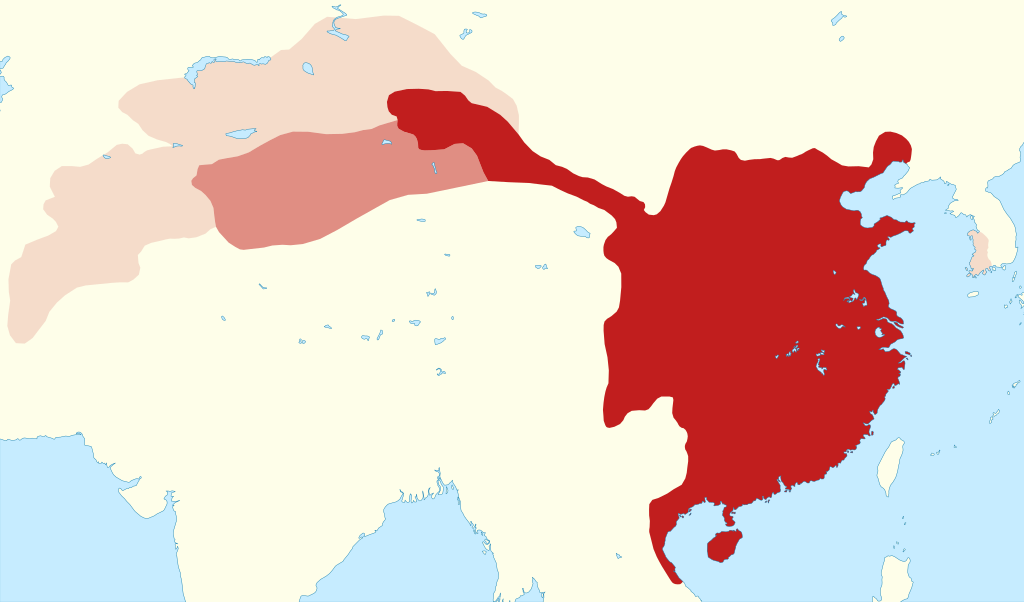

Xuan-zang lived during the last days of the Suí Dynasty, and the early days of the Táng Dynasty (唐). “Great Tang” (大唐) as it called itself, lasted from 618 – 907, and was one of the high points of Chinese civilization. The empire expanded very far to the west, along the Silk Road (more on that in future posts) and actively imported all kinds of art, people, ideas, religions and material culture from Central Asia. Compared to earlier dynasties, Great Tang was much more cosmopolitan and less insular.

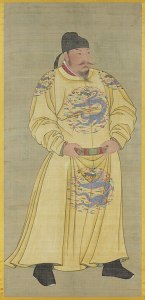

Xuan-zang lived primarily during the reign of the second Tang emperor Tài-zōng (太宗), who was an incredibly powerful, dynamic ruler. Chinese history still reveres him as of the greatest rulers. Tai-zong aided his father, the first emperor, in overthrowing the previous dynasty. Further, he was a powerful, expansionist ruler with a strong sense of administration, which helped provide stable foundations for Great Tang.

The Capital of Chang-An

The capital of Great Tang was the city of Cháng-ān (长安) in the western part of China. The city was a massive, cosmopolitan center of administration, commerce and culture. Chang-an at its height grew to 30 square miles, which was massive compared to Rome which occupied only 5.2 square miles. The population by 742 was recorded as 2,000,000 residents and of these 5,000 foreigners.

Chang-an was easily one of the world’s greatest cities at the time, and it had a great influence on its neighbors as well: the layout for the capital of Japan, Kyoto, was intended to resemble Chang-an, and great Buddhist masters such as Saicho’s rival, Kukai, studied there extensively. It was here that many Buddhist texts that came from the Silk Road were translated here as well.

Other religions, such as Nestorian Christianity, Zoroastrianism, Manichaeism and even Judaism and Islam all had a presence in Chang-an.

As the easternmost point of the Silk Road, it was here that many journeys began or ended…

Buddhism in Great Tang

The Tang Dynasty is often regarded as one of the high points of Chinese civilization, but also for Buddhism. Buddhism had emerged in China centuries earlier but its spread was slow at first. The native Confucian community particular resented the foreign Buddhist teachings as un-filial, unproductive (since monks did not work fields), and a drain on national resources.

In spite of the criticisms, it spread nonetheless. Wave and wave of teachings, newly translated texts, and schools of thought were imported from the Silk Road, allowing Buddhism to gradually take root, articulate its teachings better over successive generations, and develop natively Chinese schools of thought such as Tiān-tāi, Huá-yán, and Pure Land alongside imported schools of thought from India such as Fǎ-xiàng (Yogacara) and Sān-lùn (Madhyamika). By the time of the Tang Dynasty, massive temple complexes had arisen around Chang-an and other major cities.

This was a rare time when there was still a connection between Buddhist India and China, allowing a free flow of information. Later, when Buddhism fell in India, and the Silk Road was no longer safe to travel due to warfare, China was cut off.

Emperor Tai-zong himself had a distant relationship with Buddhism in his early reign. He kept it at arm’s length and strictly regulated. Further, travel in and out of China was tightly restricted, so that while there was commerce and trade, one could only do so with official permissions. More on this shortly.

Enter Xuan-Zang

Xuan-zang was the second son of his family. His older brother had ordained as a Buddhist monk, and Xuan-zang decided to follow in his footsteps at a young age. During the collapse of the Sui Dynasty, both brothers came to Chang-an where it was safe, and undertook further Buddhist studies. Since Xuan-zang proved to be a promising student, he was soon given access to advanced Buddhist texts and eventually ordained as a full monk in 622.

As to why Xuan-zang decided to journey all the way back to India, he is quoted as stating the following:

The purpose of my journey is not to obtain personal offerings. It is because I regretted, in my country, the Buddhist doctrine was imperfect and the scriptures were incomplete. Having many doubts, I wish to go and find out the truth, and so I decided to travel to the West at the risk of my life in order to seek for the teachings of which I have not yet heard, so that the Dew of the Mahayana sutras would have not only been sprinkled at Kapilavastu, but the sublime truth may also be known in the eastern country.

During his studies, Xuan-zang had noticed copyist errors, corruptions of texts, missing texts and other textual issues that prevented a thorough understanding. Thus, he resolved to journey to India, much like a monk named Fa-xian (法显) had done centuries earlier. He was particularly interested in the writings of Vasubandhu and his half-brother Asanga , who were crucial to the development of Mahayana Buddhism as we know it. Xuan-zang and some like-minded monks petitioned the Emperor Tai-zong to be allowed to journey to India, but never received an answer. He made his preparations, possibly learning some Tokharian language (commonly spoken along the Silk Road at that time) from the foreign quarters at Chang-an, then went west.

By the time Xuan-zang reached the Yumen Pass (Yùmén Guān 玉门关) at the western end of Great Tang, he had attracted some unwanted scrutiny by authorities, and wasn’t permitted to leave. By this point, his companions had lost their nerve, but Xuan-zang was determined to continue. With some help from a sympathizer, Xuan-zang defied imperial orders and snuck around the Yumen Pass to leave China. He was now a criminal, and he was alone with a vast desert ahead of him.

What happened next? Find out in next episode.

You must be logged in to post a comment.